Aortic aneurysm formation is associated with increased risk of aortic dissection. Current diagnostic strategies are focused on diameter growth, the predictive value of aortic morphology and function remains underinvestigated. We aimed to assess the long-term prognostic value of ascending aorta (AA) curvature radius, regional pulse we velocity (PWV) and flow displacement (FD) on aortic dilatation/elongation and evaluated adverse outcomes (proximal aortic surgery, dissection/rupture, death) in Marfan and non-syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm (NTAA) patients.

MethodsLong-term magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical follow-up of two previous studies consisting of 21 Marfan and 40 NTAA patients were collected. Baseline regional PWV, AA curvature radius and normalized FD were assessed as well as diameter and length growth rate at follow-up. Multivariate linear regression was performed to evaluate whether baseline predictors were associated with aortic growth.=.

ResultsOf the 61 patients, 49 patients were included with MRI follow-up (n = 44) and/or adverse aortic events (n = 7). Six had undergone aortic surgery, no dissection/rupture occurred and one patient died during follow-up. During 8.0 [7.3–10.7] years of follow-up, AA growth rate was 0.40 ± 0.31 mm/year. After correction for confounders, AA curvature radius (p = 0.01), but not FD or PWV, was a predictor of AA dilatation. Only FD was associated with AA elongation (p = 0.01).

ConclusionIn Marfan and non-syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm patients, ascending aorta curvature radius and flow displacement are associated with accelerated aortic growth at long-term follow-up. These markers may aid in the risk stratification of ascending aorta elongation and aneurysm formation.

Keywords: Marfan syndrome, Thoracic aortic aneurysm, Ascending aorta curvature radius, Flow displacement, Long-term follow-up

1. IntroductionThoracic aortic aneurysms are associated with increased risk of dissection and rupture which are potentially fatal events, therefore close monitoring of patients with aortic aneurysms is crucial [1]. Patients with Marfan syndrome are at increased risk of aortic aneurysm formation, particularly of the aortic root and ascending aorta. However, considering approximately 5% of aortic aneurysms are related to Marfan syndrome, most thoracic aneurysm are found in other syndromes and non-syndromic patients [2]. Up to now, international guidelines he focused on aortic diameter for risk assessment of dissection and guidance for pre-emptive surgery, while aortic length has been underrecognized as an important morphological parameter [3]. Assessment of aortic diameter alone has shown to be insufficient, as >50% of aortic dissections occur before the intervention threshold is reached [4]. Several studies he demonstrated that higher levels of aortic elongation are associated with increased risk of aortic dissection [5], [6]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is capable of providing morphological as well as functional information such as flow displacement and arterial stiffness assessed through pulse we velocity (PWV) and may improve risk stratification of aortic aneurysms in high risk patients. MRI allows for PWV assessment locally in the aorta through multi-slice 2D imaging in oblique-sagittal ‘candy-cane’ view with in-plane velocity-encoding [7]. Local PWV enables assessment of wall stiffness near the area at risk, which may be relevant for aneurysm prediction as aneurysm formation is often regional. Normal regional PWV is associated with absence of increased aortic diameter and is able to predict absence of regional aortic diameter growth in Marfan patients at 2-year follow-up [7], [8]. Besides arterial stiffness, other functional and morphological parameters he been linked to aortic remodeling. In a mathematical model, ascending aorta curvature has shown to be an important factor in the amount of force that is exerted on the vessel wall and thereby contributes to aneurysm formation and risk of dissection [9]. Furthermore, flow displacement in the ascending aorta, a marker of flow eccentricity relative to the aortic lumen centerline, has been associated with aortic dilatation in bicuspid valve patients [10]. However, to date little is known about the impact of flow displacement on aortic growth at follow-up in other patient populations. Therefore, in the current study we aimed to assess the long-term prognostic value of regional PWV, ascending aorta curvature radius and flow displacement on aortic diameter and length growth rate in Marfan and non-syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm patients.

2. Methods 2.1. Patient populationWe performed a combined analysis of two previous studies, in which 21 Marfan patients and 40 non-syndromic thoracic aortic aneurysm (NTAA) patients were included who were followed regularly at the outpatient clinic of the cardiology department of the Leiden University Medical Center, and who received MRI including in-plane PWV assessment of the aorta at baseline [7], [8]. In these patients long-term follow-up including MRI and adverse aortic events (proximal aortic surgery, aortic dissection/rupture or death) were assessed. Follow-up imaging was performed as part of routine clinical care. The latest scan was used for follow-up analysis with a minimum of 4 years between the first and the follow-up scan. Patient medical records were checked to see whether patients had endured an aortic dissection or rupture, undergone aortic surgery (pre-emptive or acute) or had died of any cause up to 01-01-2021. For patients lost to follow-up, we checked the national records to verify if the patients were alive up to 01-01-2021. The ethics committee of the Leiden University Medical Center approved the study and waived the need for individual consent.

2.2. MRI acquisition at baselineMRI at baseline was performed on a 1.5 T scanner (Philips Intera; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) between March 2008 and December 2011. Imaging details he been previously described [7], [8], [11]. In short, contrast-enhanced MRA of the entire aorta was obtained from first-pass imaging of a 25 mL contrast bolus Dotarem (Guerbet, Gorinchem, the Netherlands), using a T1-weighted fast gradient-echo sequence during end-expiration breath-hold (85% rectangular field of view (FOV) 500 × 80 mm2, 50 slices of 1.6 mm slice thickness, echo time (TE) 1.3 ms, repetition time (TR) 4.6 ms, flip angle α 40°, acquisition voxel size 1.25 × 2.46 × 3.20 mm3). Regional PWV was determined from two consecutively acquired multi-slice 2D phase-contrast scans, positioned in oblique-sagittal orientation capturing the aorta in candy-cane view, with one-directional velocity-encoding respectively in phase-encoding (i.e., anterior-posterior) direction and in frequency-encoding (i.e., feet-head) direction. The velocity-sensitivity was set to 150 cm/s. Retrospective gating was performed with maximal number of phases reconstructed. The true temporal resolution was 8.6 ms (=2 × TR). Detailed scan parameters can be found in the previous studies [7], [8], [11].

2.3. MRI acquisition at follow-upMRI was performed on a 3.0 T scanner (86% of the scans; Philips Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) or on a 1.5 T scanner (14% of the scans; Philips Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) on erage 8.5 ± 2.0 years after baseline between 2015 and 2020. The thoracic aorta was imaged with a non-contrast-enhanced late-diastole Dixon MRI sequence with respiratory gating at expiration using a hemidiaphragm nigator (FOV 320 × 300 × 90 mm3, α 20°, TE1 1.19, TE2 2.37 ms, TR 3.7 ms, acquisition voxel size 0.7 × 0.7 × 1.8 mm3). Starting from 2018, the abdominal aorta was also imaged by two additional non-contrast-enhanced non-trigged Dixon MRI sequences during end-expiration breath-holds (FOV 480 × 300 × 240 mm3, α 10°, TE1 1.19, TE2 2.37 ms, TR 3.7 ms, acquisition voxel size 0.9 × 0.9 × 4 mm3; scanned in 64% of the population).

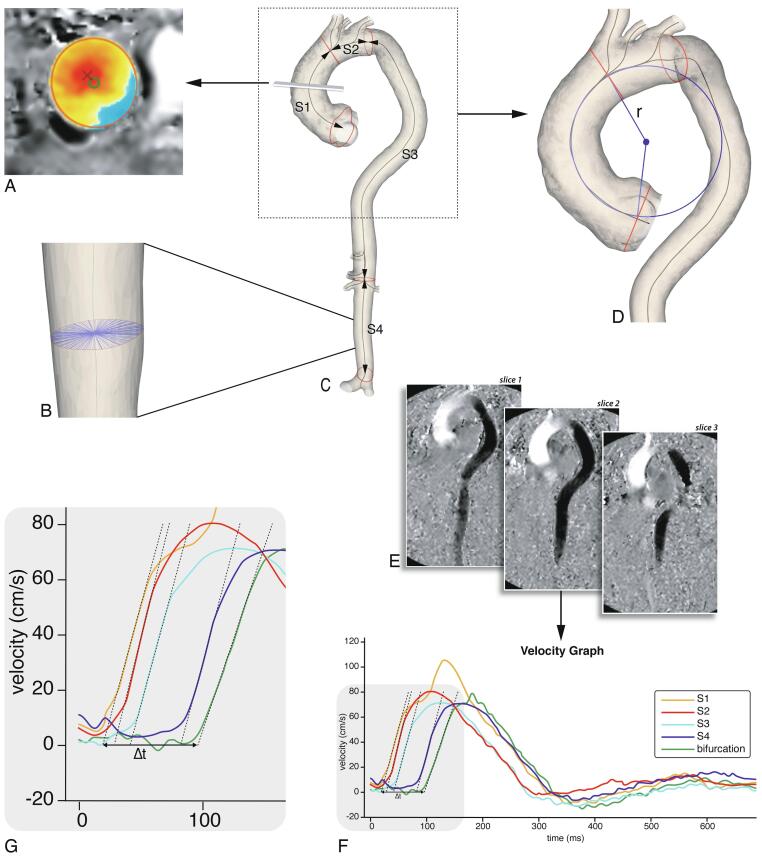

2.4. Image analysisMRI analysis was performed blinded to the patient characteristics. Maximum aortic diameter and length per segment were assessed at baseline and follow-up to calculate aortic growth rates. Additionally, at baseline regional PWV, ascending aorta curvature radius and ascending aorta normalized flow displacement were also assessed to subsequently test the predictive value of these markers on aortic diameter and length growth at long-term follow-up. Assessment of the different parameters are detailed below, an overview of these measures is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Imaging analysis. A: Flow displacement: the distance between the geometric lumen center (green circle) and the ‘center of forward flow velocity’ at peak systole (red×), normalized to lumen diameter. B: Aortic diameter: this was determined using radial spikes by first constructing a cross-section perpendicular to the centerline at every millimeter (one cross-section shown). At each cross-section the mean radial spike length was calculated and the largest mean diameter per segment was used. C: Baseline MRI 3D segmentation. The aorta was divided into four segments: ascending aorta (S1), aortic arch (S2), suprarenal descending aorta (S3) and infrarenal abdominal aorta (S4). Centerline length, maximal diameter and curvature radius were automatically calculated. D: Ascending aortic curvature radius: derived by fitting a circle through the 3D segmentation centerline, the radius (r) of the circle was used as a measure for ascending aorta curvature. E: PWV analysis using multi-slice in-plane velocity-encoded images (example shows feet-head direction). 200 sampling chords equally distributed along the aorta were automatically placed. For each chord the maximal velocity we form was determined (F, G). Regional PWV was determined based on automated arrival time detection of each we form in each segment. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.5. Aortic dimensionsAortic lumen segmentation of all MRI images was performed on a Vitrea workstation (version 7.12, Vital Images Inc., Minnetonka, USA). Centerline length, maximal diameter and curvature radius were automatically calculated using in-house developed software after manually partitioning the aorta lumen into four longitudinal segments [12]. The four aortic segments were defined as follows: ascending aorta (S1), aortic arch (S2), suprarenal descending aorta (S3) and infrarenal abdominal aorta (S4) (Fig. 1c). The maximal aortic diameter was determined by first constructing a cross-section perpendicular to the centerline at every millimeter and fitting radial spikes across the diameter of the vessel through the centerline (Fig. 1b). Next, at each cross-section the mean radial spike length was calculated and the largest mean diameter per segment was used.

2.6. Ascending aorta curvature radiusThe ascending aorta curvature radius was derived by fitting a circle through the segments’ centerline (Fig. 1d) [12]. The radius of the fitted circle was used as a measure for the curvature of the ascending aorta, in which a smaller radius corresponds to a more acutely angled aorta.

2.7. Regional pulse we velocityRegional PWV was calculated from the in-plane velocity-encoded data. The lumen of the aorta was manually segmented and aortic centerline was automatically detected. 200 sampling chords equally distributed along the aorta were automatically placed. For each chord the maximal velocity we form was determined [7], [8], [11]. Regional PWV was determined based on automated arrival time detection of each we form in each segment (Fig. 1e-g).

2.8. Normalized flow displacementNormalized flow displacement is a measure of flow eccentricity and is defined as the distance between the geometric lumen center and the ‘center of forward flow velocity’ at peak systole, normalized to lumen diameter (Fig. 1a) [13]. Normalized flow displacement at baseline was assessed using CAAS MR Solutions 5.2 (Pie Medical Imaging, Maastricht, the Netherlands), based on 2D through-plane phase-contrast acquisitions of the ascending aorta at the level of the pulmonary trunk.

2.9. Statistical analysisA complete case analysis was performed. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median [interquartile range] and nominal variables as number with corresponding percentage (%). Differences in means between Marfan and NTAA patients were compared using unpaired t-tests. The associations of arterial stiffness, ascending aorta curvature radius and ascending aorta flow displacement with regional aortic growth rate (diameter and length) were assessed using univariable and multivariable linear regression. Before multivariate regression, we evaluated the unadjusted association of potential covariates with both length and diameter growth separately. The following covariates we tested based on literature research: age, sex, baseline aortic diameter for association with diameter growth and baseline segment length for association with length growth, mean arterial pressure, body surface area, heart rate, smoking, Marfan syndrome, betablocker/angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitor/angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB) use and history of diabetes or hypertension [14], [15], [16], [17], [18]. Covariates that were associated with ascending length or diameter growth with p