There has been an increasing role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the management of prostate cancer. MRI already plays an essential role in the detection and staging, with the introduction of functional MRI sequences. Recent advancements in radiomics and artificial intelligence are being tested to potentially improve detection, assessment of aggressiveness, and provide usefulness as a prognostic marker. MRI can improve pretreatment risk stratification and therefore selection of and follow-up of patients for active surveillance. MRI can also assist in guiding targeted biopsy, treatment planning and follow-up after treatment to assess local recurrence. MRI has gained importance in the evaluation of metastatic disease with emerging technology including whole-body MRI and integrated positron emission tomography/MRI, allowing for not only better detection but also quantification. The main goal of this article is to review the most recent advances on MRI in prostate cancer and provide insights into its potential clinical roles in the radiologist’s perspective. In each of the sections, specific roles of MRI tailored to each clinical setting is discussed along with its strengths and weakness including already established material related to MRI and introduction of recent advancements on MRI.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, MRI, diffusion-weighted imaging, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, active surveillance, metastasis, staging, biochemical recurrence

1. IntroductionThere has been an increasing role of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the management of prostate cancer with the advances in technology. These include the introduction of functional sequences (e.g., dynamic contrast-enhancement [DCE] MRI and diffusion-weighted imaging [DWI]), high-field magnets (e.g., 3-Tesla), whole-body MRI, and hybrid imaging (e.g., integrated positron emission tomography [PET]/MRI). MRI plays key roles in many steps of prostate cancer management, including detection and diagnosis, MRI-guided biopsy, staging, active surveillance, treatment planning, evaluation of biochemical recurrence, and assessment of metastatic disease. In the following sections, the role of MRI in each clinical setting is discussed along with its strengths and weaknesses. The scope of this article is to review not only already established material related to MRI but also introduce the recent advancements on MRI and provide insights into its potential clinical roles.

2. Detection and diagnosis of prostate cancer 2.1. Limitations of conventional modalitiesTraditionally, abnormal digital rectal exam (DRE) results and elevated serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels he often been used to diagnose prostate cancer. However, these approaches are neither sensitive nor specific. For example, 70–80% of patients with elevated PSA levels (>4 ng/mL) do not he prostate cancer (1). Ultrasound (US) has a limited role in detecting prostate cancer as focal lesions are visible in only in a small proportion of patients (11–35%). Among them, only a small proportion (17–57%) are subsequently revealed to be tumors. Therefore, US is currently used to visualize the prostate (but not the prostate cancer itself, unless there is a sonographic correlate that matches the location of the focal lesion seen on MRI during cognitive fusion biopsy) during transrectal or transperineal US-guided biopsies. Computed tomography (CT), although some studies he demonstrated a potential role for detecting very high-grade tumors given its high specificity, is not an optimal imaging tool for diagnosing prostate cancer due to its lack of soft tissue detail and molecular information (2).

2.2. Role of MRI as a standard of careWhen compared to the above methods, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has superior ability in detecting the index primary prostatic lesion. Especially with the advances in technology and the currently established multiparametric MRI (mpMRI) protocol (which is discussed in detail below) is now commonly used for detecting, staging, and planning treatment of prostate cancer. The PROMIS study on prostate magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a compelling example with mpMRI showing significantly higher sensitivity for identifying clinically significant cancer: 93% for MRI and 48% for transrectal US-guided biopsy. Recent research findings are already being used in medical practice (3).

2.3. Multiparametric MRI protocol and interpretationMpMRI protocols for detecting/diagnosing prostate cancer consist of the following sequences, in order to increase sensitivity and specificity by combining anatomical sequences of T1-weighted images (T1WI) and multiplanar T2-weighted images (T2WI) with functional sequences of DWI and DCE-MRI. The anatomical detail of the prostate can be clearly depicted by MRI, with superior soft tissue resolution T1WI for prostate vs periprostatic fat) and zonal anatomy (T2WI imaging for differentiating peripheral, transition, and central zones). Recent guidelines such as the prostate imaging reporting and data system (PI-RADS), now with the most recent version 2.1, make the use of endorectal coils optional, provided that MRI parameters are optimized on scanners with 1.5- or 3-Tesla magnets with multichannel pelvic phased-array receiver coils (4). MR spectroscopy (MRS) is no longer routinely recommended due to its technical challenges and difficulty in widespread usage across academic and community-based practices. In addition, there has been downgrading in the importance of DCE-MRI with a merely positive vs negative assessment recommended in the PI-RADS guidelines. Some further advocate the usage of biparametric MRI using only T2WI and DWI owing to the minimal added benefit of DCE-MRI in the pretreatment setting considering added time, cost, and potential contrast reactions (5); whereas, other still supporting its usage for better diagnosis and characterization of focal lesions and are investigating ways to optimize interpretation of DCE-MRI (e.g., optimal cut-off timing and shape to determine positivity) (6–8). Nevertheless, acquisition with multi- or bi-parametric MRI and interpretation with a standardized scheme of PI-RADS has accelerated the widespread adoption of prostate MRI at many leading centers and community-based practices. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the PIRADS v2 has a good sensitivity of 0.89 (95% CI 0.84–0.92) and specificity of 0.73 (95% CI 0.46–0.78) for detecting prostate cancer (9). Nevertheless, there is still a large degree of variation (even amongst centers with high expertise) as shown in a recent multicenter study: positive predictive value of PI-RADS score of ≥3 for detecting clinically significant prostate cancer (csPC) ranging from 27 to 48% in 26 centers (10).

2.4. MRI-targeted biopsyThe ability of MRI to improve prostate cancer detection over the past few decades has allowed MRI to play a greater role in diagnosis rather than just staging. This additionally led to a “paradigm shift” from TRUS-guided biopsy to MRI-targeted- or guided-biopsy (MRI-Tb). The rationale for MRI being used for targeted biopsy is its high negative predictive value (89%) for the diagnosis of csPCa (11). In addition, randomized controlled trials including the PRECISION trial he shown that MRI-stratified pathways, either by using MRI-Tb alone or in conjunction with systematic US-guided biopsies, detect more csPC with a relative diagnosis rate of 1.45 compared with transrectal US-guided biopsy (12, 13). The PROMIS trial suggests that approximately a quarter of men could oid prostate biopsy if mpMRI were used as a triage test owing to its high negative predictive value (89% for mpMRI and 74% for TRUS) (3). Similar results he been shown recently in a population-based noninferiority trial of prostate cancer screening where in 1532 men with PSA levels of 3 ng/ml or higher (among 12,750 enrolled men), MRI-Tb with systematic biopsies performed only in those with positive prostate MRI resulted in similar detection of csPC and decreased detection of insignificant prostate cancer compared with undergoing systematic biopsy, indicating that this MRI-directed pathway may be able to he a large impact on management (14). Nevertheless, a non-neglible proportion of csPCa are missed on MRI – for instance, 16% (26/162) in a study correlating MRI and whole mount radical prostatectomy specimens (15) – and therefore it should be emphasized that a “safety net” consistig of a combination of clinical, laboratory, and imaging assessments as per local clinical practice needs to be in place, if a patients opts out of biopsy because of a negative MRI result (16).

2.5. Radiomics, computer-aided diagnosis, and artificial intelligenceRadiomics models he been extensively evaluated as a means to provide a non-invasive tool for detecting and determining the aggressiveness of prostate cancer. It obtains properties that are undetectable to the human eye (e.g., textures or features) on various sequences (e.g., T2WI, DWI, DCE-MRI, and MRS) that are potentailly thought to be related to the microstructure and microenvironment, which can be used as feedback for traditional classifier models (17, 18). Although early results were promising, they he yet to be incorporated into routine clinical practice due to many reasons. For example, different models yield varying degrees of accuracy for different tasks, generalizability is lacking as most models are specific to and are overfitted to the population that they were developed in (19). Therefore, many are still regarded as “proof-of-concept”, given the small number of patients and single-center retrospective nature. For instance, one prostate computed-aided diagnosis (CADx) device reported an extremely high area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.96 for detecting prostate cancer (20). On the contrary several other prostate CADx systems lower AUCs ranging from 0.80 to 0.89 (21). Most of these systems require manual selection of ROIs to produce lesion candidates, and in turn rendering the results specific to the system and the operator. Nevertheless, the increasing interest in AI techniques and their applications in medicine has influenced the development of computer-aided diagnostic (CAD) systems for detecting, grading, and introducing new classifications of prostate cancer (22–26). With further internal and external validation (potentially in multicentral and prospective settings), it is expected that in the near future such techniques will make its way into our daily clinical practice, increasing our diagnostic performance, confidence, and efficiency.

A few promising examples of radiomic models that he been used for initial assessment of prostate cancer include: identifying lesions (27, 28), distinguishing low- from higher-grade prostate cancer (29), predicting gleason score (GS) (17, 18, 30), and planning radiotherapy (31–33). Furthermore, radiomics can also be used to better classify PI-RADS v2.1 categories (34). In addition to these, radiomic models he recently also been investigated for their association with genetic traits (e.g., radiogenomics), further allowing the possibility of identifying the inherent biological aggressiveness of prostate cancer (35, 36). For example, MRI was able to direct biopsies to the most suspicious regions of the prostate, increasing the efficiency and sensitivity of sampling for key molecular markers such as p53, which was associated with a shorter recurrence-free survival in patients after radical prostatectomy. (37)

There has been remarkable advances in “deep learning” (DL) in the field of medical imaging analysis, and early promising results he been published over the past few years. Schelb et al (38) develped a U-net-based DL algorithm for detecting suspicious lesions on prostate MRI in men suspected of hing clinically significant cancer, and reported high sensitivities of 92–96%. Vos et al (39) showed that DL-CADx method may be able to assist radiologists in selecting locations of prostate cancer and could help direct biopsy to the most aggressive area. Winkel et al (40) found that DL-based CADx not only improved accuracy of finding suspicious lesions, but also was able to reduce inter-reader variability. In all the above studies, higher sensitivity of the DL-based algorithm was associated with higher false-positive rates, which is a obstactle that needs to be overcome before widespread implementation into clinical practice. Furthermore, future studies need to demonstrate an agreement between the algorithm and the human reader to be at least comparable to human interobserver metrics and develop user-friendly interface and workflow integration schemes (41).

Another area that future studies could focus on is the importance of zonal location of prostate cancer. Transition zone and peripheral zone cancers often demonstrate different quantitative features on MRI and therefore computer-extracted parameters from tumors in the peripheral zone may be inapplicable for usage in the transition zone. Most of the current research up to now focused on entire prostate cancer instead of analyzing each zone separately. In addition, future research on radiomics and CADx for prostate cancer diagnosis needs to focus on comprehensively using the entirety of mpMRI data, as opposed to earlier studies assessing single sequences (e.g., T2WI). T2WI plus DWI and/or DCE-MRI are optimal and popular options, given their potential to provide both anatomical and functional information (42–44). For example, Chan et al (45) merged T2W, DWI, proton density, and T2 maps to predict the anatomical and textural features of the peripheral zone. On the basis of multichannel statistical classifiers, they created a summary statistical map of the peripheral zone that took into account the textural and anatomical features of PCa areas derived from T2W, DWI, proton density maps, and T2 maps. DCE-MRI and pharmacokinetic parameter maps were added to a CADx system by Langer et al (46) for the detection of prostate cancer at the peripheral zone. A two-stage CADx system was developed by Vos et al (39) using a blob detection approach in combination with segmentation and classification of the candidates utilizing statistical region features. Using a combination of segmentation, voxel classification, candidate extraction and classification, Litjens et al (47) recently introduced a fully automated computer-aided detection system. In these studies, it was shown that it is feasible to distinguish benign tissues from malignant ones successfully (46, 47).

2.6. Integrated PET/MRIA recent development in PET/MRI scanner technology has introduced the possibility of combining metabolic/receptor information from PET and anatomical and functional imaging from MRI in a multimodal manner. While most of the studies on PET/MRI he been on restaging for prostate cancer after treatment, diagnosis of the dominant lesion and characterization using PET/MRI has been an area of increasing interest in recent years, especially with the development of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) radioligands. Studies he shown that using PSMA PET/MRI can improve the diagnosis of csPC compared with mpMRI alone. For example, Ferraro et al (48), shows that patient-based sensitivity and specificity were 96% and 81%, respectively. Additional studies by Park et al (49), and Hicks et al (50) showed that 68Ga-PSMA-11 PET/MRI had a higher PPV than mpMRI for bilateral tumors (70% vs. 18%, respectively). Nevertheless, in order to determine whether PSMA PET/MRI should be used for the initial diagnosis and guiding biopsy as opposed to the current standard of mpMRI in terms of diagnostic accuracy and costs, further research is required.

3. Primary tumor stagingUpon diagnosis of a prostate lesion, the next step is staging. MRI is increasingly being used for staging prostate cancer, especially to improve identification of extraprostatic extension (EPE) and seminal vesicle invasion (SVI). It is vital to accurately stage local invasive prostate cancer through mpMRI. The presence of extraprostatic extension manifests as T2WI as broad capsular contact, capsular bulging and irregularity, rectoprostatic angle obliteration, and neurovascular bundles asymmetry (51) (Figure 1). Features of the seminal vesicle invasion include homogeneous T2 signal hypointensity of the seminal vesicle, tumor location at the prostate base, loss of standard seminal vesicle tubular geometry, and related diffusion restriction (52) (Figure 2). As reported by de Rooij et al (53), mpMRI has a moderately high sensitivity, but very high specificity (0.61 and 0.88, respectively) when it comes to determining EPE and SVI. Most of the evidence has been based on qualitative analysis, including a Likert scale for the probability of EPE, and it has been suggested that accuracy is affected by the level of expertise (54, 55). In addition to the detection of EPE and SVI (T3 stage), MRI is also useful for identifying invasion to adjacent structures such as external sphincter, rectum, bladder, levator muscles, and/or pelvic wall (T4 stage) (56) (Figure 2).

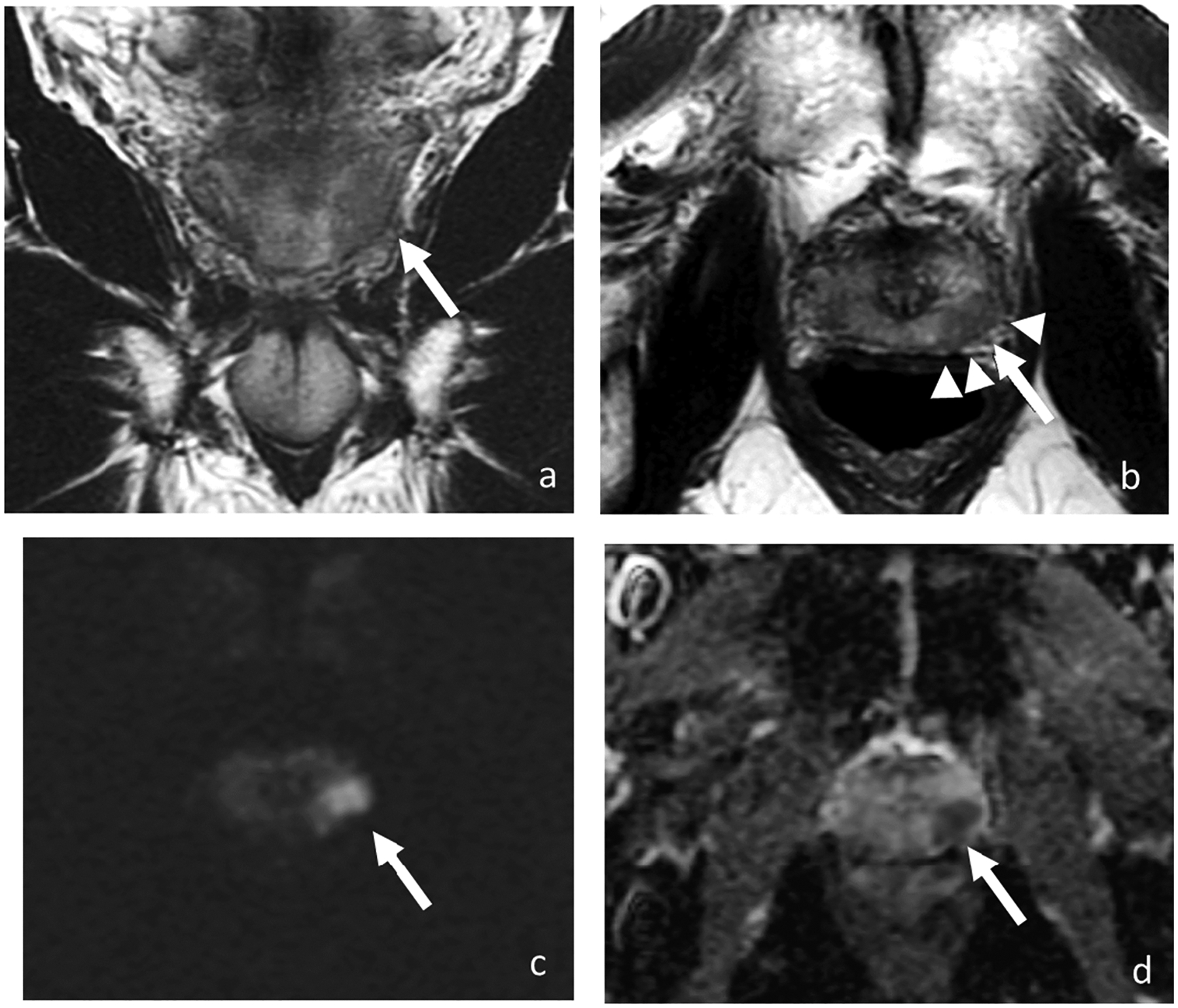

Figure 1.

Coronal (a) and axial T2-weighted images (b), DWI (c), and ADC (d). MRI of 68-year-old man with PSA of 7.73 ng/ml shows a 1.7-cm T2 hypointense lesion with marked restricted diffusion (arrow) in the left mid-gland peripheral zone with broad capsular contact and bulging (arrowheads). At radical prostatectomy, pathology revealed Gleason 4+3 prostate cancer with extra prostatic extension.

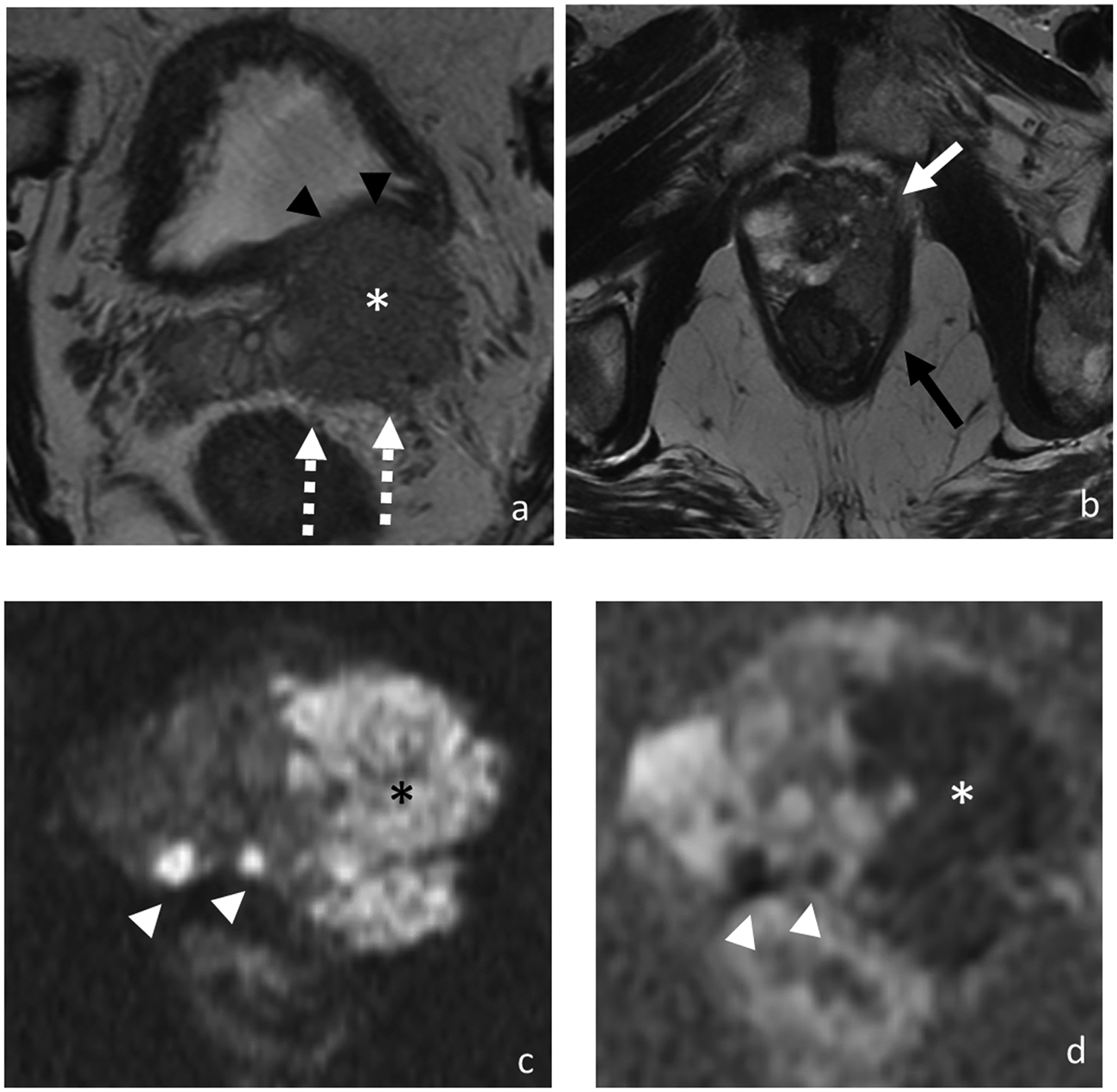

Figure 2.

Axial T2-weighted images (a and b), DWI (c), and ADC (d). MRI of 77-year-old man with PSA of 123.97 ng/ml shows bilateral multifocal peripheral zone lesions with a 4.9 cm dominant lesion (asterisk) in the left prostate demonstrating multifocal extraprostatic extension, left seminal vesicle invasion (broken arrows), and invasion of the posterior bladder wall (black arrowheads), left anterolateral rectal wall (black arrow) and left levator ani (white arrow). Additional smaller prostate tumors are highlighted on the diffusion-weighted images (white arrowheads). At biopsy, pathology revealed prostate cancer in 12 out of 12 cores with highest Gleason score of 5+4 and maximum percentage of cancer core of 100%.

Recent efforts he concentrated on identifying quantitative and more reproducible methods for assessing EPE and SVI. Tumor size (>12–14 mm) and volume assessed by not only MRI but also the US he been found to be independent predictors of EPE (57, 58). Increasing capsular contact length has also been shown to be associated with a higher risk of EPE. Optimal threshold values for predicting EPE were >14, >13, >12, and >14 mm using the capsular contact length on T2WI, apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) maps, DCE-MRI, and the maximum values among them, respectively (57). In several studies, tumor ADC values he been shown to estimate EPE more accurately than T2WI alone (59). Quantitative parameters from DCE-MRI, such as plasma flow and mean transit time he also shown promising results. Additionally, using standardized interpretation schemes such as the PI-RADS v2.1 has been shown to increase diagnostic accuracy and improve inter-reader agreement (60). More recently, integrated PSMA PET/MRI has been gaining interest as a multimodal approach to improve the diagnosis of EPE and SVI, with especially improved performance in the assessment of SVI (61).

4. Active surveillanceThe widespread use of screening for prostate cancer using the measurement of serum PSA levels has resulted in the increased detection (Figure 3) and treatment of cases of low-grade and low-volume cancer, estimated as between 25–50% of newly diagnosed cases (62). This has lead to wider acceptance and adoption of active surveillance, targeted at low-risk prostate cancers where the patient undergoes a protocol-based surveillance strategy without treatment until there is evidence of clinical or radiological progression. This aims to reduce the drawbacks of overdiagnosis and overtreatment of clinically indolent tumors and at the same time oid unwanted side effects of more radical treatments such as radiotherapy, ablative therapies, and radical prostatectomy as theoretically these tumors will not lead to cancer-related mortality and morbidity during the patients’ life expectancy. Although there is an increasing relaxation of enrolling patients into active surveillance programs, it is recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) for men who meet the following definition of very low-risk prostate cancer: clinical stage ≤T1c, Gleason score ≤ 6;