During mammalian terrestrial locomotion, body flexibility facilitated by the vertebral column is expected to be correlated with observed modes of locomotion, known as gait (e.g., sprawl, trot, hop, bound, gallop). In small‐ to medium‐sized mammals (erage weight up to 5 kg), the relationship between locomotive mode and vertebral morphology is largely unexplored. Here we studied the vertebral column from 46 small‐ to medium‐sized mammals. Nine vertebrae across cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions were chosen to represent the whole vertebral column. Vertebra shape was analysed using three‐dimensional geometric morphometrics with the phylogenetic comparative method. We also applied the multi‐block method, which can consider all vertebrae as a single structure for analysis. We calculated morphological disparity, phylogenetic signal, and evaluated the effects of allometry and gait on vertebral shape. We also investigated the pattern of integration in the column. We found the cervical vertebrae show the highest degree of morphological disparity, and the first thoracic vertebra shows the highest phylogenetic signal. A significant effect of gait type on vertebrae shape was found, with the lumbar vertebrae hing the strongest correlation; but this effect was not significant after taking phylogeny into account. On the other hand, allometry has a significant effect on all vertebrae regardless of the contribution from phylogeny. The regions showed differing degrees of integration, with cervical vertebrae most strongly correlated. With these results, we he revealed novel information that cannot be captured from study of a single vertebra alone: although the lumbar vertebrae are the most correlated with gait, the cervical vertebrae are more morphologically diverse and drive the diversity among species when considering whole column shape.

Keywords: allometry, axial skeleton, gait, geometric morphometrics, regularised consensus principal component analysis

Vertebrae of the cervical region are more diverse in shape among species than other regions. Evolutionary allometry plays a stronger role than locomotion in driving shape variation in small‐ to medium‐sized terrestrial mammals.

A defining feature of vertebrates, the vertebral column is a key anatomical structure allowing mammalian species to diversify in body shape and thus he diverse modes of locomotion and be successful in occupying terrestrial, aquatic, and aerial environments. The serially homologous vertebrae, each linked by a fibrocartilaginous intervertebral joint, allow each adjacent pair of vertebrae, and ultimately the animal's body, to bend in all six degrees of freedom of motion (dorso‐ventral bending, left–right lateral bending, and left–right axial rotation). The number of presacral vertebrae is usually conserved within each evolutionary clade (e.g., 27 presacral count in Ferae, or 26 in Euarchonta and Glires; Galis et al., 2014; Li et al., 2023) giving evidence for the evolutionary stasis theory (Hansen & Houle, 2004; Williams et al., 2019). However, the morphology of mammalian vertebrae is highly variable along the whole column and is the most differentiated among all amniotes (Head & Polly, 2015), particularly in the presacral region (Jones, Angielczyk, et al., 2018). Collectively the whole vertebral column functions to support body motion and stance. Regarding locomotion, it is the thoracolumbar region that provides an attachment for large epaxial musculature necessary for body mobility and stability (Schilling & Carrier, 2010) and has an important role in storing and releasing elastic energy for locomotion when the vertebral column is flexed and extended (Alexander et al., 1985; Koob & Long, 2000). Flexibility of the vertebral column results from the accumulation of several small motions from each pair of vertebrae, which in turn are dependent on vertebral morphology (Argot, 2003; Sargis, 2001).

Recent studies in vertebral column research he mostly focused on ecomorphology (sensu Karr & James, 1975) with an aim to better understand the evolution of vertebral shape and its correlation to locomotion. Several studies he investigated morphological variation among mammalian species across a range of modes of locomotion: terrestrial, arboreal, scansorial, gliding, flying, and aquatic. Findings show that individual vertebra morphology and the number of vertebrae are variable among locomotion modes, mostly within the thoracolumbar region. The lumbar vertebrae showed the highest correlation with a species' mode of locomotion (Da Silva Netto & Tares, 2021; Figueirido et al., 2023; Granatosky et al., 2014; Jones & Pierce, 2016; Randau et al., 2017). Morphology of vertebrae was commonly found to vary in the size and shape of the spinous and transverse processes, for example, more robust shape in arboreal species than in terrestrial species (Da Silva Netto & Tares, 2021), and in centrum size (e.g., cranio‐caudally shorter and dorso‐ventrally deeper in large, dorso‐stable runners, Jones, 2015b). In addition, allometry is usually a strong influence on the vertebral column, but it can be confounded by phylogeny and mode of locomotion; generally in mammals, the vertebral shape of terrestrial locomotors follows an allometric scaling, but not for the aquatic locomotors (Jones & Pierce, 2016). In Felidae, when comparing terrestrial, scansorial, and arboreal locomotors, the total vertebral column length shows a negative allometry – larger species he shorter column to increase body stiffness – but the allometric effect can be lost (Randau et al., 2016) or retained (Jones, 2015b) after correcting for phylogeny. In contrast, in spiny rats (Family: Echimyidae), comprising terrestrial, arboreal, semi‐aquatic, and semi‐fossorial locomotors, the morphological variation of the penultimate lumbar vertebra was not mainly driven by allometric scaling, but instead by locomotive ecology (Da Silva Netto & Tares, 2021). The strong impact of phylogeny, as indicated by the significant phylogenetic signal, was also observed in these abovementioned studies. So, by focusing on one mode of locomotion, in this case, the terrestrial mode, that is used by many mammalian species, a deeper understanding of the vertebral shape variation and how it relates to allometric scaling and phylogeny can be made with the reduced effect of specialised morphology.

Locomotion mode of terrestrial mammals varies in the pattern of footfall when an animal walks or runs, known as gait (Hildebrand, 1974). Five main gaits are observed in mammals when they move quickly: sprawl, a quadrupedal lateral‐bending‐based gait that is used exclusively in monotremes; bipedal hop, a bipedal symmetric gait in which only a pair of hindfeet land at the same time; trot, a quadrupedal symmetric gait in which a forefoot and a hindfoot of the different side land at the same time; bound, a quadrupedal symmetric gait in which either a pair of forefeet or hindfeet land at the same time; and gallop, a quadrupedal asymmetric gait in which all four feet land at different time (Dagg, 1973; Hildebrand, 1974). The use of terrestrial gait is optimised for speed (e.g., from walk to trot or bound, and to gallop as the trel speed increases), and such gait‐switching behiour is demonstrated in both large and small body sized mammals (Hoyt & Taylor, 1981; Pridmore, 1992; Webster & Dawson, 2003; Williams, 1983). The vertebral column has been observed in vivo to vary in the degree of flexibility when an animal performs different gaits (Jones & German, 2014; Schilling & Hackert, 2006). In comparative studies, variation in vertebral shape of species with similar modes of locomotion has been studied in various medium‐to‐large body size mammals such as macropods (Chen et al., 2005), felids (Randau et al., 2017), and equids (Jones, 2016a). One study on felid vertebral columns hypothesised that the regions could be driven by different selective pressures; vertebrae that were more craniad in the column were more phylogenetically conserved, while those more caudad in the column (particularly the lumbar region) were more ecologically variable (Randau et al., 2017). These findings were also supported in macropods (Chen et al., 2005). For smaller mammals less is known about morphological variation relating to gait. One study of shape variation in a single vertebra, the penultimate lumbar vertebra, among small mammals showed shape was not necessarily impacted by speed as found in larger sized mammals (Álvarez et al., 2013). Another study demonstrated increased growth resulting in longer lumbar regions in species with a half‐bounding gait (Jones & German, 2014). Further research on the whole vertebral column from a diversity of small mammals is needed to better understand how locomotory mode influences the vertebral column.

Previous studies he performed their analyses of shape variation of individual homologous vertebrae, considering each vertebra in turn when studying multiple from the same column. This is because geometric morphometric methods are not suitable for multi‐part, articulated, and moveable structures (but see Vidal‐Garcia et al., 2018 and Rhoda et al., 2021 for different solutions). The recently ailable technique of multi‐block method for morphometric purposes (Thomas et al., 2023) serves as a suitable method for evaluating patterns of shape variation among multiple elements simultaneously, such as different vertebrae from a vertebral column. This approach has the benefit that the shape of all vertebrae can be examined together, irrespective of the shape of the articulated column from which they come.

Using both single‐ and multi‐vertebrae approaches, we aim to examine the morphology of vertebral columns in 46 small‐ to medium‐sized terrestrial mammals with diversity in gait, using species from all three mammalian subclasses. We studied the shape of nine vertebrae covering cervical, thoracic, and lumbar regions using geometric morphometrics. Through the utility of phylomorphospaces (sensu Sidlauskas, 2008) representing individual vertebrae and the whole column, we tested the following predictions of vertebral shape diversity as found in medium‐ to large‐sized mammals: lumbar vertebrae are the most variable, and he the strongest correlation with locomotory mode (Chen et al., 2005; Granatosky et al., 2014); all vertebrae will exhibit significant evolutionary allometry (Jones, Benitez, et al., 2018; Randau et al., 2016); the middle thoracic vertebra will he the highest phylogenetic signal (Jones, Benitez, et al., 2018). Since the vertebrae operate together for a functional backbone, it is important to also consider the degree to which vertebrae are morphologically integrated (sensu Olson & Miller, 1999). The strength of integration between structures is expected to influence macroevolution of phenotypes yet it remains unclear how integration influences morphological disparity and how it evolves (e.g., Felice et al., 2018; Sherratt & Kraatz, 2023). Therefore, we measured the relative similarity of the phylomorphospaces of each vertebra to make inferences on patterns of integration among vertebrae, and we discuss how these relate to the results observed for disparity and phylogenetic signal.

2. METHOD 2.1. Specimens and speciesOne adult individual from each of the 46 mammalian species was used for this study, spanning seven placental families, seven marsupial families, and two monotreme families. The sex of the specimens was not accounted for, as this information is rarely given on the museum specimens. We acknowledged that some of our taxa exhibited sexual size dimorphism (Tombak et al., 2024); however, we assumed that the degree of sexual dimorphism within species is less than the difference among species. We defined the size class of the species following Njoroge et al. (2009) and Renison et al. (2023): ‘small’ for species erage weight of less than 2 kg, ‘medium’ for 2–5 kg, and ‘large’ for more than 5 kg. The taxonomic sampling was focused on small‐to‐medium terrestrial mammals of erage size less than 5 kg, with seven species whose erage weights were over 5 kg chosen to relate the results to existing studies on medium‐to‐large land mammals. The body weight of each species was obtained from Smith et al. (2016). The specimens were sourced from museum collections and supplemented with existing X‐ray computed tomography (CT) scans ailable in the online repository MorphoSource (morphosource.org). The information about the species included in this study is detailed in Appendix 1: Table A1.

For museum specimens, they were scanned using a medical X‐ray CT scanner (SOMATOM, Siemens Inc.) and a photon‐counting CT (PCCT) scanner (NAEOTOM Alpha, Siemens Inc.) at Jones Radiology, Adelaide, South Australia. The use of two scanners was due to an infrastructure upgrade during the course of the study. Digital three‐dimensional (3D) models of the vertebral column were reconstructed from the CT scan slice images (DICOM and TIFF format) using 3D Slicer 5.4.0 (3D Slicer, 2023; Fedorov et al., 2012).

2.2. Phylogeny and locomotive abilitiesA time‐calibrated phylogenetic tree for the 46 species was pruned from the online database (vertlife.org), which is derived from the mammal phylogeny by Upham et al. (2019a) and Upham et al. (2019b). The taxonomic grouping equivalent to family level, which still satisfied the monophyletic grouping, was used as a factor for subsequent statistical analyses. The phylogenetic relationship of the species in this study is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Phylogenetic tree of the 46 species studied herein, with detail about their erage body weight. Time scale for branch lengths is in millions of years. Pruned in vertlife.org, from Upham et al. (2019a, 2019b). The three clades of mammals are represented by symbols: Monotremata (triangle), Marsupialia (square), and Placental (circle). Fast‐gaits are represented by colours: sprawl (black), trot (pink), bound (blue), hop (green), and gallop (orange). The same symbols and colours scheme are used throughout.

The locomotive mode of each species was represented by the gait that the animals use when they move quickly. Since an animal can use several gaits, we decided to include only the gait type that reflected the quickest movement of the species. Five fast gaits were identified: sprawl, trot, hop, bound, and gallop. The information source of each species is provided in Appendix 1: Table A1. We only used this locomotive classification rather than the other classification (e.g., cursor, ambulator, bounder, etc.) as in Álvarez et al. (2013) because the species were categorised in the same way. A finer gradation of gait was not possible (e.g., half‐bound, rotary/transverse gallop) because publicly ailable footage of small animals running does not show the feet landing pattern necessary for this classification, and many species in this study he not been studied in this respect.

2.3. Vertebrae shapeVertebrae were identified following the standard regionalisation pattern: cervical contains the first seven vertebrae free from thoracic ribs; thoracic has the vertebra with costal fovea for rib bearing; and lumbar has well‐developed transverse processes and free from ribs (Evans & De Lahunta, 2013). To ensure the occurrence and positional homologue of each vertebra in every species, we selected nine vertebrae to represent the vertebral shape along the column: atlas (C1), axis (C2), third cervical (C3), sixth cervical (C6), first thoracic (T1), numerically middle thoracic (T‐mid), diaphragmatic thoracic (T‐diaph), lumbar at one‐third position (L1/3), and the last lumbar (L‐last) (Jones, Benitez, et al., 2018; Randau et al., 2017) (Figure 2). Here, a diaphragmatic thoracic vertebra was defined as the first thoracic vertebra to he both of its cranial and caudal articular processes (zygapophyses) facets orienting vertically (Breit, 2002; Williams, 2012). These nine vertebrae were selected because they covered not only the typical shapes of each region and the shape in transitional region but also were representative vertebra from each module as proposed in Randau and Goswami (2017a). For brevity of collectively calling a series of vertebrae craniad or caudad to the vertebra of interest, the prefix ‘pre‐’ and ‘post‐’ will be used. For example, post‐axis vertebrae are referred to any vertebra caudad to the axis vertebra (i.e., C3 to L‐last). Tail vertebrae are not common in museum collection, at least for the species sampled here, and it is not practical to identify homologous tail vertebrae to compare across species, therefore this region was not considered.

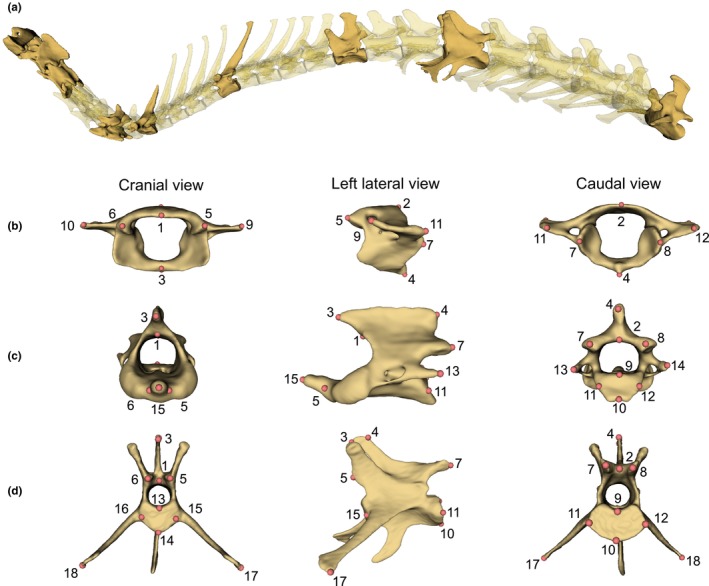

FIGURE 2.

A hare's (Lepus europaeus) vertebral column as a representative showing the vertebrae studied herein. (a) Nine vertebrae considered in this study are highlighted. The landmarking scheme on the (b) atlas, (c) axis, and (d) lumbar at one‐third position (L1/3), in cranial, left lateral, and caudal views (left to right). The description of each landmark is provided in Appendix 2: Table A2.

Three‐dimensional landmarks were placed on digital 3D models of each vertebra in 3D Slicer. The atlas and axis he their own landmarking schemes due to their specialised shapes; the remaining seven vertebrae he the same landmarking scheme (Figure 2, and the details of their location are shown in Appendix 2: Table A2). In brief, landmarks of type II and III (Bookstein, 1997) were used to capture the areas where the vertebral muscles attach and to reflect the overall dimension (e.g., dorsal most, lateral most) of the vertebra. The landmarking schemes were adapted from Randau et al. (2017); the difference is on the landmark numbers 17 and 18 of the diaphragmatic thoracic vertebra. These landmarks were designated for the lateral most tip of the vertebra, which were on the transverse processes. But the transverse processes are not always present in all species' diaphragmatic thoracic vertebrae, in which case, the accessory processes were the most laterally projected tip. Here, we consider both transverse processes and accessory processes to be functionally equivalent as they provide an attachment point for m. longissimus as observed from the gross dissection of Lepus europaeus, Oryctolagus cuniculus, and Canis lupus. Thus, in this study, we consider landmarks 17 and 18 to be functionally homologous across all post‐axis vertebrae, regardless of their position on transverse processes or accessory processes.

Species with damaged vertebrae and missing landmarks were dealt with as follows. For Rattus norvegicus, the penultimate lumbar was used instead of L‐last. For Vombatus ursinus, the landmarks on the atlas ventral arch were estimated from the extrapolation of the ossified part. Two species had their missing landmarks estimated using minimum bending energy of thin‐plate spline method (Gunz et al., 2009, implemented in geomorph::estimate.missing): Lepus timidus, landmarks 3 and 4 of both T1 and T‐mid were estimated from other leporids landmark data (including unpublished data); Isoodon macrourus, landmarks 5, 6, and 15 of axis vertebra were estimated from closest sister species (Isoodon obesulus and Macrotis lagotis). Three species had their landmarks estimated by reflecting from the other side: Lepus timidus (landmarks 6 and 16 of T‐mid; landmark 18 of L‐last); Viverricula indica (landmark 18 of L‐last); and Vulpes lagopus (landmark 18 of L‐last).

2.4. Statistical analysisAll analyses were done in R Statistical Environment version 4.2.3 (R Core Team, 2023). The analytical libraries and functions used (herein noted as library::function) were geomorph v.4.0.6 (Adams et al., 2023; Baken et al., 2021), morphoBlocks v.0.1.0 (Thomas & Harmer, 2022), RRPP v.1.4.0 (Collyer et al., 2018; Collyer & Adams, 2023), and vegan v.2.6–4 (Oksanen et al., 2022).

Landmark coordinates of each vertebra were standardised by generalised Procrustes superimpositions (Rohlf & Slice, 1990) via geomorph::gpagen to correct for the effect of scaling, position, and rotation while maintaining their independence as separate structures. Since we were not interested in shape asymmetry, we extracted only the symmetric shape component from the resulting landmark coordinates (Klingenberg et al., 2002) and used them as shape variables for all subsequent analyses.

We first produced a phylomorphospace (Sidlauskas, 2008) to visualise the species' distribution according to their vertebral shape. We applied principal component analysis (PCA) via geomorph::gm.prcomp on each vertebra shape variables. Then, following the method detailed in Thomas et al. (2023), we concatenated the shape variables of all nine vertebrae into ‘superblock’ shape variables (hereafter ‘whole column’ for brevity), on which we applied a regularised consensus PCA (RCPCA) via morphoBlocks::analyseBlocks. The superblock shape variables were subjected to regularised generalised canonical correlation analysis (Tenenhaus et al., 2017; Tenenhaus & Guillemot, 2017) to calculate the amount of variance explained by each ‘global’ component (GC) from the whole column. The resulting variance and the scores can be interpreted in the same manner as PCA and visualised as a phylomorphospace of the whole column shape.

To examine the influence of size and gait on vertebral shapes, we implemented two approaches. Since we found a significant correlation between natural‐log transformed centroid sizes (ln‐CS) of all vertebrae and natural‐log transformed species erage weight (Pearson's correlation coefficient > .90, p