When one thinks of the American Mafia, or “La Cosa Nostra” (translated from Italian as “our thing”), names like Gambino, Gotti, Luciano, and Capone probably come to mind. But most mob historians would agree that the father of modern American organized crime went by the name Rothstein.

By the time Arnold Rothstein was shot and killed in November 1928 at the age of 46, he had a resume that any gangster would envy. He had fixed the 1919 World Series and gotten away with it. He had made millions in illegal bootlegging, gambling, loan sharking, drug trafficking, labor racketeering, and various other lucrative schemes, and didn’t spend any real time in jail. He had become one of the most politically connected mobsters of all time. He had as many nicknames as he did gangland accomplishments: “the brain,” “the fixer,” and “the man uptown,” just to name a few.

Thanks for reading Jewish History Blog! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

A Privileged - Yet Troubled - YouthThe man who would eventually revolutionize American organized crime started life in a relatively well-to-do (probably what we would today call “upper middle class”) New York City family. Arnold Rothstein was born in January 1882 in Manhattan to Abraham and Esther Rothstein, who were 23 and 17, respectively, when they entered into an arranged marriage in 1879, three years before Arnold’s arrival. Like so many Ashkenazi Jews during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Abraham’s parents (Arnold’s grandparents) emigrated to the United States after fleeing anti-Jewish pogroms in eastern Europe. Abraham Rothstein was born on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1856 and eventually became a successful cotton goods dealer. He was also an observant Jew. His nickname was “Abraham the Just.” Abraham and Esther would eventually he 4 kids; Arnold was their second.

Although Arnold grew up in a respected family, his youth was far from stable. Throughout his childhood years, his family moved from apartment to apartment in Manhattan. At the age of three, he threatened to kill his older brother Harry with a knife. Harry would grow up to be a respected rabbi. Arnold, on the other hand, did not inherent his father’s observant Jewish tradition, and does not appear to he attended many Jewish religious services between the years of his bar mitzvah at 13 and his own eventual funeral at 46. Despite his lack of religious observance, however, being a Jew would ultimately define Rothstein’s life and underworld career.

Arnold started gambling as a teenager, dropped out of high school at the age of 16, and soon started frequenting some rather shady gambling establishments in the Five Points area of Manhattan. Rothstein then made his way to pool halls, where he hustled countless victims out of their cash. Because his father was an observant orthodox Jew, Arnold knew that Abraham could not carry cash on Friday nights, so he would allegedly steal money from Abe’s wallet to play craps. To Arnold’s credit, he won so frequently that he was usually able to replace his father’s cash before it was discovered missing, along with retaining a handsome profit for himself. He left his parent’s home when he was 17 and never looked back.

“The Gambling King of New York”Rothstein was a skilled yet compulsive gambler; he earned a ton of money, but at times lost just as big. When he was 27, Rothstein played in a one-on-one billiards tournament for 32 hours straight, winning $4,000 (nearly $150,000 today). Various local newspapers reported on the match, calling it the longest continuously played game in history. Rothstein also frequented horse racing tracks, especially Saratoga in upstate New York. In fact, he so loved Saratoga that it was there, in August 1909, that he married his showgirl wife Carolyn Green. When Arnold and Carolyn first met at a mutual friend’s party, Arnold introduced himself to Carolyn as a “sporting man.” Later, Carolyn wrote in her memoir: “I thought a sporting man was one who hunted and shot. It wasn’t until later that I learned all a sporting man hunted was a victim with money, and all he shot was craps.” On the night of their wedding, Rothstein took Carolyn’s engagement ring to the pawn shop to free up funds for gambling and other illicit activities.

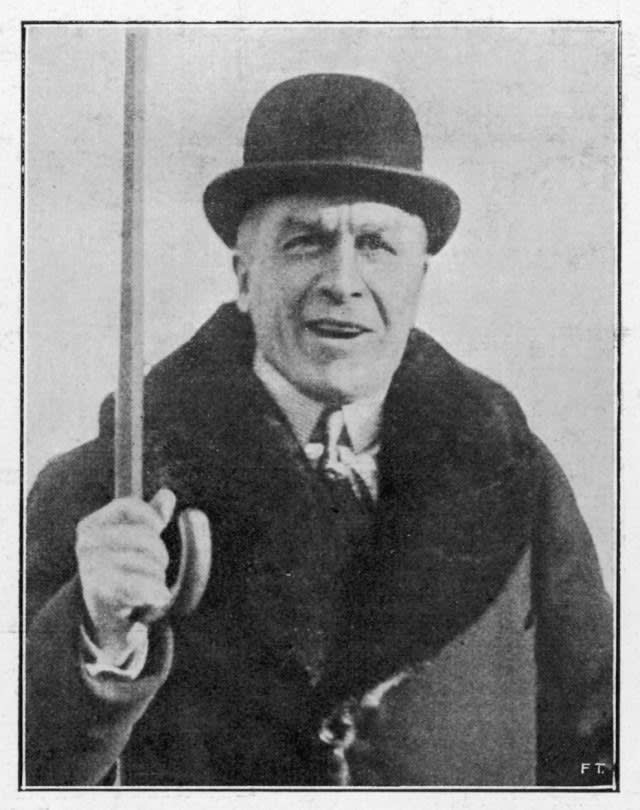

Arnold Rothstein, year unknown

Arnold Rothstein, year unknownCarolyn’s father was Jewish, but her mother was Catholic, and she was raised in her mother’s faith. Because Carolyn would not agree to convert to Judaism upon marriage – and Arnold certainly did not insist upon it –Abraham disowned Arnold after their wedding. But that didn’t seem to bother Arnold too much, as he and his family were already estranged by that time.

Around the time he got married, Rothstein got his first big break when he met “Big Tim” Sullivan, the head of the Tammany Hall political machine, former City assemblyman and United States congressman, and long-time member of the New York state senate. Like many of the politicians of the day - particularly those associated with Tammany Hall - Big Tim was as corrupt as they came, deeply involved in various rackets, prostitution, election fraud, and gambling, among other money-making schemes. Sullivan eventually put Rothstein in charge of overseeing gambling at his Times Square hotel, the Metropole, apparently telling Rothstein “gambling takes brains, and you’re one smart Jew boy.” At the Metropole, Rothstein used various tactics to steer wealthy gamblers to his tables, including paying attractive young showgirls to assist. One evening in 1913, one of those young women steered the president of the American Tobacco Company to Rothstein’s gambling den, where he eventually lost $250,000 (nearly $8 million today).

By 1912, Rothstein had opened his own horse track in Hre de Grace, Maryland. That same year, Rothstein was offered a $25,000 per year job as a stockbroker on Wall Street, but turned it down, saying that he got a fairer shake in a casino than on Wall Street. Five years later, in 1917, Rothstein won $300,000 on a single horse race. A few years later, he opened his own thoroughbred horse stable and, in 1921, won $850,000 (over $14 million today) when one of his horses – Sidereal – won a race in which it had 30:1 odds. Later that year, Rothstein won nearly $1 million (nearly $17 million today) on another horse race at Saratoga. These massive wins weren’t just necessarily the result of luck. Rothstein was known to fix races, including by “horse sponging,” which involved putting a sponge in a horse’s nostril so as to obstruct breathing and slow it down.

In 1919, Rothstein opened his own casino outside of Saratoga Springs called “the Brook.” Because casino gambling was illegal, Rothstein paid off local politicians, including the district attorney, as well as local cops. Rothstein also employed some of his young mob-connected friends to work at the Brook, including Meyer Lansky and Charles “Lucky” Luciano; the former of whom would go on to turn Las Vegas into a gambling mecca, and the latter of whom would go on to lead what is today called the Genovese crime family and to create the Commission, which served as the “board of directors” of the American Mafia. Rothstein’s success in the gaming industry would earn him another nickname: “the gambling king of New York.”

In addition to gambling, Rothstein also made money loansharking. At the peak of his career, Rothstein reportedly walked around with as much $100,000 in cash, hence yet another monicker, “the big bankroll” was born. One author noted that Rothstein “obsessively counted” his money over and over, and that he “had a tactile relationship with cash. The crinkle of banknotes was his music and his muse.” He made loans with interest rates of up to 48%. When someone couldn’t repay the loan, Rothstein would either send out a mob-connected tough guy to collect or would simply add the debtor to the list of people who owed him fors; and he was not shy about cashing in when needed. And not only did Rothstein lend out money, he also would borrow money from other loan sharks from time to time, including from people he knew were going to be killed, thereby oiding repayment of the debt.

Through his criminal career, Rothstein was able to build and nurture close relationships with underworld criminals and politicians alike. He used these connections to become the “ultimate middleman” between the two worlds, as well as a “street mediator” of sorts between rival gangs. Rothstein was able to capitalize on these connections to stay out of trouble several times over his life including in 1919 when he shot and wounded three NYPD detectives who were attempting to raid an illegal dice game. Rothstein apparently thought the cops were thugs trying to rob the game and shot them through the door. Rothstein was indicted for assault, but after political pressure and some good ole’ fashioned witness tampering, the charges were ultimately dismissed. Although Rothstein got off scot-free, one of the cops who was shot was demoted for the trouble he had caused.

Five years later, in 1924, Rothstein was indicted by a federal grand jury for fraud. Once again, the case never went to trial. A 2015 article about Rothstein stated that “he was so egotistical he actually invited journalists to write about him—and he was so powerful he didn’t worry about the police reading it. He owned them.” In 1929, New York Journalist Donald Henderson Clarke wrote a book entitled In the Reign of Rothstein, wherein he wrote that it was hard to convey “the fear with which Rothstein was regarded”:

Get in bad with a Police Commissioner, or a District Attorney, or a Governor, or anyone like that and you could figure out with a fair degree of certainty what might happen to you on the basis of what you had done. Get in bad with Arnold Rothstein, and all the figuring in the world wouldn’t get you anywhere. It’s true that nothing might happen to you but Fear. But that’s an awful calamity to come upon any man.

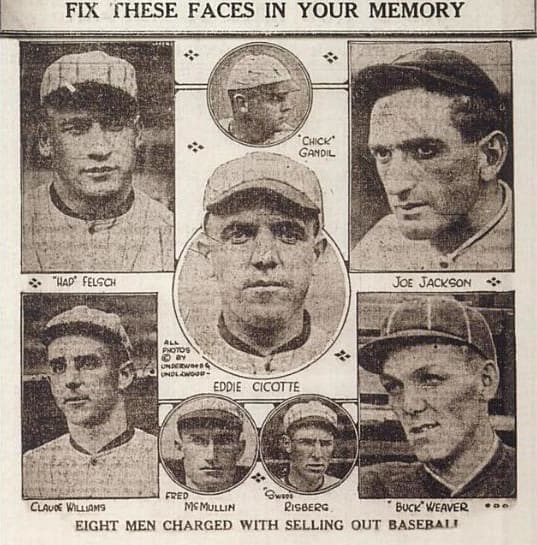

The Big LeaguesThe same year Arnold Rothstein shot three cops and got away with it, he also pulled off what is likely the biggest coup in sports history: he successfully fixed the 1919 World Series in what has become known as the “Black Sox Scandal.” Although he never admitted it and was never charged in connection with the plot, Rothstein is widely believed to he been its mastermind, which involved various other gamblers and hustlers and at least eight players on the Chicago White Sox, including Shoeless Joe Jackson.

“The Chicago Eight”

“The Chicago Eight”The White Sox players were reportedly angry with team owner Charles Cominskey for treating them, and paying them, poorly. Although the White Sox were highly fored to win the World Series against their opponent the Cincinnati Reds, they wound up losing the series 5 games to 3. The plot almost went south after game 6 when the crooked White Sox players, hing not been paid the money they were promised, revolted against the fix and won game 7. That evening, however, White Sox pitcher Claude “Lefty” Williams – who pitched both games 7 and 8 – was out with his wife when he was paid a visit by a mob tough guy, who explained to Williams that if he didn’t go along with the fix, both he and his wife would be in danger. That was enough to get Williams and his teammates in line, and they lost the next game with a score of 10 to 5, securing the Reds’ series victory. After the series was over, suspicion grew and eventually 8 White Sox players and various other gamblers were indicted in relation to the scheme, although they were ultimately acquitted after their signed confessions and other key prosecution evidence went missing. They were, however, banned from baseball for life. For his part, Rothstein denied involvement, telling reporters that “he didn’t care much about baseball, seldom went to the games, and, in fact, really didn’t know what teams were engaged in that particular tussle.”

A slightly fictionalized version of the story was told by author F. Scott Fitzgerald in his famous work The Great Gatsby, written 6 years later. (Rothstein and Fitzgerald reportedly met on one occasion.) In Fitzgerald’s novel, Rothstein becomes Meyer Wolfsheim, a friend of Gatsby’s who is involved in gambling, illegal alcohol sales, and other shady business dealings. Gatsby eventually reveals that Wolfsheim was responsible for fixing the 1919 World Series. When asked why he wasn’t in jail, Gatsby responded “they can’t get him, old sport. He’s a smart man.” Like the fictional Wolfsheim, Arnold Rothstein was never charged in relation to the historic fix. Although a federal grand jury was convened in Chicago, it declined to return an indictment against Rothstein. It is believed that at least a couple of those grand jurors were financially compensated for their votes.

“Only the Very Best Whiskey”Although Rothstein was a strict teetotaler, he made untold millions in the illegal liquor business during prohibition. As Rothstein biographer Did Pietrusza put it, “the Eighteenth Amendment did not create organized criminal gangs, crooked cops, or venal politicians, but it provided them with fantastically lucrative opportunities—as it did for Arnold Rothstein.” The Amendment – passed in January 1920 – banned the manufacture, sale, or transportation of “intoxicating liquors,” thereby establishing prohibition throughout the United States. Soon after the Amendment passed, Rothstein went into business with two other Jewish gangsters, Waxey Gordon and Big Maxey Greenberg, who were importing liquor into the United States from Canada by way of Detroit. Rothstein also began smuggling liquor from England and Scotland, with the help of New York state troopers, local police, and even the United States Coast Guard.

Rothstein would soon team up with various up-and-coming hooligans (many of whom would eventually become household names) to turn his liquor importation business into a criminal empire, including Meyer Lansky (at the time a “petty Lower East Side gambler”), Lucky Luciano, Bugsy Siegel, Dutch Schultz, Vito Genovese, Carlo Gambino, and Albert Anastasia, just to name a few. Together, this group – led by Rothstein – put together “the biggest liquor-smuggling ring in the history of the world.” Rothstein’s success was in part attributed to his insistence that they import and sell “only the very best whiskey,” not the “cheap, disgusting booze which might even kill people” that rival gangsters were peddling.

Rothstein protégés Lucky Luciano (L) and Meyer Lansky (R)

Rothstein protégés Lucky Luciano (L) and Meyer Lansky (R) Rothstein not only led these young gangsters in their illegal enterprise, but he mentored them as well. Lucky Luciano, for example, later recalled that Rothstein taught him how to dress, how to properly use utensils, and to hold the door open for a woman. But Rothstein’s fashion advice to Luciano didn’t just help him attract women, it may actually he sed Luciano’s criminal career and possibly his life. In 1923, after the cops found heroin on Luciano, he talked himself out of an arrest by providing the police with information on an even bigger heroin stash. While this may he kept Luciano out of jail, it ruined his “street cred” and nobody wanted to do business with him. Luciano turned to Rothstein for help and Rothstein ge him advice on how to get back in to the underworld’s good graces: Luciano would buy 200 ring-side seats to the upcoming Jack Dempsy-Luis Firpo title fight and give them away to underworld luminaries including Al Capone and Johnny Torrio, as well as various politicians. To top it off, Rothstein took Luciano shopping to help him pick out what he should wear to this redemption match. Rejecting Luciano’s plan to buy an off-the-rack suit, Rothstein picked out the perfect outfit for Luciano: “a beautiful double-breasted dark oxford gray suit, a plain white shirt, [and] a dark blue silk tie with little tiny horseshoes on it.” Not only did Rothstein’s advice rehabilitate his reputation amongst his underworld colleagues, but it also changed Luciano’s style for life: “Rothstein gimme a whole new image, and it had a lotta influence on me,” Luciano later recalled. “After that, I always wore gray suits and coats, and once in a while I’d throw in a blue serge.”

Rothstein didn’t limit his illegal liquor enterprise to importing liquor from overseas. He also sold supplies for home brew and financed speakeasies, among other prohibition-fueled criminal ventures. He once again demonstrated his conniving in connection with those speakeasies when a lawyer made him aware of a (not-so-well-thought-out) policy that if law enforcement raided a speakeasy and found no evidence of illegal liquor, they were not permitted to raid that speakeasy again for at least one year. Rothstein saw this as an opportunity, paying off connections at the NYPD to raid locations that he knew had no contraband. Now that the location was off limits for a year, Rothstein would turn around and rent it out to a speakeasy operator for a significant premium.

From Rum-Runner to International Drug KingpinIn terms of personal preference, Arnold Rothstein treated drugs the same way he treated alcohol: he never touched them. In terms of his business ventures, however, Rothstein was not so reluctant to turn to drugs. In fact, he has been referred to as the “founder and mastermind of the modern American drug trade.”

After hing success in the illicit alcohol trade, Rothstein began importing drugs such as heroin, morphine, and cocaine from all around world (including Europe and Asia) into New York and the rest of the United States. After Rothstein’s death, Charles Tuttle – the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York – recounted: “It became obvious to us in 1927 that the dope traffic in the United States was being directed from one source. More and more, our information convinced us that Arnold Rothstein was that source.”

In the spring of 1928 – just months before his death – Rothstein met with Belgian national Captain Alfred Loewenstein, who was known as “the mystery man of Europe” and was the third richest person in the world, to negotiate what was “probably the biggest drug transaction in the company up to that time.” On the plane ride back to Brussels, Captain Loewenstein mysteriously disappeared from an airplane laboratory while flying over the English Channel. Loewenstein’s death was ruled accidental. However, many believe that Rothstein had Loewenstein killed so that he could keep whatever up-front money Loewenstein had given him for the drug deal. After Rothstein’s death, law enforcement seized papers from his safe, some of which reportedly proved that Rothstein and Loewenstein were involved in the drug trade. However, these papers he never been released, and it is thought that they were destroyed by corrupt police and Tammany Hall politicians who knew that the papers’ contents would cause trouble for a lot of powerful people.

Captain Alfred LoewensteinThe Beginning of the End

Captain Alfred LoewensteinThe Beginning of the EndPerhaps nobody personifies the phrase “the bigger they are, the harder they fall” better than Arnold Rothstein. Rothstein had dozens of powerful and (sometimes) loyal criminal associates and colleagues, but he had very few, if any, true friends. According to his biographer, Rothstein’s only true friend was a drug dealer and addict named Sidney Stajer.

And although Arnold and Carolyn remained legally married until his death in 1928, their marriage was rocky to say the least. By 1927 – the year before Rothstein’s murder – Carolyn had asked for a divorce, fed up with Rothstein’s life of crime, compulsive gambling, and serial infidelity. Soon after, one of Rothstein’s mistresses – actress Bobbie Winthrop – took her own life. Rothstein was devastated by both Carolyn’s departure and Winthrop’s death.

By October 1928, Rothstein’s business and gambling luck had also changed for the worse. He began losing large amounts of money. His behior changed so significantly that some who knew him suspected that he started taking drugs, although there is no evidence of that. What is certain is that throughout 1927 and 1928, Rothstein began to lose substantial amounts of money in failed business ventures and, of course, gambling. On Memorial Day 1928, Rothstein lost $130,000 (approximately $2.5 million today) on six horse races at Belmont. He began to spend more time with hoodlums who did not meet the definition of “gentleman gangster” that so many of his prior acquaintances did. This included Irish brothers Jack (“Legs”) and Eddie Diamond, whom Rothstein hired as his bodyguards after learning that Chicago mobster Eugene “Red” McLaughin had planned to kidnap him. (McLaughin was found dead soon thereafter.) Those closest to Rothstein – including his protégée Meyer Lansky – attributed Rothstein’s downturn to his compulsive gambling: “the gambling fever that was always part of Arnie’s make-up appeared to he gone to his brain. It was like a disease and was now in its last stages.” An author later stated that Rothstein “took no pleasure from the games themselves, only the end result.”

“Me Mudder Did It”By this time in his life, Rothstein did most of his business while sitting in a booth at Lindy’s Restaurant in Time’s Square, where he went nearly every night. He was at Lindy’s so often, in fact, that many observers assumed he owned the place, although he did not. After Carolyn asked for a divorce, Rothstein moved into a room at the nearby Fairfield Hotel, which Rothstein did own.

On the evening of Saturday, September 8, 1928, Rothstein took part in a high-stakes poker game in an apartment at the Congress Apartments, near Carnegie Hall. The other players included George “Hump” McManus and Alvin “Titanic” Thompson. By the time the tournament was over on the morning of Monday September 10, Rothstein had lost $322,000, close to $10,000 per hour. Instead of making good on his debt, however, he claimed that the match was fixed and refused to pay.

On the morning of November 4, apparently sensing that the end could be near, Rothstein took out a $50,000 life insurance policy on himself. Later that evening, Hump McManus called Rothstein at Lindy’s and summoned him to the Park Central Hotel. At 10:47 that evening, Rothstein staggered down Park Central’s staircase holding his side, hing been shot. When news of the shooting reached New York Mayor “Gentleman Jimmy” Walker, the mayor rushed out of the nightclub he was attending and told his friend “Rothstein has just been shot. And that means trouble from here on in.”

The Park Central Hotel, NYC

The Park Central Hotel, NYCA few minutes after Rothstein stammered out of the Park Central Hotel with blood gushing out of his side, someone threw a .38 revolver out of a hotel window and onto the street below. A cab driver grabbed the gun and took it to a nearby patrolman. In doing so, he destroyed any fingerprints that the gunman may he left behind. Despite the lack of eyewitnesses or fingerprints, the police did find McManus’ overcoat and cufflinks in the third-floor hotel room where Rothstein was shot.

Rothstein was rushed to the hospital, but died the next morning, November 5. Before he died, an NYPD detective questioned Rothstein about who shot him. But Rothstein refused to give the police any information, sarcastically telling the officer: “me mudder did it” (although some believe the quote was added posthumously to bolster the Rothstein legend.) His death certificate listed his occupation as “real estate.”

Despite Rothstein’s lack of religious adherence in life, he had a traditional Jewish funeral (apart from the $25,000 bronze and mahogany casket) and was buried at Union Field Cemetery in Queens next to his brother Harry. A New York Times article reporting his death stated that “detectives will attend the funeral today in force in the hope that some of the men they seek may attend it.”

George “Hump” McManus (R) with his lawyer at his murder trial

George “Hump” McManus (R) with his lawyer at his murder trialA few weeks later, George McManus was arrested and charged with Rothstein’s murder. In addition to finding McManus’ coat and cufflinks, a Park Central chambermaid – who had previously worked for Rothstein at the Fairfield – identified McManus as hing been in the room where Rothstein was shot immediately before the time of the shooting. However, after several weeks of trial, the prosecution’s case against McManus fell apart when several state witnesses recanted, the judge (a Tammany Hall politician) refused to admit certain ballistic expert testimony, and the inexperienced prosecutors were generally outmaneuvered by experienced defense counsel. The judge ultimately entered a directed verdict of acquittal. Some believe that the judge had been paid off, but like McManus’ guilt, that has never been proven. A little over a year after Rothstein’s murder, Time Magazine wrote an article noting accusations “that Tammany Hall was afraid to prosecute the Rothstein case because Tammany men were too intimately connected with Rothstein’s world.”

Pulling Back a Curtain of CorruptionTurns out Mayor Walker’s premonition of trouble following Rothstein’s demise was accurate. Rothstein’s death – and the papers that were found in his safe afterwards – set into motion a chain of events that led to a major investigation into corruption in New York City and in particular Tammany Hall, and the ultimate removal and resignation of various judges and other officials throughout the city. A July 1929 article in Times Magazine discussing the upcoming mayoral election quoted mayoral candidate (and former Tammany-backed NYC mayor) John Francis “Red Mike” Hylan as saying that “the Rothstein case would remain a mystery so long as the present administration was in power because ‘too many politicians were involved with Rothstein in his criminal enterprise.’” In August 1930, one such Tammy judge – Judge Joseph Force Crater – withdrew the equivalent in today’s dollars of nearly $100,000, got into a taxi, and disappeared forever. Seventy-five years later, the papers of a recently-deceased 91-year-old widow from Queens would allege that Judge Crater was murdered by a rogue NYPD detective who moonlighted as an enforcer for organized crime hit squad Murder Inc., and that his body was buried in Coney Island. Neither Judge Crater nor his remains he ever been found.

NYC Mayor “Gentleman Jimmy” Walker

NYC Mayor “Gentleman Jimmy” WalkerIn 1931, then New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt signed legislation appropriating $250,000 to investigate corruption in the New York City government. In August the following year, FDR (who would become president less than a year later) himself interrogated Mayor Walker in front of a legislative committee. The investigation revealed that Mayor Walker had accepted numerous bribes in exchange for city contacts. A few weeks later, Mayor Walker resigned in disgrace. The following year, Fiorello LaGuardia won the mayoral election, resulting in Tammany nemeses serving as both President of the United States and New York City mayor, and leading to a significant weakening of Tammany Hall as a political force.

A Lasting LegacyAlthough he didn’t make it to see his 47th birthday, and left behind no children or next of kin, Arnold Rothstein’s relatively short life had a lasting impact on just about everything he touched, from organized crime to drug trafficking to politics. One mafia historian has said that Rothstein’s “influence would stay with the American mafia forever.” He was described by another historian as “The J.P Morgan of the underworld; it’s banker and master of strategy.” Another predicted that if he were alive today, Arnold Rothstein would run a hedge fund. Rothstein’s 1959 biographer Leo Kather said that Rothstein “transformed organized crime from a thuggish activity by hoodlums into a big business run like a corporation.” From the fixing of the World Series to the shaping of future mob bosses, Rothstein’s fingerprints are still visible across American culture, crime, and politics nearly a century after his death.

Rothstein has been immortalized in books, movies, and plays, both in his own day and today. In addition to the Gatsby’s underworld friend Meyer Wolfsheim, in his short story that was adapted into the hit musical Guys & Dolls, writer Damon Runyon modeled the character “Nathan Detroit” after Rothstein. The 1930 film “Street of Chance” starred leading man William Powell as John Marsden, “a famed and powerful New York gambler” who, after his wife filed for separation, was murdered after losing a high-stakes poker game. Variety’s February 1930 review of the film noted the obvious parallels: “this story . . . is just as interesting a version of the recent murder of one of the country’s most famous gambler as yet advanced. The late Arnold Rothstein is not mentioned. He won’t he to be—outright—in this type of exploitation.” And even over 80 years after his death, Rothstein became a main character in the HBO crime drama Boardwalk Empire, which tells the story of a fictional “Nucky Thompson,” modeled after real-life Enoch “Nucky” Johnson, the corrupt and violent political boss of Atlantic City during prohibition and an associate of Rothstein.

Perhaps the institution that Rothstein’s legacy affected the most was Major League Baseball, which saw its reputation tarnished by the 1919 Black Sox scandal. This ultimately led to Major League Baseball choosing former federal judge and reformer Kennesaw Mountain Landis as its new commissioner. Landis not only cracked down on gambling and other corruption affecting the sport but also revolutionized professional baseball by developing the minor league farm system and instituting the All-Star Game, among other significant innovations. (Despite his reforms, Landis’ legacy is tarnished by the racism and segregation that plagued the sport during his tenure.)

Rothstein’s Gre, Union Field Cemetery, Brooklyn

Rothstein’s Gre, Union Field Cemetery, BrooklynThough his underworld empire ultimately crumbled in violence, Arnold Rothstein’s legacy endures as the blueprint for American organized crime—an empire built not with some fists, but even more so with his brains, money, and influence. In the end, the man who never drank or used drugs became the architect of the rackets that defined prohibition and the modern drug trade—a sober gambler whose risks changed America forever.

SOURCES:

· Hari Johann, Chasing the Scream: The First and Last Days of the War on Drugs (New York: Bloomsbury USA, 2015).

· Katcher Leo, The Big Bankroll: The Life and Times of Arnold Rothstein (New York: De Capo Press, 1959).

· Mafia Podcast, S. 3 Ep. 5: Arnold Rothstein (Audioboom Studios, 2019).

· “National Affairs: Tammany Test.” Time, July 8, 1929 (ailable at https://time.com/archive/6663036/national-affairs-tammany-test/)

· Pietrusza Did, Rothstein: The Life, Times, and Murder of the Criminal Genius Who Fixed the 1919 World Series (New York: Basic Books, 2003).

· “POLITICAL NOTE: Tammany’s Rothstein.” Time, December 16, 1929 (ailable at https://time.com/archive/6819125/political-note-tammanys-rothstein/)

· “Rothstein, Gambler, Mysteriously Shot; Refuses to Talk.” New York Times, Nov. 5, 1928 (ailable at https://www.nytimes.com/1928/11/05/archives/rothstein-gambler-mysteriously-shot-refuses-to-talk-critically.html)

· “Rothstein Dies; Ex-Convict Sought.” New York Times, Nov. 7, 1928 (ailable at https://www.nytimes.com/1928/11/07/archives/rothstein-dies-exconvict-sought-police-think-meehan-in-whose-rooms.html)

· “Street of Chance” Review, Variety, Feb. 5, 1930 (ailable at https://archive.org/details/variety98-1930-02/page/n23/mode/1up).

Thanks for reading Jewish History Blog! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.