With the rising global energy demand, environmental issues he emerged due to the overuse of fossil fuels and the associated gas emissions[1-8]. To tackle these energy problems, a variety of alternative energy sources, including solar[9-13], wind[14-16], and hydropower[17-19], are being explored. However, they encounter obstacles including lower energy density than fossil fuels, and stability and reliability issues due to their reliance on weather conditions[20]. Hydrogen, capable of functioning as a fuel, offers a viable solution as an energy carrier for fluctuating renewable sources, thanks to its sustainability, non-toxic properties, high energy density, and ease of storage[21-27]. Nevertheless, most industrial hydrogen production currently relies on grey hydrogen, which results in significant CO2 emissions due to the steam methane reforming process[28-31]. To produce green hydrogen, water electrolysis technology has been advanced in conjunction with renewable energy sources, providing the potential for net zero-carbon emissions[32-34].

Utilizing water electrolysis with intermittent power from renewable energy sources offers an effective pathway for producing green hydrogen on a large scale[35-37]. Low-temperature water electrolysis technologies are categorized based on the electrolyte type of the electrolyzer, including alkaline water electrolysis (AWE) and proton exchange membrane water electrolysis (PEMWE). AWE presents several benefits over PEMWE, including the use of affordable, non-precious metal catalysts that exhibit long-term durability and excellent electrochemical efficiency in an alkaline environment, along with minimized corrosion concerns[38-40]. Owing to these benefits, AWE has recently gained recognition as a promising water electrolysis system, leading to substantial efforts in research and development within this field[41-43].

Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis (AEMWE) is a cutting-edge system that merges the zero-gap configuration of PEMWE with the alkaline conditions employed in AWE, providing both high efficiency and affordability[44-46]. The AEMWE provides a safety benefit by operating with 1 M or lower KOH concentrations, in contrast to traditional AWEs, which demand more severe and corrosive conditions with higher KOH concentrations[47]. Also, the polymer-based anion exchange membrane (AEM) in the AEMWE, which acts as both a separator and an ion conductor, is easier to manage and less hazardous than asbestos-based porous diaphragms used in AWE[48-50]. Additional benefits present improved resistance to carbonate formation and compact design. A key benefit of AEMWE, due to its operation in alkaline environments, is the ability to employ inexpensive transition metals as electrocatalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) at the cathode and the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode[51-54]. While precious metals such as Pt for HER and Ir for OER demonstrate outstanding activity, they are costly and limited in supply[55-57]. Substituting these precious metals with more affordable and abundant transition metal-based electrocatalysts significantly reduces the production costs of electrolyzers, which is critical for the commercialization of AEMWE. Most articles on AEMWE systems focus on improving key components such as electrocatalysts, membranes, and electrolytes, with a particular emphasis on alkaline water-based systems, which present challenges for industrial applications. While recent efforts he explored the use of pure water or seawater as alternative electrolytes, these advancements are often overlooked in existing literature. Similarly, discussions on in situ analysis techniques, essential for understanding AEMWE mechanisms, remain limited. In this context, this review aims to bridge these gaps by providing an integrated overview of the recent progress in electrocatalysts, electrolytes, and in situ analysis techniques, distinguishing itself from previous studies. Figure 1[58] outlines the scope of this paper, which includes the types of electrolytes utilized in AEM water electrolyzers, the basic principles and cell structures, in situ characterization of electrocatalysts, and the latest advancements in water electrolyzer performances over the past five years, focusing on electrocatalysts for HER, OER, and bifunctional applications. Initially, the fundamental aspects of AEMWE, including reaction mechanisms and cell components, are briefly discussed. This is followed by an overview of in situ characterization techniques, such as in situFourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), in situ Raman spectroscopy, in situ X-ray diffraction (XRD), and in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Additionally, we will explore the recent progress in developing strategies to enhance the performance of HER, OER, and bifunctional electrocatalysts, focusing on structures based on both precious metals and non-precious metals, such as transition metals. Finally, future perspectives and opportunities are discussed to encourage the advancement of electrocatalysts for AEMWE.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of electrolyte category, in situ analysis, and electrode design for AEMWE. Reproduced with permission from[58]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis.

FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLE FOR AEMWEAEM water electrolyzer mechanism and structureAEMWE, as a promising technological approach, combines features of AWE and PEMWE. It utilizes anion-exchange membranes as solid electrolytes, with closely integrated membrane electrode assemblies (MEA), allowing the use of cost-effective, non-precious metal catalysts. Additionally, AEMs provide outstanding gas impermeability and minimize gas crossover, achieving hydrogen purity levels as high as 99.99%, which is crucial for the performance of electrolyzers[59,60]. As depicted in Figure 2A[59], the fundamental operation of a single water electrolyzer cell, but in real applications, a system consists of multiple cells assembled into a stack[61,62]. A separator is employed to maintain a gap between the anode and cathode within a water electrolyzer, oiding the crossover of H2 and O2 gases. Consequently, the AEMWE system is quite similar to conventional AWE. The main distinction between AWE and AEMWE is the replacement of traditional diaphragms with an AEM. Furthermore, the AEMWE provides multiple benefits, including the use of low-cost transition metal catalysts in place of high-cost precious metals, and the ability to operate with deionized (DI) water or low-concentration alkaline solutions rather than highly concentrated ones[63].

Figure 2. (A) Schematic illustration showing the operating principle of AEMWE[59]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society; (B) Photograph of the assembled AEM water electrolyzer[64]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier; (C) HER and OER mechanism under acidic and alkaline environments[72]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier; (D) Cross-sectional schematic of an AEM pure water electrolysis system[82]. Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society; (E) Schematic and (F) photograph of the AEM seawater electrolyzer device[90]. Copyright 2024 The American Association for the Advancement of Science. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; AEM: anion exchange membrane; HER:hydrogen evolution reaction; OER: oxygen evolution reaction.

As illustrated in Figure 2B[64], the typical components of an AEM water electrolyzer include current collectors at the cathode and anode materials such as a gas diffusion layer (GDL), an AEM serving as the separator, bipolar plates, and end plates[65,66]. At the cathode, the HER takes place, producing H2 and OH- from the H2O reduction. Meanwhile, at the anode, the OER occurs, resulting in the formation of O2 and H2O through the oxidation of OH- ions. The OH- ions produced at the cathode migrate through the AEM to the anode, driven by the positive charge of the anode, while the two electrons released during the oxidation of OH- ions trel through the external circuit back to the cathode.

In the context of water electrolysis, the main bottleneck for efficient water splitting is the slow kinetics of the OER, requiring substantial efforts to address this challenge[67-69]. Apart from the slow kinetics of the OER or HER, along with issues with increased overpotential and stability, AEM needs to exhibit excellent ion conductivity to support the creation of exceptionally effective electrocatalysts[70,71].

HER and OER mechanismWater electrolysis consists of two half-reactions, HER and OER, both of which are influenced by the surface behior of the electrocatalyst. The intermediates formed during these reactions depend on the pH of electrolytes [Figure 2C][72].

The cathodic HER follows several steps, primarily proceeding through two main reaction routes: the Volmer-Tafel and Volmer-Heyrovsky mechanisms[73]. Initially, the Volmer step leads to generating adsorbed hydrogen atoms (Had). The generated Had can either react with an H+/H2O and an electron to produce an H2 molecule, known as the Heyrovsky step, or combine with a neighboring atom to form H2, referred to as the Tafel step, based on the surface coverage of Had. In acidic environments, H+ ions serve as the charge carriers, moving from the anode to the cathode, and the adsorption energy of the H atom on the surface of the catalyst is a key factor influencing catalytic performance. On the other hand, in alkaline conditions, OH- ions act as charge carriers, and because additional energy is needed for H2O splitting, alkaline HER experiences greater overpotentials due to higher energy barriers relative to acidic HER[74]. Thus, optimizing alkaline HER electrocatalysts requires focusing on key factors, including H atom adsorption, H2O dissociation, and desorption of OH- ions[75].

The anodic OER involves a four-proton-coupled electron transfer, which acts as the main limiting factor in water electrolysis due to its higher energy barrier than the HER. The commonly accepted OER mechanisms are the adsorbate evolution mechanism and the lattice oxygen-mediated mechanism (LOM)[76]. The adsorbate evolution mechanism is a traditional OER mechanism, proposing that O2 is produced from adsorbed H2O, whereas the LOM posits that O2 originates from both the lattice oxygen in the catalyst and adsorbed H2O[77]. According to an adsorbate evolution mechanism, in a basic environment, OH- radical, or in acidic conditions, the H2O molecule, initially adsorbs onto the metal active sites (M), creating M-OH. This intermediate then undergoes deprotonation, resulting in the formation of M-O. Subsequently, there are two primary pathways for generating O2. In the first pathway, H2O molecules or OH- ions adsorb onto M-O, leading to product M-OOH, which subsequently experiences a deprotonation to release O2. In the second pathway, two M-O species combine directly to produce O2. Unlike the AEM mechanism, the last step in the LOM involves the direct coupling of O-O free radicals without the formation of M-OOH. Thus, the LOM mechanism has the potential to overcome the constraints imposed by adsorption-energy scaling relationships.

Pure water and seawater electrolysisAEMWE has garnered significant interest as an emerging technology, using a considerably lower concentration of KOH as the electrolyte compared to traditional AWE, while still attaining a substantially higher current density[78-80]. However, challenges persist, such as the formation of K2CO3 due to the reaction between KOH and CO2 from the air, which diminishes electrolyzer performance, along with the issue of waste electrolyte management[81]. Lately, the implementation of pure water as an electrolyte has been proposed to resolve these challenges in an eco-friendly way, without sacrificing stability [Figure 2D][82]. From a cost-efficiency perspective, using pure water, which is about 30 times less expensive than an alkaline solution, has demonstrated greater economic advantages over alkaline-based options[78]. Moreover, selecting DI water enables a more straightforward system design and eases maintenance, resulting in lower operational expenses. In addition, the lack of corrosive electrolytes reduces the requirement for specialized equipment, enhancing water management and electrolyte handling. Despite these advantages, some difficulties remain in pure water-based AEMWE, such as limited ionic conductivity, degradation of the triple phase boundary, impurities in the water, and the need for high overpotential[83-85]. Therefore, addressing these challenges will require innovative material design and optimization of electrode configurations to enhance performance and maintain the long-term stability of pure water-based AEMWE systems.

With freshwater resources becoming increasingly limited, the ocean offers a virtually endless supply, and the hydrogen energy it holds is of significant importance to humanity[86]. Utilizing variable renewable energy for hydrogen production via seawater electrolysis can effectively make use of surplus electricity during times of reduced demand[87-89]. This approach also offers benefits such as straightforward and economical equipment, along with environmentally friendly and efficient production, highlighting its potential for large-scale practical applications [Figure 2E and F][90]. Furthermore, hydrogen produced from seawater electrolysis can serve as a fuel to generate high-purity freshwater, representing an eco-friendly technology that integrates hydrogen production with seawater desalination.

However, in seawater electrolysis, alongside HER and OER, there is competition between the OER and the chlorine evolution reaction (ClER). In mild alkaline seawater electrolytes, the ClER, which produces hypochlorite through a two-electron process, is more thermodynamically forable than the OER via a four-electron process, leading to competition between the two reactions at the anode. Additionally, Cl2 is hazardous and challenging to store and transport, making it crucial to minimize the formation of ClER during seawater electrolysis[91]. More critically, Cl- can degrade the catalyst during the reaction, thus reducing catalytic efficiency. Therefore, researchers are tackling these challenges through various approaches, such as increasing the potential difference between the two reactions or promoting the selective adsorption of oxygen-containing intermediates at active sites by constructing advanced electrocatalysts and optimizing electrode structure[92].

To summarize, KOH-based electrolytes face two major limitations: the formation of K2CO3 due to interaction between KOH and CO2 in the air and high waste electrolyte management costs. To address these challenges, pure water, and seawater electrolytes he been proposed alternatives. Pure water electrolytes are approximately 30 times cheaper than KOH and less corrosive, simplifying equipment design and maintenance. However, their low ionic conductivity and high overpotential remain significant challenges, requiring innovative electrode and material designs. Seawater electrolytes offer a sustainable solution by integrating hydrogen production and desalination using an abundant resource. While economically advantageous and compatible with simple equipment, issues such as ClER and catalyst degradation hinder commercialization. Optimizing catalysts and electrode structures to enhance selective oxygen intermediate adsorption is critical to overcoming these barriers. In conclusion, novel strategies to optimize the benefits and address the limitations of both pure water and seawater electrolytes will be key to the sustainable development and commercialization of AEMWE.

IN SITU CHARACTERIZATIONIn situ characterization entails the real-time observation and examination of materials or systems under conditions that closely replicate actual reaction environments. This characterization enables direct monitoring and analysis of modifications in materials properties, including morphology, structure, and chemical composition, without extracting the materials from their original environment or changing the conditions[93]. Furthermore, combining multiple in situ characterization techniques, each with a distinct focus, is often valued for gaining a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms in complex electrocatalysts.

In situ FTIRFTIR employs infrared (IR) light to induce molecular vibration, allowing for the identification of chemical compounds based on their distinctive IR absorption characteristics [Figure 3A][94]. In the context of electrochemical studies, in situ FTIR can be utilized to detect the presence of species within solutions, and those adsorbed onto electrode surfaces. The IR absorption depends on fluctuations in the dipole moment resulting from molecular vibrations or rotations within the solution. In contrast, on electrode surfaces, the examination of adsorbed species is directed by surface selection rules, focusing on their configuration, bonding, and orientation. The two principal techniques employed in situ FTIR are thin layer mode and attenuated total reflection (ATR) mode. Thin layer mode is straightforward to design and operate, yet it offers lower sensitivity in comparison to ATR mode[95]. On the other hand, the ATR mode, which is more intricate and necessitates meticulous optical adjustment, can mitigate interference from the bulk solution, yielding more discernible spectra with superior signal-to-noise ratios[96].

Figure 3. Schematic configurations for commonly employed in situ techniques in electrochemical reactions. (A) in situ FTIR[94]. Copyright 2022 Springer Nature; (B) in situ Raman spectroscopy[99]. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature; (C) in situ SERS[104]. Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society; (D) in situ XRD[93]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society; (E) in situ XAS[115]. Copyright 2019 Elsevier. FTIR: Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy; SERS: surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy; XRD: X-ray diffraction; XAS: X-ray absorption spectroscopy.

In situ FTIR is an effective tool for gaining insights into the overall chemical properties of a sample, which can assist in the examination of catalyst structure. The selection of appropriate measurement techniques can facilitate the identification of details about the chemical composition, phase variations, and intermediates involved in electrochemical reactions, thereby enhancing the understanding of how catalyst structure relates to its performance[97].

In situ Raman & surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopyRaman spectroscopy is a tool used to examine molecular vibrations, rotations, and other low-frequency modes within a sample[98]. In situ Raman spectroscopy allows for the concurrent observation of molecular transformations and electrochemical reactions, providing a crucial understanding of reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and the intermediates present on electrodes and electrolytes [Figure 3B][99]. Traditional in situ Raman spectroscopy can detect alterations in the bulk phase of catalysts or structural modifications, offering comprehensive insights into the catalyst’s crystalline structure, defects, and chemical bonding[100-102].

In situ Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) is a strategy employed to detect species on catalyst surfaces by incorporating unique and specialized nanostructures, such as Ag, Au, and Cu nanoparticles (NPs)[103]. These nanostructures greatly amplify Raman signals, allowing for the detection of even minute quantities of surface species [Figure 3C][104]. The exceptional sensitivity and spatial resolution of SERS render it a powerful tool for exploring chemical reactions and intermediates on catalyst surfaces.

However, in situ Raman analysis faces challenges related to signal intensity, detection of specific species, and interference from background signals arising from solvents and electrolytes. The naturally weak Raman signals and complex chemical surroundings can impede the identification of target species, particularly at low concentrations or with faint spectral features. Moreover, ensuring device stability during dynamic electrochemical reactions and achieving high temporal resolution to capture rapid molecular changes require advanced instrumentation and data collection techniques[105,106].

In situ XRDXRD is a powerful method for acquiring crystallographic details, including lattice parameters and phase composition[107]. In the field of electrocatalysis, in situ XRD provides significant benefits by allowing real-time observation of structural transformations in catalysts under electrochemical conditions. In contrast to traditional XRD, in situ configurations utilize specialized reaction cells that are compatible with the electrochemical condition, enabling accurate measurements during reactions [Figure 3D][93].

Nevertheless, a drawback of in situ XRD is its lower sensitivity to nanostructured catalysts, especially when particle sizes are below around 5 nm. This issue stems from diffraction limitations linked to small crystallite sizes, which can impede the detailed structural characterization of these materials. Additionally, in situ XRD faces difficulties in resolving local structural characteristics because of its relatively limited spatial resolution[108,109].

In situ XASXAS is based on the concept that atoms absorb X-rays at energy levels that are characteristic of the specific element and its chemical surroundings[110]. The examination of metals typically involves the use of hard X-ray and consists of two key components: X-ray Absorption Near-Edge Structure (XANES) and Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS). XANES is concerned with the electronic and chemical properties of the absorbing atom, highlighting electron transitions from core levels to vacant states close to the absorption edge[111,112]. On the other hand, EXAFS examines the local atomic surroundings of the absorbing atom including neighboring atoms, coordination number, and bond lengths, by analyzing oscillatory patterns caused by the interference of scattered photoelectron wes[113,114].

In situ XAS enhances this functionality by allowing real-time tracking of structural and chemical modifications on catalyst surfaces under actual working electrochemical conditions [Figure 3E][115]. In situ XAS offers a more precise understanding of catalyst behior during operational conditions, capturing dynamic modifications that static analyses might overlook. Furthermore, in situ EXAFS is particularly sensitive to alterations in the local coordination environment of metals, overcoming the limitation of XRD, which has difficulty detecting nanosized materials smaller than 5 nm[93].

However, it might not possess adequate sensitivity to identify slight variations across various chemical environments. Moreover, in situ XAS presents challenges, as the electrochemical cell must be precisely engineered to ensure a consistent condition while permitting X-ray penetration. Besides, the temporal resolution of in situ XAS is relatively limited, making it challenging to accurately observe and investigate reaction systems with fast kinetics or swiftly changing transient intermediates[116,117].

Overall, in situ analysis is a powerful tool for elucidating the chemical properties of reaction intermediates occurring on catalyst and electrode surfaces in the AEMWE reaction environment, along with the structural and chemical changes of the catalyst and electrode itself. Techniques such as in situ FTIR and Raman are effective tools for analyzing reaction intermediates, while in situ XRD and XAS are useful for monitoring structural changes. These insights enable a more precise understanding of electrocatalytic mechanisms in AEMWE. However, the high cost of specialized equipment, complex operation requirements, and challenging data processes limit its feasibility for large-scale applications. Therefore, addressing these challenges will require significant efforts in developing cost-effective techniques, simplifying operational setups, and advancing data processing methods.

ELECTROCATALYSTS FOR AEMWEConstructing HER and OER electrocatalysts that feature low overpotential, robust durability, and cost-effectiveness is crucial while presenting difficulties in lowering the costs associated with hydrogen production. To address these obstacles, HER and OER electrocatalysts should be strategically engineered to enhance both activity and stability concurrently. Herein, we highlight the latest progress in advanced electrocatalytic materials for AEMWE across alkaline, pure water, and seawater systems.

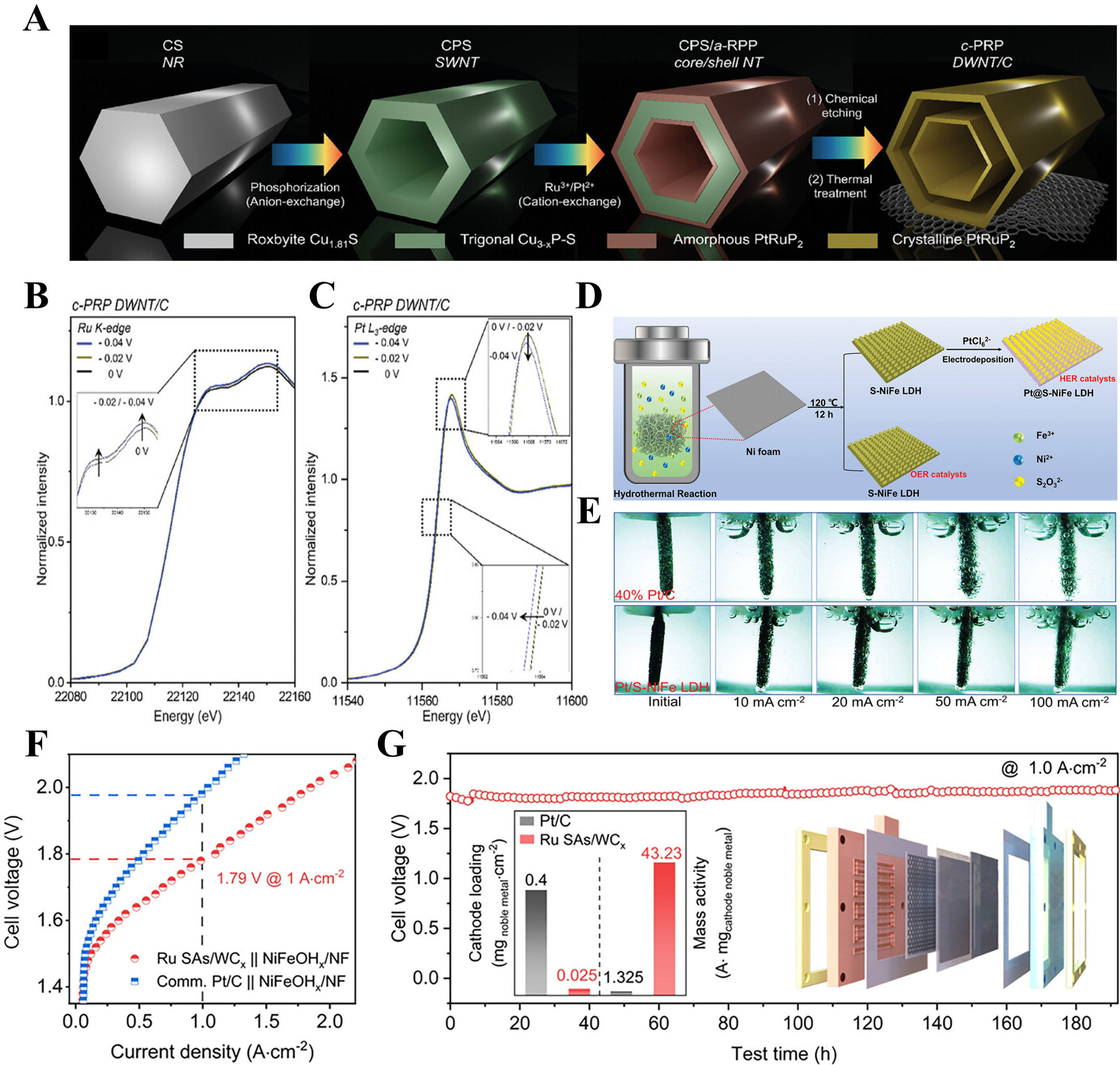

HER electrocatalyst for cathodePrecious metalsPrecious metals, including Pt, Pd, Ru, Ir, and Rh, exhibit excellent electrocatalytic performance for HER. Nonetheless, the commercial usage of these precious metal-based electrocatalysts is limited by their rarity and high expense. To address this issue, the strategic development of electrocatalysts with reduced metal content and optimized metal utilization is crucial. For example, Hong et al.[118] synthesized Heusler-type PtRuP2 double-walled nanotube (c-PRP DWNT/C) HER catalysts using consecutive anion and dual cation exchange processes, chemical etching, and pyrolysis following attachment to carbon black [Figure 4A]. The resulting c-PRP DWNT/C-based AEM water electrolyzer demonstrated an impressive current density of 9.4 A cm-2 at 2.0 V and stable operation at 1.0 A cm-2 at 60 °C for approximately 270 h, surpassing the performance of state-of-the-art AEM and proton exchange membrane (PEM) water electrolyzers. This high performance is attributed to the synergistic interaction between Pt and Ru dual sites, which provide numerous active sites to enhance HER kinetics. This facilitates sequential processes, including water activation and dissociation at Ru sites, followed by H2 generation at Pt sites. The cooperative interaction between the Ru and Pt active sites, which enhances HER activity in alkaline media, was further clarified through in situ XAS. As revealed in Figure 4B, the Ru K-edge XANES spectra at -0.02 V for c-PRP DWNT/C showed an increase in white line intensity, indicating the formation of Ru intermediates through OH- and H2O chemisorption. Additionally, in situ Ru K-edge Fourier-transformation EXAFS (FT-EXAFS) suggested that Ru sites in PtRuP2 promote water dissociation, while the Pt in PtRuP2 enhances HER kinetics by serving as a cooperative site for H+ adsorption and H2 production, as evidenced by a decrease in white line intensity in the operando Pt L3-edge, indicating the formation of H intermediates [Figure 4C]. Lei et al.[119] developed a self-supporting HER catalyst by fabricating Pt quantum dots on sulfur-doped NiFe layered double hydroxide (Pt@S-NiFe LDH) via facile hydrothermal synthesis and electrodeposition process [Figure 4D]. This method stands out for its mild conditions, low consumption of precious metals, and utilization of economically viable materials, positioning it as a compelling option for industrial applications. During electrolysis, large volumes of hydrogen and oxygen gases evolve, leading to bubble formation at the electrocatalyst-electrolyte interface, which can hinder the interaction between active sites and reactants. This issue is particularly prevalent at high current densities, which are typical of industrial operations, and therefore bubble release behior is a critical factor. It is noteworthy that Pt@S-NiFe LDH exhibits an exceptional ability to prevent the accumulation of bubbles on its surface, even when subjected to elevated current densities. The nanoengineering of Pt quantum dots on NiFe LDH has been demonstrated to effectively minimize the negative impact of gas bubble adhesion. This design facilitates efficient mass transfer and rapid bubble release, allowing the active sites to remain exposed to reactants and thereby enhancing reaction kinetics [Figure 4E]. Consequently, at an industrially relevant temperature of 65 °C, the Pt@S-NiFe LDH-based electrolyzer achieves a current density of 100 mA cm-2 at just 1.62 V, outperforming commercial catalysts (40% Pt/C//IrO2).

Figure 4. Precious metal-based electrocatalysts for HER in AEMWE. (A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis process of c-PRP DWNT/C; (B) in situ Ru K-edge XANES spectra and (C) in situ Pt L-edge XANES spectra for c-PRP DWNT/C[118]. Copyright 2024 John Wiley & Sons; (D) Schematic representation of the fabrication steps for Pt@S-NiFe LDH; (E) Digital images showcasing hydrogen release behior[119]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons; (F) Polarization curves of AEM water electrolyzer using Ru SAs/WCx; (G) Durability cell voltage-time plots for the AEMWE based on Ru SAs/WCx[121]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure; AEM: anion exchange membrane; c-PRP DWNT/C: Heusler-type PtRuP2 double-walled nanotube; Pt@S-NiFe LDH: Pt quantum dots on sulfur-doped NiFe layered double hydroxide; Ru SAs/WCx: Ru SA catalyst anchored on tungsten carbide; SA: single-atom.

Ru has garnered significant interest as a more affordable alternative to Pt, exhibiting comparable energy barriers for water splitting and hydrogen binding strengths. For instance, Wang et al.[120] designed an innovative Ru-based hybrid HER catalyst, featuring atomically layered Ru nanoclusters with adjacent Ru single atomic sites anchored onto a Ni hydr(oxy)oxide substrate (NS-Ru@NiHO/Ni5P4), synthesized via electrochemical deposition method. Theoretical studies demonstrated that the H2O molecules preferentially dissociate at the single-atom (SA) Ru sites, followed by *H adsorption facilitated by bridging Ru-H activation in Ru nanoclusters, which enhances the kinetics of the Volmer-Heyrovsky HER mechanism. As a result, the assembled AEM water electrolyzer exhibited a current density of 1.0 A cm-2 at a low cell voltage of 1.7 V. Lin et al.[121] presented a Ru SA catalyst anchored on tungsten carbide (Ru SAs/WCx) for HER, fabricated via dopamine-assisted molecular assembly followed by pyrolysis. They proposed that the SA Ru sites exhibit a puncture effect that effectively mitigates OH- blockages, significantly enhancing the HER performance in alkaline conditions. Moreover, density functional theory (DFT) calculations indicated that the isolated Ru atoms reduce the local OH- binding energy, thereby alleviating OH- blockages and forming dual-functional interfaces involving Ru atoms and the support, which facilitates H2O dissociation. As a result, the AEM water electrolyzer incorporating Ru SAs/WCx revealed a current density of 1.0 A cm-2 at a cell voltage of just 1.79 V, as evidenced by Figure 4F. Furthermore, the electrolyzer exhibited remarkable stability, operating for 190 h at 1.0 A cm-2 with minimal performance degradation [Figure 4G]. Yao et al.[122] introduced a Ni SA-modified Ru NP catalyst with a defective carbon bridging structure (UP-RuNiSAs/C) synthesized via a unique unipolar pulse electrodeposition (UPED) technique. Unlike traditional continuous potentiostatic deposition, the UPED method minimizes concentration polarization, enabling precise control over the deposition of Ni SA onto defect-rich carbon through periodic pulses. Theoretical calculations indicated that incorporating NiSAs into the Ru nanocrystalline framework substantially lowers the adsorption energy of OHad on Ru. Additionally, the carbon bridge effect of defective carbon facilitates OH- charge redistribution between Ni and Ru, further reducing OHad adsorption on Ru. The optimized AEM electrolyzer using the UP-RuNiSAs/C catalyst achieved a cell voltage of just 1.95 V at a current density of 1 A cm-2 at 70 °C, maintaining stable operation for 250 h at 1 A cm-2.

Os, the densest and most affordable metal in the Pt group, possesses a similar electronic structure to Pt but is seldom utilized in water electrolysis due to its poor proton adsorption ability. However, its limited catalytic performance can be improved by further adjustments to its electronic structure. For example, Li et al.[123] reported a phosphorus-doped Os (P-Os) catalyst for alkaline HER using a rapid 20 s microwe plasma technique. Both theoretical calculations and experimental data confirmed that the modulation of the electronic structure at the Os sites, facilitated by p-d orbital hybridization between P and Os, enhances H2O dissociation and optimizes hydrogen intermediate adsorption/desorption, thereby improving catalytic performance. Therefore, an AEM electrolyzer with the optimized P-Os cathode attained current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm-2 at 1.86 and 2.02 V, respectively, and operated continuously at 500 mA cm-2 for over 100 h, indicating its potential for industrial applications.

Non-precious metalsTransition metals possessing a d-electronic configuration, particularly Ni, Co, and Fe, are commonly investigated as HER electrocatalysts due to their promising catalytic characteristics. In particular, alloying or doping Ni with additional elements seeks to modify its electronic structure, thereby enhancing its catalytic performance for HER. For instance, Li et al.[124] developed a freestanding binder-free hierarchical electrode using a simple in situ approach, where Ni NPs were encapsulated within N-doped carbonized wood (Ni@NCW) [Figure 5A]. The carbonized wood, with an ordered hierarchical 3D porous structure, serves as an ideal carbon matrix for catalyst nucleation and active component loading, promoting efficient mass diffusion. The incorporation of N-doped carbon nanotubes in the carbonized wood further facilitates electron transfer within the electrode and enhances the durability of the active metal components. Owing to these advantageous properties, an AEM water electrolyzer utilizing the freestanding Ni@NCW electrode operated at a lower cell voltage of 2.43 V to reach an industrial-scale current of 4.0 A, maintaining remarkable stability at 4.0 A for 18 h [Figure 5B and C]. Lee et al.[125] designed Ni-Mo catalysts (Ni3Mo) as the cathode for an AEM water electrolyzer through a co-precipitation method to form hydroxides, followed by pyrolysis under H2 flow. Notably, after applying a mild activation process by maintaining a current density of 50 mA cm-2 for 6 h, the cell demonstrated its best performance, achieving 1.82 V at 1 A cm-2, surpassing the performance of the 40 wt% Pt/C catalyst. It was observed that a considerable amount of Mo dissolved from the cathode and migrated to other parts of the cell. As depicted in Figure 5D, DFT calculations revealed that Mo dissolution occurs from the surface of Ni3Mo, but the redeposition of MoO3 onto the surface is thermodynamically fored. The dissolution of Mo enhances water dissociation on the Ni3Mo surface, while the adsorbed MoO3 species reduce hydrogen adsorption, thereby improving the HER activity. Chen et al.[126] synthesized a hierarchical composite electrocatalyst consisting of heterogeneous Ni4Mo/NiMoO4 NPs (NiMoOx NPs) anchored on mesoporous carbon CMK-3 (NiMoOx@CMK-3) for HER. The robust interaction between the NiMoOx NPs and the CMK-3 support matrix efficiently stabilizes the catalytic active Ni4Mo/NiMoO4 heterostructure by modifying the local geometric and electronic environments, resulting in optimizing the exposure of active sites and enhancing electron transfer capabilities. Furthermore, the heterogeneous interface between Ni4Mo and NiMoO4 facilitates the stabilization of the forable MoO42- species. As observed in Figure 5E, due to the robust metal-metal oxide-support interaction, the AEM water electrolyzer employing NiMoOx@CMK-3 exhibited a low cell voltage of 1.965 V at 1 A cm-2 and maintained excellent stability, with minimal decay over 400 h at 1 A cm-2. Moreover, in situ Raman spectroscopy demonstrated that a partial combination of MoO42- from NiMoO4 with newly generated MoO42- from dissolved Mo in NiMoOx@CMK-3, facilitated the rapid formation of polymerized Mo2O72- species [Figure 5F]. This process significantly improved the HER under an alkaline environment by promoting the formation of active Mo-H* intermediates. Zhao et al.[127] introduced a boron and vanadium co-doped nickel phosphide electrode (B, V-Ni2P) that effectively modifies the intrinsic electronic structure of Ni2P, thereby enhancing HER activity. Both experimental and theoretical findings demonstrated that the inclusion of V significantly accelerated the H2O dissociation, while the combined effect of B and V promoted the desorption of *H intermediates. Thus, an AEM water electrolyzer using B, V-Ni2P maintained stable performance, achieving current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm-2 at cell voltages of 1.78 and 1.92 V, respectively. Interestingly, under a constant cell voltage of 1.8 V, the electrolyzer achieved current densities of 460, 475, 512, and 535 mA cm-2 in seawater electrolysis across devices I-IV, while demonstrating stable performance over 30 h of continuous operation [Figure 5G].

Figure 5. Transition metal-based electrocatalysts for HER in AEMWE. (A) Schematic showing the fabrication process of Ni@NCW; (B) Chronopotentiometric curves for Ni@NCW under multiple potentials; (C) Chronopotentiometric curve at 4.0 A and the digital image of AEM water electrolyzer utilizing Ni@NCW[124]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons; (D) Schematic depicting the HER process on MoO3/Ni3Mo in an alkaline environment[125]. Copyright 2023 American Chemical Society; (E) Polarization curves of AEM water electrolyzer using NiMoOx@CMK-3 as a cathode; (F) In situ Raman spectra for NiMoOx@CMK-3 in 1 M KOH[126]. Copyright 2023 Elsevier; (G) Schemes of various operational modes for AEM seawater electrolyzers[127]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons; (H) Chronopotentiometric curve of the AEM water electrolyzer employing WS2 superstructure as a cathodic catalyst[129]. Copyright 2024 Springer Nature. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; HER: hydrogen evolution reaction; NCW: N-doped carbonized wood; AEM: anion exchange membrane.

Apart from Ni-based electrocatalysts, other transition metal-based catalysts show great potential as cost-effective options. Moreover, these materials are well-suited for use in the cathode of AEM water electrolyzers due to their efficient HER kinetics. For example, Zhang et al.[128] employed a universal ligand-exchange [metal-organic framework (MOF)-on-MOF] modulation strategy to fabricate ultrafine Fe2P and Co2P NPs, which were stably anchored on N and P co-doped carbon porous nanosheets (Fe2P-Co2P/NPC). Theoretical calculations suggested that the electron density in Fe2P-Co2P/NPC was redistributed, with enrichment at the P site, due to the reversal of electron flow from Fe and Co to the P site. This process resulted in the reallocation of active sites, effectively reducing the energy barrier for HER. Consequently, a practical AEM water electrolyzer incorporating Fe2P-Co2P/NPC indicated a low cell voltage of 1.73 V at 1.0 A cm-2 in 1.0 M KOH. Furthermore, the electrolyzer exhibited stable performance without any degradation at 1.0 A cm-2 over 1000 h of continuous operation, maintaining an energy efficiency of over 85%. Xie et al.[129] constructed a flexible tungsten disulfide (WS2) superstructure as a cathodic catalyst, characterized by bond-free van der Waals interaction between nanosheets with a low Young’s modulus, providing exceptional mechanical flexibility. The catalyst also featured stepped-edge defects on the nanosheets, which boosted activity and created an advantageous reaction microenvironment. This unique WS2 superstructure efficiently withstood the stress of high-density gas-liquid exchanges, promoting mass transfer and ensuring outstanding long-term durability under industrial-scale current density. As a result, an AEM water electrolyzer equipped with this cathodic catalyst achieved a cell voltage of 1.70 V, preserving a current density of 1 A cm-2 over 1000 h [Figure 5H].

OER electrocatalyst for anodePrecious metalsPrecious metals and metal oxides he been regarded as highly effective electrode materials for OER, with RuO2 and IrO2 often seen as the benchmark electrocatalysts for OER. However, because of the high costs and dissolution issues associated with these materials, various modification strategies he been suggested to enhance electrocatalyst activity and stability while reducing expenses. For example, Du et al.[58] designed hollow Co-based N-doped porous carbon spheres decorated with ultrafine Ru nanoclusters (HS-RuCo/NC) as effective OER catalysts by pyrolyzing bimetallic zeolite imidazolate frameworks loaded with Ru (III) ions [Figure 6A]. Both theoretical and experimental investigation indicated that the synergistic interaction between the in situ-formed RuO2 coupled with Co3O4 helped optimize the electronic structure of the RuO2/Co3O4 heterostructure, reducing the energy barrier for OER. Additionally, Co3O4 played a crucial role in preventing the over-oxidation of RuO2, thereby significantly improving the catalyst’s stability. As a result, an AEM water electrolyzer incorporating HS-RuCo/NC exhibited a cell voltage of 2.07 V to reach a current density of 1 A cm-2, maintaining stable performance without significant potential degradation over 100 h at 500 mA cm-2. Kang et al.[130] presented a corrosion-resistant RuMoNi electrocatalyst, where in situ-formed MoO42- ions-generated by the leaching of Mo during electrochemical reconstruction-serve to repel chloride ions derived from seawater [Figure 6B]. The synthesis of the RuMoNi electrocatalyst was achieved through a two-step process involving a hydrothermal method followed by electrochemical activation. After the hydrothermal treatment, the product consisted of nearly parallel nanorods uniformly coated with NPs. Following electrochemical oxidation, the RuMoNi electrocatalyst retained its nanorod structure, with a porous surface formed in the process. Consequently, the AEM seawater electrolyzer using this RuMoNi electrocatalyst demonstrated enhanced performance, with a high activity (1.72 V at 1 A cm-2), improved cell efficiency (77.9% at 500 mA cm-2), and long-term stability (maintaining 500 mA cm-2 for 240 h) due to its robust corrosion-resistant layer [Figure 6C-E].

Figure 6. Precious metal-based electrocatalysts for OER in AEMWE. (A) Scheme of the fabrication procedure for Ru-O/N-C-NH3[58]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons; (B) Schematic illustrating the structure and corrosion-resistant approach of RuMoNi electrocatalyst; (C) Polarization curves of the AEM water electrolyzer with RuMoNi in 1.0 M KOH + seawater at 20 °C and 6.0 M KOH + seawater at 60 °C; (D) Long-term stability test of the AEM water electrolyzer using RuMoNi at 500 mA cm-2 in a 1.0 M KOH + seawater electrolyte; (E) Performance comparison of the RuMoNi-catalyzed electrolyzer with other reported AEM seawater electrolyzers[130]. Copyright 2023 Springer Nature; Durability tests for Co3-xPdxO4 catalysts on MnO2-coated Ni foam substrates at (F) 200 mA cm-2 and (G) 1 A cm-2 in natural seawater electrolyte[131]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; AEM: anion exchange membrane.

In addition to Ru, theoretical calculations indicate that Pd exhibits excellent capabilities for H2O adsorption and dissociation, which can contribute to improved OER catalytic performance. For instance, Wang et al.[131] introduced a proton-adsorption-enhancing approach for synthesizing palladium-doped cobalt oxide (Co3-xPdxO4) catalysts designed for OER in neutral seawater splitting. Both experimental results and theoretical studies highlighted the synergetic interaction between Co active sites and strong proton adsorption (SPA) cations. The Co active sites adsorbed OER intermediates, while SPA cations, such as Pd, facilitated the dissociation of H2O molecules, thereby boosting OER activity in neutral conditions. As a result, an AEM seawater electrolyzer utilizing Co3-xPdxO4 OER catalysts maintained stable seawater splitting performance for 450 h at 0.2 A cm-2 and for 20 h at 1 A cm-2 [Figure 6F and G].

Non-precious metalsNi-based oxides, among transition metal-based OER catalysts, he shown superior OER performance due to their high-water oxidation potential, surpassing other catalysts. For example, Park et al.[132] constructed a three-dimensional unified electrode by electrodepositing nickel-iron oxyhydroxide (NiFeOOH) directly onto a GDL to serve as the anode in an AEM water electrolyzer [Figure 7A]. Unlike traditional electrodes, which are typically composed of separate catalysts and GDL, this single-component integrated electrode enhanced the electrical connectivity between the catalyst and GDL, resulting in improved performance and stability. As shown in Figure 7B, the unified AEM water electrolyzer revealed exceptional current density, achieving 3.6 A cm-2 at 1.9 V. Even with a non-noble metal catalyst, the performance of this unified AEMWE was twice as high as that of a conventional AEM water electrolyzer with a noble metal catalyst. Moreover, even with AEM degradation, the unified AEM water electrolyzer demonstrated stable performance, maintaining a current density of 500 mA cm-2 for 100 h and 3000 mA cm-2 for 24 h. Thangel et al.[133] designed highly efficient OER catalysts by anchoring Ni3N particles onto an electrochemically reconstructed amorphous oxy-hydroxides surface, leading to V-NiFe(OOH)/Ni3N structures. This distinctive amorphous-crystalline interface, abundant in active sites, significantly improved electron transport and accelerated OER kinetics at the electrode-electrolyte interface. As seen in Figure 7C, to pinpoint the actual active sites and intermediates of the V-NiFe(OOH)/Ni3N catalysts, in situ Raman spectroscopy measurements were carried out. The in situ Raman analysis revealed a substantial increase in peak intensity after 1.35 V, which was associated with the formation of FeOOH from Fe2O3 reconstruction, acting as the true catalytic phase during OER. Additionally, the elevating intensity of NiOOH peaks at higher overpotentials revealed the continuous formation of NiOOH during OER, suggesting that the catalyst was both chemically stable and electrically conductive. This structural synergy contributed to the enhanced activity of the V-NiFeOOH/Ni3N catalyst. As a result, the AEM water electrolyzer using the V-NiFeOOH/Ni3N/NF electrode demonstrated an impressive current density of 685 mA cmgeo-2 at 1.85 Vcell and 70 °C, maintaining stability for over 500 h in ultra-pure water-electrolyte [Figure 7D and E]. Yang et al.[134] synthesized a multiple-layered ternary NiFeM (M = Co, Mn, or Cu) nanofoam as a catalyst for OER, constructed from self-assembled ultrathin nanowires [Figure 7F]. Each nanowire featured a multilayered core-shell structure with amorphous oxide shells and metallic alloy cores, which enhanced both surface OER activity and electrical conductivity through the core. Among the catalysts tested, NiFeCo demonstrated the highest catalytic activity and stability in a half-cell with concentrated alkaline electrolytes. In contrast, the NiFeMn catalyst exhibited a significantly improved current density of 2.0 A cm-2 at 1.7 V in an AEM water electrolyzer with 0.1 M KOH, surpassing the IrO2 [Figure 7G]. Additionally, the NiFeCu catalyst recorded a promising current density of 1.2 A cm-2 at approximately 2.3 V when pure water was supplied, showing performance close to that of IrO2, particularly at high current densities [Figure 7H].

Figure 7. Ni-based electrocatalysts for OER in AEMWE. (A) Schematic illustration of the conventional electrode and unified electrode; (B) Polarization curves of AEM water electrolyzer based on the unified electrode[132]. Copyright 2022 American Chemical Society; (C) in situ Raman spectra of V-NiFeOOH/Ni3N catalysts in 1 M KOH; (D) Schematic illustration of AEM ultrapure water electrolyzer setup; (E) Polarization curves of AEM water electrolyzer using V-NiFeOOH/Ni3N catalysts in ultrapure water-electrolyte[133], Copyright 2022 John Wiley & Sons; (F) Scheme of creating nanofoam-like NiFeM catalysts; Multiple polarization curves of NiFeM catalysts in (G) 0.1 M KOH and (H) pure DI water[134]. Copyright 2024 John Wiley & Sons. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; AEM: anion exchange membrane.

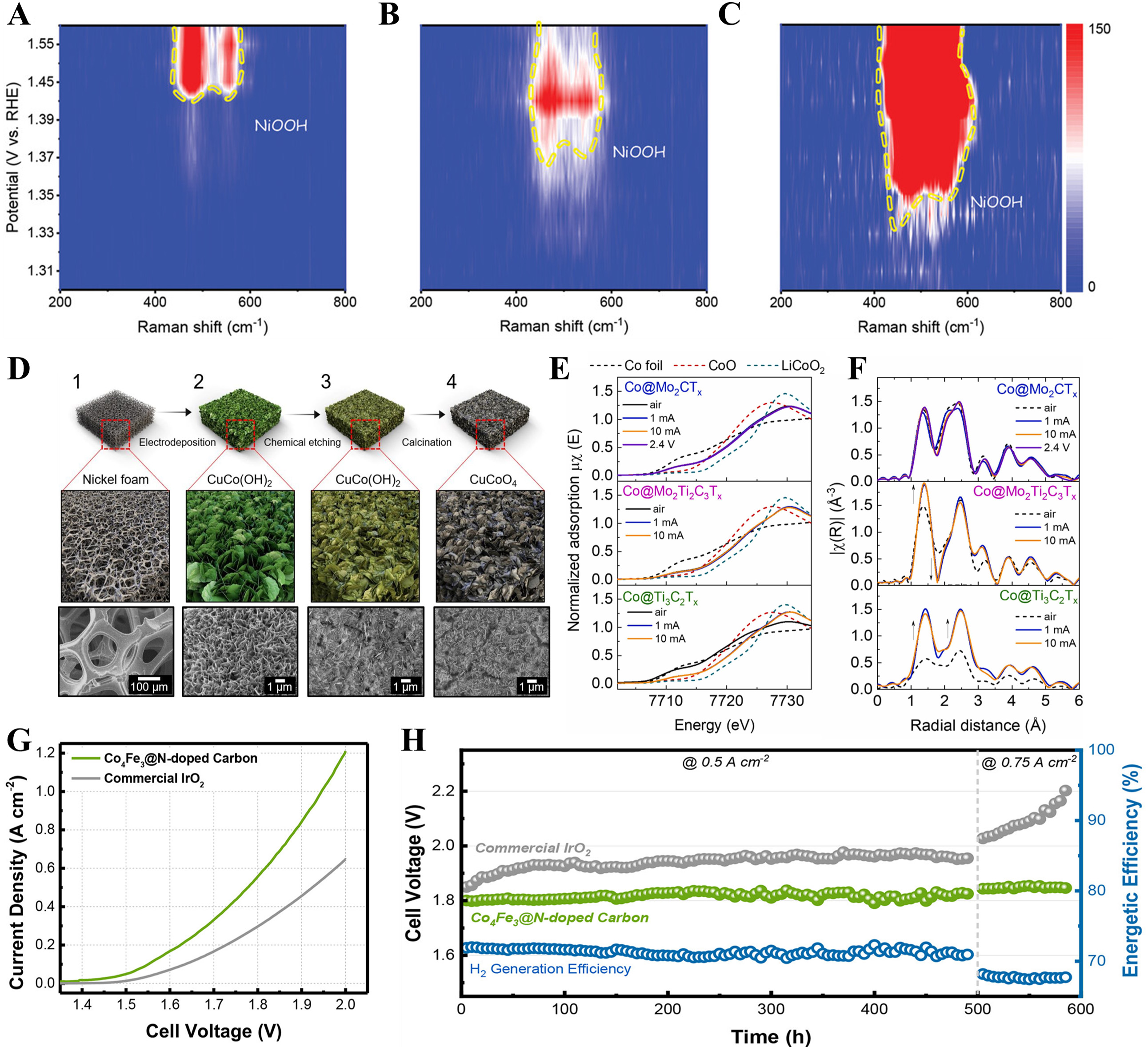

Aside from Ni, other transition metals, including Co, Fe, Cu, and Cu, could also enhance OER performance. For instance, Zhao et al.[135] utilized a high-entropy Co and Mo co-doped NiFe hydroxide (Co, Mo-NiFe LDH) as a precursor, leveraging the in situ leaching of Mo atoms during OER operation to create Co-doped NiFe oxyhydroxide (Co, VM-NiFe OOH) with coexisting cation vacancies. The reconfiguration process from Co, Mo-NiFe LDH to Co, VM-NiFe OOH was monitored using in situ electrochemical spectroscopy. In situ Raman spectroscopy showed that Co doping reduced the energetic barrier for oxidation, while the vacancies formed by Mo leaching generated more high-valence active species, enhancing OER performance [Figure 8A-C]. Thus, the AEM water electrolyzer incorporating the Co, Mo-NiFe LDH catalyst achieved a notably low voltage of 1.94 V at a current density of 2 A (electrode area about 4 cm2) in 1 M KOH, maintaining stable performance for 130 h with a cell voltage fluctuation of less than 20 mV. Park et al.[64] constructed hierarchically structured CuCo-oxide (CCO) catalysts via electrochemical co-depositing of Cu and Co hydroxides onto Ni foam, followed by surface chemical etching and calcination [Figure 8D]. The chemical etching process introduced oxygen vacancies in the CCO, enhancing its electrical conductivity and promoting OER. Consequently, an AEM water electrolyzer, using CCO as the anode, delivered outstanding OER performance, achieving 1.39 A cm-2 at 1.8 Vcell. Additionally, the AEM water electrolyzer exhibited strong durability, with the initial overpotential of 1.66 Vcell gradually increasing to 1.74 Vcell after 64 h at a high current density of 500 mA cm-2, retaining 82% of its original performance. Park et al.[136] reported a CuCo2O4 (CCO*) electrocatalyst with a chestnut-burr-like morphology, directly grown on Ni foam substrates and featuring hierarchical mass transfer pathways. This distinctive structure, which eliminated the need for binders and conductive agents, enabled a high catalyst loading without electrode degradation, leading to enhanced OER performance. Leveraging these advantages, a resulting AEM water electrolyzer equipped with CCO* for the anode catalyst showed an impressive current density of 1.4 A cm-2 at 1.85 Vcell and 70 °C, while continuously delivering 500 mA cm-2 for over 12 h in 1 M KOH at 45 °C. Park et al.[137] designed a CeO2/CoFeCe-LDH heterostructure as an efficient OER catalyst. The ternary CoFeCe-LDH (CoFeCe0.1), with Ce, doped into the CoFe-LDH lattice, exhibited enhanced OER performance due to modifications in its electronic structure. Further doping with Ce led to the formation of a self-assembled CeO2/CoFeCe-LDH (CoFeCe0.5) heterostructure, which formed an active interface between CeO2 and CoFeCe-LDH. Therefore, the AEM electrolyzer incorporating the CoFeCe0.5 catalyst indicated both reduced ohmic and activation losses, achieving an impressive current density of 2.7 A cm-2 at 1.8 Vcell, surpassing the performance of AEM electrolyzers using IrO2 as the OER catalyst. Park et al.[138] explored Co@MXene catalysts by seeding commercial Co NPs onto three different MXene supports (Ti3C2Tx, Mo2Ti3C2Tx, and Mo2CTx). The strong Mo-Co interaction between Mo2CTx and Co NPs was identified as the key factor enhancing the intrinsic OER activity of Co, with Co@Mo2CTx achieving an exceptional performance of 2.11 A cm-2 at 1.8 V, maintaining stability for over 700 h. Furthermore, in situ XAS analyses revealed minimal changes in the oxidation state and crystal structure of Co@Mo2CTx and Co@Mo2Ti3C2Tx, indicating the stability of the active site under alkaline OER conditions [Figure 8E and F]. In contrast, Co@Ti3C2Tx underwent continuous oxidation. This analysis further confirmed that the Mo-O layer protected Co@Mo2CTx and Co@Mo2Ti3C2Tx, emphasizing the significance of Mo-Co interaction over traditional notions of electrical conductivity in MXene-based electrocatalysts. Park et al.[139] developed a hierarchically structured OER electrocatalyst consisting of a Co4Fe3 core and N-doped graphitic carbon shell, synthesized by pyrolyzing Co/Fe-Prussian blue analogue templates. The Co4Fe3@N-doped graphitic carbon catalyst showed remarkable OER performance and stability, due to the combined effects of abundant Co3+ species, a large electrochemically active surface area, a highly conductive bimetallic core, and oxygen-rich functional groups with pyridinic N in the N-doped carbon shell. Thus, an AEM water electrolyzer utilizing this catalyst revealed lower overpotential, 139 % higher energy efficiency, and a 70-fold lower degradation rate than a commercial IrO2-based system [Figure 8G and H].

Figure 8. Other transition metal-based electrocatalysts for OER in AEMWE. (A-C) Time-resolved in situ Raman spectra of catalysts in 1.0 M KOH[135]. Copyright 2023 John Wiley & Sons; (D) Schematic diagram showing the fabrication process of the chemically etched CuCoO4 catalyst[63]. Copyright 2020 Elsevier; In situ Co K-edge XAS spectra of Co@MXene at 1 mA cm-2 and 10 mA cm-2 in (E) XANES and (F) FT-EXAFS[138]. Copyright 2024 Elsevier; (G) Polarization curves, (H) Chronopotentiometric curves, and energetic efficiency of AEM water electrolyzer based on Co4Fe3@N-doped graphitic carbon catalyst[139]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; XAS: X-ray absorption spectroscopy; XANES: X-ray absorption near-edge structure; FT-EXAFS: Fourier-transformation extended X-ray absorption fine structure; AEM: anion exchange membrane.

Bifunctional electrocatalyst for both cathode and anodeBifunctional electrocatalysts are crucial for efficient water electrolysis, as they catalyze both HER and OER simultaneously, reducing energy losses and improving overall efficiency for sustainable hydrogen production. Additionally, bifunctional electrocatalysts are essential for creating a cost-effective, compact, and efficient water electrolyzer, streamlining design by eliminating the need for separate catalysts and ensuring balanced performance[140]. Thus, numerous bifunctional catalyst materials were carefully developed and constructed to fulfill the specific and challenging requirements of AEMWE.

For example, Tran et al.[141] proposed a tunable engineering strategy to modify the structure of Ni layered double hydroxide (LDH) through an in situ doping method involving dual transition metals, Mn and Fe, followed by partial substitution or surface adsorption with atomic Pt, resulting in the development of the PtSA-Mn,Fe-Ni LDH bifunctional electrocatalyst [Figure 9A]. The incorporation of Pt SAs, combined with the co-doping of transition metal moieties into the Ni LDH framework, resulted in a synergistic interaction that enhanced electrochemical performance by increasing the number of electroactive sites and improving structural stability. To gain deeper insights into the origin and factors contributing to its remarkable HER and OER activity and stability, in situ Raman spectroscopy was employed. As revealed in Figure 9B, the in situ Raman spectra of PtSA-Mn,Fe-Ni LDHs during HER at varying potentials showed a reduction in NiO mode peak intensities as the potential shifted from OCP to the HER range, indicating the reduction of Ni(OH)2 to Ni. Even at a potential more negative than -0.2 V, unreduced Ni(OH)2 was still detected, suggesting its structural stability under H2-evolving conditions. As illustrated in Figure 9C, the in situ Raman spectra of PtSA-Mn,Fe-Ni LDHs during OER showed no significant structural changes up to 1.25 V, but at 1.3 V and above, the intensity of NiOOH-related vibration modes increased, indicating the conversion of Ni(OH)2 to NiOOH as the catalytically active phase, with the appearance of a new Ni-O stretching peak and a broad feature assigned to superoxide species. Utilizing the optimized structure, the AEM water electrolyzer stack with PtSA-Mn,Fe-Ni LDHs as both the anode and cathode achieved a cell voltage of 1.79 V at 500 mA cm-2, demonstrating outstanding durability over a 600 h operation period [Figure 9D]. Shen et al.[142] developed a method involving room-temperature reduction followed by low-temperature calcination at 300 °C to synthesize Ru NPs, referred to as Ru-BOx-OH-300, characterized by surface-enriched hydroxyl and borate species. Both experimental and theoretical analyses revealed that these surface species modulate the Ru catalytic sites in Ru-BOx-OH-300, facilitating H2O dissociation and lowering the activation energy for water splitting to generate O2 and H2. As a result, an AEM seawater electrolyzer using Ru-BOx-OH-300 as both the anodic and cathodic electrocatalysts at 25 °C achieved current densities of 500 and 1000 mA cm-2 at 1.73 V and 1.95 V, respectively, while maintaining excellent stability over 400 h without significant performance degradation. Chang et al.[143] presented a synthesis of iron phosphosulfate (Fe2P2S6) nanocrystal (NC) catalysts grown in situ on carbon paper using a combination of chemical vapor deposition and solvothermal treatment. Detailed analyses, including X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and Raman, revealed that Fe2P2S6 NCs were primarily responsible for HER, while the surface FeOOH on the Fe2P2S6 NCs acted as the true active phase for OER. In a practical AEM water electrolyzer, the bifunctional Fe2P2S6 NCs achieved an impressive current density of 370 mA cm-2 at 1.8 V. Furthermore, the Fe2P2S6 NCs exhibited significantly greater stability than Pt-IrO2, maintaining performance at 300 mA cm-2 for 24 h without noticeable degradation. Liang et al.[144] proposed a liquid-phase self-assembly approach to fabricate the coral-like Co3V2O8 nanoarrays on a nickel foam (CoVO@NF) [Figure 9E]. The unique structure not only provided abundant active sites to boost catalytic activity but also created ample space to accommodate volume fluctuations and mitigate stress, thereby promoting stability. The HER and OER activities were further improved by adjusting the electronic structure through nitridation and phosphorization, respectively, which strengthened the metal-H bond for optimized hydrogen adsorption and promoted proton transfer, thereby enhancing the conversion of oxygen-containing intermediates. Consequently, an AEM water electrolyzer employing CoN/VN@NF as the cathode and P-CoVO@NF as the anode delivered only 1.76 V to reach a current density of 500 mA cm-2 in 1.0 M KOH at 70 °C, with performance degradation of just 1.01% after 1000 h [Figure 9F]. Quan et al.[145] introduced a liquid-assisted chemical vapor deposition approach to concurrently anchor SA Ru sites on the sidewalls and Janus Ni/NiO NPs at the apex of nanocities, effectively activating N-doped carbon nanotube arrays (Ni/NiO@Ru-NC). Both theoretical and experimental investigations suggested that the confinement of Ru single atoms, along with Janus Ni/NiO NPs, modulated electron distribution through potent orbital interactions, activating the NC nanotubes from sidewall to apex, thereby improving water-splitting performance. As displayed in Figure 9G, the Ni/NiO@Ru-NC||Ni/NiO@Ru-NC system delivered 100 mA cm-2 at an applied voltage of only 1.595 V, significantly outperforming RuO2||Pt/C and Ni/NiO@NC||Ni/NiO@NC in a traditional two-electrode setup. Additionally, when incorporated into an AEM water electrolyzer, the ionomer-free, self-supported Ni/NiO@Ru-NC electrode functioned as a highly efficient and durable bifunctional electrocatalyst, maintaining stability for 50 h at 500 mA cm-2 [Figure 9H]. Table 1 summarizes the performance metrics of various electrocatalysts for AEMWE.

Figure 9. Bifunctional electrocatalysts for HER/OER in AEMWE. (A) Scheme of the fabrication processes for PtSA-Mn, Fe-Ni LDHs on NF; In situ Raman spectra of PtSA-Mn, Fe-Ni LDHs for (B) HER and (C) OER processes in an alkaline environment; (D) Long-term stability test of AEM water electrolyzer employing PtSA-Mn, Fe-Ni LDH catalysts for both anode and cathode[141]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society; (E) Synthesis illustration of CoN/VN@NF and P-CoVO@NF; (F) Durability test at 1.76 V under 70 °C[144]. Copyright 2024 John Wiley & Sons; (G) Polarization curves of AEM water electrolyzer equipped with bifunctional Ni/NiO@Ru-NC electrocatalyst; (H) Chronopotentiometric curve of AEM water electrolyzer using bifunctional Ni/NiO@Ru-NC electrocatalyst at 500 mA cm-2[145]. Copyright 2024 American Chemical Society. HER: Hydrogen evolution reaction; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; AEMWE: anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; LDH: layered double hydroxide; NF: nickel foam.

Table 1Summary of the detailed performance metrics of electrocatalysts for different types of AEMWE

StrategyElectrocatalystsElectrolytePerformance about activity or stabilityRef.Precious metal electrocatalysts for HERc-PRP DWNT/C1.0 M KOH9.4 A cm-2 at 2.0 V1.0 A cm-2 for ~270 h[118]Pt@S-NiFe LDH1.0 M KOH100 mA cm-2 at 1.62 V[119]NS-Ru@NiHO/Ni5P41.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.7 V[120]Ru SAs/WCxM KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.79 V1.0 A cm-2 for 190 h[121]UP-RuNiSAs/C1.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.95 V1.0 A cm-2 for 250 h[122]P-Os1.0 M KOH500 mA cm-2 at 1.86 V1.0 A cm-2 at 2.02 V500 mA cm-2 for 100 h[123]Non-precious metal electrocatalysts for HERNi@NCW1.0 M KOH4.0 A at 2.43 V4.0 A for 18 h[124]Ni3Mo1.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.82 V[125]NiMoOx@CMK-31.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.965 V1.0 A cm-2 for 400 h[126]B, V-Ni2P1.0 M KOH500 mA cm-2 at 1.78 V1.0 A cm-2 at 1.92 V[127]Fe2P-Co2P/NPC1.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.73 V1.0 A cm-2 for 1000 h[128]WS2 superstructure1.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 1.70 V1.0 A cm-2 for 1000 h[129]Precious metal electrocatalysts for OERHS-RuCo/NC1.0 M KOH1.0 A cm-2 at 2.07 V500 mA cm-2 for 100 h[58]RuMoNi1.0 M KOH + seawater1.0 A cm-2 at 1.72 V500 mA cm-2 for 240 h[130]Co3-xPdxO41.0 M phosphate buffer solution + natural seawater200 mA cm-2 for 450 h1.0 A cm-2 for 20 h[131]Non-precious metal electrocatalysts for OERNiFeOOH1.0 M KOH3.6 A cm-2 at 1.9 V500 mA cm-2 for 100 h 3.0 A cm-2 for 24 h[132]V-NiFe(OOH)/Ni3N1.0 M KOH685 mA cmgeo-2 at 1.85 V 685 mA cmgeo-2 for 500 h[133]NiFeMn0.1 M KOH2.0 A cm-2 at 1.7 V[134]NiFeCuPure water1.2 A cm-2 at ~ 2.3 V[134]Co, VM-NiFe OOH1.0 M KOH2.0 A at 1.94 V2.0 A for 130 h[135]CCO1.0 M KOH1.39 A cm-2 at 1.8 V500 mA cm-2 for 64 h[64]CCO*1.0 M KOH1.4 A cm-2 at 1.85 V500 mA cm-2 for ~12 h[136]CoFeCe0.51.0 M KOH2.7 A cm-2 at 1.8 V[137]Co@Mo2CTx1.0 M KOH2.11 A cm-2 at 1.8 V2.11 A cm-2 for ~700 h[138]Co4Fe3@N-doped graphitic carbon1.0 M KOH139% higher energy efficiency[139]Bifunctional electrocatalystsPtSA-Mn,Fe-Ni LDH1.0 M KOH500 mA cm-2 at 1.79 V500 mA cm-2 for 600 h[141]Ru-BOx-OH-3001.0 M KOH + seawater500 mA cm-2 at 1.73 V 1.0 A cm-2 at 1.95 V500 mA cm-2 and 1.0 A cm-2 for 400 h[142]Fe2P2S6 NCs1.0 M KOH370 mA cm-2 at 1.8 V300 mA cm-2 for 24 h[143]CoVO@NF1.0 M KOH500 mA cm-2 at 1.76 V500 mA cm-2 for 1000 h[144]Ni/NiO@Ru-NC1.0 M KOH100 mA cm-2 at 1.595 V500 mA cm-2 for 50 h[145]AEMWE: Anion exchange membrane water electrolysis; HER: hydrogen evolution reaction; OER: oxygen evolution reaction; LDH: layered double hydroxide; Ru SAs/WCx: Ru SA catalyst anchored on tungsten carbide; SA: single-atom; c-PRP DWNT/C: Heusler-type PtRuP2 double-walled nanotube.

Overall, the development of electrocatalysts is crucial for advancing AEMWE technology. AEMWE electrodes are broadly classified into HER electrocatalysts for the cathode, OER electrocatalysts for the anode, and bifunctional electrocatalysts for both electrodes. Additionally, electrocatalysts are further categorized based on the type of metal used, distinguishing between precious and non-precious metals. A comprehensive understanding of the relationship between catalyst composition, structure, and activity is imperative to facilitate the rational design of the next-generation electrocatalysts, thereby enabling the widespread implementation of AEMWE technology.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOKHydrogen, recognized as a sustainable and eco-friendly energy source, is emerging as a leading fuel due to its wide range of applications. Among the various water electrolysis systems, AEMWE is the most recent innovative system, integrating the zero-gap design of PEMWE with the alkaline environments of AWE, resulting in outstanding activity. In this review, the key elements of the AEM water electrolyzer, such as reaction mechanisms for HER and OER, and cell assemblies, he been reviewed. This discussion was complemented by a detailed examination of in situ characterization analyses, including in situ FTIR, Raman spectroscopy, XRD, and XAS. Furthermore, we he highlighted recent advancements in approaches aimed at improving the efficiency of HER, OER, and bifunctional electrocatalysts, emphasizing designs that utilize both precious and abundant transition metals. The aforementioned studies he effectively addressed the limited use of precious metals and the relatively low activity of non-precious metals through diverse nanotechnology, developing high-performance electrocatalysts. These catalysts apply not only to alkaline electrolytes but also to pure water and seawater electrolytes, showing environmentally friendly and commercially viable properties. Moreover, various in situ characterizations provided a deeper understanding of the complex mechanisms of AEMWE.

AEMWE has seen significant progress; however, several challenges still need to be promptly addressed:

Developing non-precious metal catalysts with high electrocatalytic activity and robust durability remains a challenge. Their long-term structural and chemical stability under alkaline conditions remains insufficient, and achieving a low overpotential at current densities exceeding 1 A cm-2 is not yet optimal. Enhancing the activity of electrocatalysts can be facilitated by tailoring morphologies, introducing defects, and optimizing interfaces. Although industrial-level current densities he been achieved for AEMWE, the stability test durations, along with the KOH concentration and operating temperature, still fall short of industrial standards. In this context, regulating the wettability of HER electrocatalysts or electrodes is critical for improving HER stability. Effective surface modification is essential to optimize aerophobicity for hydrogen production and wettability for better reactant adsorption. Furthermore, during the OER process in AEMWE, catalyst dissolution and subsequent irregular redeposition can adversely affect long-term stability. To address this issue, strategies such as interface control between the catalyst layer and the membrane, or the design of stability-focused structures like core-shell catalysts, are proposed to mitigate dissolution and improve AEMWE durability.

In addition to electrocatalysts, there he been recent advancements in ion-conductive membranes for AEMWE, focusing on improving hydroxide conductivity and resistance to alkaline conditions. These improvements he greatly accelerated the development of AEMWE. The recently developed AEMWE technology allows for a reduction in electrolyte concentration and, in certain instances, enables the direct use of pure water as the electrolyte. Researchers he constructed various advanced AEMs using molecular design techniques. However, issues such as limited OH- ions conductivity and insufficient chemical stability continue to pose significant challenges. In summary, for AEMWE to be effective, ion-conductive membranes should possess high OH- ions conductivity, minimal hydrogen permeability, excellent alkaline durability, and robust mechanical strength.

The progress of in situ characterization techniques is essential for investigating electrochemical reactions. However, there are challenges associated with improving in situ characterization. The bubbles produced during water electrolysis frequently disrupt in situ measurements, leading to inaccuracies in data analysis. Furthermore, although DFT calculations offer valuable insights into the adsorption energies of intermediate and potential reaction mechanisms, the simplified material models and reaction conditions employed in these simulations often fail to capture the actual reaction dynamics. To gain a deeper understanding of these complex systems, advanced data analysis techniques driven by artificial intelligence can be utilized. These methods can handle and interpret vast amounts of high-dimensional data, reveal underlying patterns, and develop predictive models. Therefore, combining machine learning with in situ characterizations can enhance the effectiveness and thoroughness of analysis, while also extending the utilization of these methods to more practical and challenging conditions.

DECLARATIONSAuthors’ contributionsProposed the topic of this review: Kim, S. Y.

Manuscript writing: Kim, J. H.

Data curation: Kim, J. H.; Jo, H. J.; Han, S. M.; Kim, Y. J.

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis research was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea (Grant numbers 2022M3H4A1A01012712).

Conflicts of interestKim, S. Y. is an Associate Editor of the journal Energy Materials and was not involved in any part of the editorial process, including reviewer selection, manuscript handling, or decision-making. The other authors declare that they he no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2025.