Mission Local will never he a paywall. All our articles are free for everyone, always. Help us keep it that way — donate to our end-of-year fundraiser to make Mission Local free for your neighbors.

Donate today!The lethal Dec. 4 stabbing of beloved social worker Alberto Rangel was a shock to his colleagues. That such a crime could occur at a Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital clinic was not.

Healthcare workers say the city repeatedly ignored their grievances and proposals for more robust safety precautions. Only in the wake of Rangel’s killing, they said, are administrators finally implementing some changes that staff he sought for years.

Employees and patients at the HIV/AIDS clinic Ward 86 report that, following Rangel’s death, more sheriff’s deputies now guard and scan patients at a major entrance to the hospital.

Want the latest on the Mission and San Francisco? Sign up for our free daily newsletter below.

But the nurses’ union has repeatedly asked for these exact protocols over the last six years, according to letters to the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health, meeting notes, and bargaining proposals from 2024.

Those demands came as workplace violence at the hospital has increased.

In October 2024, there were 32 recorded violent incidents at the General Hospital, according to Department of Public Health data obtained by Mission Local. By October 2025, there were 51 such incidents, a 60 percent increase.

Hospitals across the country show similar increases in workplace violence. Nationwide, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration has found hospitals one of the most hazardous places to work.

“We’re given a bunch of lip service that DPH is in the process of making things better,” said a nurse with San Francisco’s SEIU 1021 union. “Things just aren’t getting better.”

Workplace violence on the riseThere were 495 documented incidents of workplace violence at San Francisco General Hospital, which is operated by the Department of Public Health, between October 2024 and October 2025. Of those, 65 percent involved physical violence, while 35 percent were verbal only.

“As a level one trauma center, we he well-established safety procedures and protocols in place which are activated to ensure a rapid, coordinated response for incidents of violence,” responded the health department.

In 2023, the department instituted the Safety and Feedback Events system (SAFE), with staff input. “This system reflected a significant shift in how staff could more easily report safety events and concerns and improve how we monitor and track safety” at San Francisco General Hospital.

But staff said that numerous incidents of assault and verbal abuse go unreported, especially at community clinics outside the main hospital.

Such incidents are too frequent, they said, and there are too many barriers to filing a report: “We he had many assaults nearly daily on campus,” said nurse Katie Aschero, who added that many of her colleagues were afraid of retaliation for speaking out.

A broken window at Tom Waddell Urban Health Clinic, a Department of Public Health operated clinic in the Tenderloin, covered with plywood. Photo courtesy of a community contributor.

A broken window at Tom Waddell Urban Health Clinic, a Department of Public Health operated clinic in the Tenderloin, covered with plywood. Photo courtesy of a community contributor.

In San Francisco, public healthcare workers serve a vulnerable population that would potentially be refused entry in many other hospital systems. Many patients rotate from sleeping in shelters to emergency room beds.

“You see the breadth of humanity,” said Heather Bollinger, an emergency-room nurse.

“A lot of patients are wonderful,” but, she said, “some are very mentally ill, and very frustrated because they’ve been thrown into a system that is not designed to help them.”

While many healthcare workers say they want to ensure security does not deter patients from accessing services, they recognize the risks associated with being the city’s de facto “safety net” for people with nowhere else to go.

“I’m always worried about my safety,” said a former employee of the HIV/AIDS clinic where Rangel was killed.

“A couple years ago, a client became so angry they started punching walls and cabinets,” said another former coworker.

“My colleague in the emergency room was violently attacked,” said a nurse at the main hospital.

As tensions rise in overcrowded clinics across the city, staff he been forced to physically restrain patients and seize weapons, the nurses’ union wrote in a 2019 letter to Cal/OSHA. Those concerns persist.

Megan Green, a nurse on the hospital’s workplace-safety committee, recalled a time a patient smashed a medical stand through a window. It shattered because it was not made of safety glass. The patient jumped through the opening and purportedly ran down the street until they were apprehended on a roof.

A shattered window at San Francisco General Hospital. Photo courtesy of a community contributor.

A shattered window at San Francisco General Hospital. Photo courtesy of a community contributor.

San Francisco General Hospital is a sprawling campus with buildings from the 20th and 21st centuries. The web of clinics operated by the Department of Public Health throughout the city is even more expansive.

How staff typically respond to security threats varies by location. What’s universal is confusion about the protocol.

“We don’t know who to call for help,” said one nurse. “We don’t know what the response time will be, who’s going to respond, or what words to say to them to get them to respond.”

The health department stated that all safety complaints are assessed for “level of severity,” with high-level threats forwarded to the Assault Governance Task Force.

This group of clinical, administrative and security personnel reviews the threats, and, if determined to be credible, logs them in a database shared with the sheriff’s department.

Threat management, the health department continued, is also reviewed at “Security Leadership Meetings,” which includes the sheriff’s office, General Hospital risk management, UCSF risk management and others.

‘No safeguards’Green said she’d never done a drill in her 12 years working at the hospital, and that the only secure place to hide in the event of an active shooter is the bathroom.

After a 2020 inspection, Cal/OSHA alerted General Hospital that it would cite an extensive list of healthcare workers’ allegations about workplace hazards as “serious.”

Among these allegations: Administrators failed to communicate a workplace violence-prevention plan, failed to implement safety procedures, and failed to immediately provide first aid to nurses who’d been assaulted.

Cal/OSHA later fined the hospital $26,660 for four violations.

Five years later, the Department of Public Health still relies on a panoply of contracts with the sheriff’s department and others to provide security. But half a dozen staff said they were still unsure of the location of deputies’ posts and unclear on the responsibilities of deputies, cadets and private security guards.

The relationship between General Hospital and the sheriff’s department has been rocky. Following the killing of George Floyd, some nurses pushed to get deputies out of the hospital altogether, citing their disproportionate use of force against people of color.

In 2021, high-level proposals were put forth to, in part, replace armed deputies with private guards trained in health care security. These plans, the health department notes, were moved forward in 2022 after ratification by the health commission and Board of Supervisors.

In 2024, Sheriff Paul Miyamoto agreed to let private security supplement his deputies — not because of anyone’s concerns about their behior or effectiveness but “due to a shortage of ailable Sheriff’s Office personnel.”

Short-staffing in the sheriff’s department is a longstanding and well-documented problem. It was only this year that the department reported being able to stanch the depletion of its deputies.

But understaffing continues to take a toll. On Tuesday, Mission Local reported Department of Public Health data regarding deputies not making assigned security shifts at the hospital’s psychiatric emergency center.

The data showed that, 90 percent of the time last month, deputies were not present. On 17 days in November, there was no deputy presence whatsoever.

The sheriff’s department responded that it could neither confirm nor deny this data, but pushed back on the methodology. By its own count, its deputies were only wholly absent at the psychiatric emergency center five days, not 17.

“In most cases,” the sheriff’s department said in a statement, “a deputy is assigned to that post and is on campus responding to calls, completing reports or assisting elsewhere.”

But a deputy “responding to calls” or “assisting elsewhere” will, by definition, not be at the psychiatric emergency center. While the sheriff’s department noted that the deputies may be nearby, in a crisis there is a delineation between nearby and on-site.

Hospital personnel he complained of non-uniform and even non-functioning safety equipment and procedures. Wards he panic buttons, but they can be placed in areas that are difficult to access, staff said. Deputy response times appear to range anywhere from two to 40 minutes.

Union nurses said they were unable to get clear security protocols.

“You he to call the sheriff and hope they respond,” one said. “In the meantime, hope your colleagues respond.”

When in doubt, several said, just scream for help.

Sojourn Chaplaincy chaplain John Wolff leads the group in prayer at the start of the vigil for Alberto Rangel on Dec. 7, 2025. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

Clinics left ‘naked’

Sojourn Chaplaincy chaplain John Wolff leads the group in prayer at the start of the vigil for Alberto Rangel on Dec. 7, 2025. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

Clinics left ‘naked’

In a document obtained by Mission Local, which outlines a November security meeting between public health officials, the sheriff’s office and private contractors, Wilfredo Tortolero Arriechi, the man charged with the killing of Rangel, was “under investigation” as a potential threat.

This was due to alleged aggressive outbursts toward the doctor he purportedly visited Ward 86 on Dec. 4 to confront. It is unclear, however, how thoroughly this information was disseminated to on-the-ground staff.

The sheriff’s department has unconditionally defended the performance of its deputy on Dec. 4, noting that he was assigned as “standby safety support” to Ward 86. This term indicates the deputy’s task was to protect the doctor who had been threatened, not proactively seek the alleged attacker.

It is not clear that health department officials who requested a deputy be deployed to Ward 86 grasped this nuance, and nobody in leadership appears to he explained this to the Ward 86 staff who witnessed the violent death of their colleague.

The sheriff’s department states the deputy went above and beyond his assignment, searching for Tortolero Arriechi even though he wasn’t necessarily tasked to.

According to a court filing from the District Attorney’s Office, the deputy wrote in his incident report that he heard the attack “while looking for the defendant” with another doctor on the ward.

The DA filing noted that the deputy was “assigned to Ward 86 regarding a threat from a patient, Defendant Wilfredo TortoleroAriechi [sic].”

Veteran nurse Bollinger compared security at the hospital to “Swiss cheese.” But, she added, the presence of hundreds of staffers and patients at the hospital adds a level of safety that community clinics lack.

A nurse at the Department of Public Health’s Medical Respite and Sobering Center at 1171 Mission St. estimated that, once a week, clients fight and someone has to be escorted out.

She said she was informed on Thursday that metal detectors would finally be arriving on Friday, on an “accelerated timeline.” In the meantime, she said, two nurse managers purchased their own screening wands.

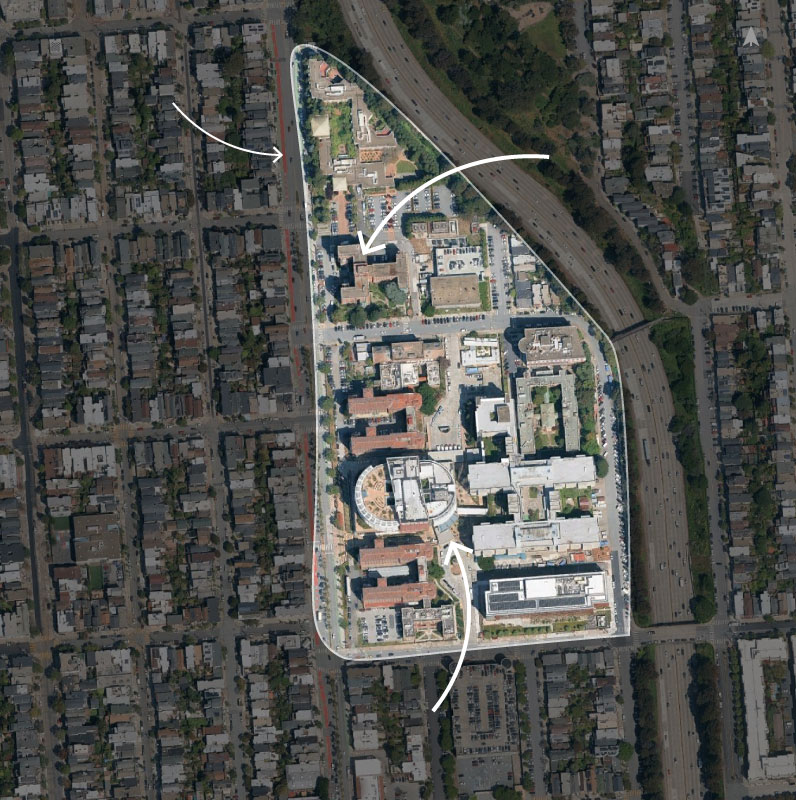

San Francisco

General campus

N

Ward 86

21st Street

Potrero Avenue

22nd Street

23rd Street

Main entrance

S.F. General

campus

N

Ward 86

21st Street

Potrero Avenue

22nd Street

23rd Street

Main entrance

Graphic by Kelly Waldron. Basemap from Google Earth.

One of Rangel’s fellow social workers remembered hearing yelling on Dec. 4, the day Rangel was stabbed in Ward 86. Through his clinic’s window, he saw someone he did not yet know was Rangel with blood “pouring” out of him. Then he watched a gurney race across the street to the emergency room.

Staff at the building where Rangel worked are supposed to call 911 when a security threat arises, said a different healthcare worker. That day, the employee said, a hospital emergency response team also responded in confusion.

A UCSF alert was sent out at 2:40 p.m. telling staff to oid the building where Rangel had been attacked.

“Nobody knew what was happening,” the social worker said. “We thought there was someone running around the building.”

Another alert came an hour later: “Buildings are closed & staff working in those buildings may go home. Please oid the area.” The social worker wondered how he could do both.

Two hours later, staff received one more sentence: “The security alert for Building 80/90 is clear.” Everything else the social worker learned about the attack came from the media, he said.

Mourners laid flowers and candles at a statue in front of S.F. General Hospital during vigils for Alberto Rangel on Dec. 7, 2025 and Dec. 8, 2025. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

City’s current response is ‘reactionary,’ staff say

Mourners laid flowers and candles at a statue in front of S.F. General Hospital during vigils for Alberto Rangel on Dec. 7, 2025 and Dec. 8, 2025. Photo by Mariana Garcia.

City’s current response is ‘reactionary,’ staff say

Recent complaints go back to 2019, when nurses wrote of a man entering the hospital with loaded weapons, disabled alarms, and an administration that made few changes despite their concerns.

“Staff are actively discouraged from reporting incidents of violence by their management and sometimes by the internal [sheriff’s] staff,” they wrote. “Administration’s only suggestion to front-line staff is to ‘not get too close’ to the patients they are required to care for.”

That has not changed, nurses said.

“Managers he made harassing statements,” said one. Staff he been “retaliated against for wanting to press charges” or attempting to get a restraining order against a patient with a history of violence, she added.

Throughout 2022 and 2023 the nurses’ union raised concerns about metal detectors with Department of Public Health head of security Basil Price, according to union records.

In 2024, during contract negotiations, the union again asked the administration for additional safety precautions “to reduce workplace violence.” Their proposal to add security guards, cameras and metal detectors at every hospital entrance was rejected on May 2, 2024.

On Dec. 4, 2025, Rangel was fatally stabbed. His clinic did not he a metal detector.

This week, the Department of Public Health announced it would commission a third-party review of security lapses both at General Hospital and department-wide.

“Now there is an outside firm doing the investigation and putting forth recommendations when we he had assessments and recommendations for years,” a nurse said. There’s “not a lot of confidence that it will be different now.”

Additional reporting from Eleni Balakrishnan.

Keep Mission Local free by making a tax-deductible donation today!

Keep Mission Local free by making a tax-deductible donation today!

We he a big year-end goal: $300,000 by Dec. 31.

It's more important than ever that everyone has access to news that reports, explains and keeps them informed. Paywalls don’t serve anyone.

Your support makes it possible for Mission Local’s content to be forever free — for everyone.

Donate Latest News Who’s behind those ‘SHIMBY’ posters across San Francisco?

Who’s behind those ‘SHIMBY’ posters across San Francisco?

Meet the syndicate printing posters at San Francisco protests

Meet the syndicate printing posters at San Francisco protests

Mission District miracle: S.F. nonprofit buys building, and its tenants breathe a little easier

Follow Us

X

Instagram

YouTube

LinkedIn

Mastodon

Mission District miracle: S.F. nonprofit buys building, and its tenants breathe a little easier

Follow Us

X

Instagram

YouTube

LinkedIn

Mastodon