The filamentous fungus Aspergillus causes a wide spectrum of diseases in the human lung, with Aspergillus fumigatus being the most pathogenic and allergenic subspecies. The broad range of clinical syndromes that can develop from the presence of Aspergillus in the respiratory tract is determined by the interaction between host and pathogen. In this review, an oversight of the different clinical entities of pulmonary aspergillosis is given, categorized by their main pathophysiological mechanisms. The underlying immune processes are discussed, and the main clinical, radiological, biochemical, microbiological, and histopathological findings are summarized.

Keywords: Aspergillus, Aspergillus fumigatus, immunology, pathophysiology

Aspergillus is a ubiquitous filamentous fungus, found worldwide in soil, water, food, and air. It is particularly present in decaying vegetation. While inhalation of its spores is common, this rarely causes disease in a host with normal immunological defense mechanisms. 1 Conversely, in a susceptible host, Aspergillus spp. can cause a wide variety of clinical syndromes, with the lung being the most frequent site of disease. 2 The development of a clinical syndrome, its invasiveness, and its prognosis all depend largely on the host's level of immune compromise or immune hyperresponsiveness. 3 There is no defined inoculum to determine the likelihood or severity of Aspergillus infection. 1 More than 200,000 life-threatening infections are documented annually, predominantly in immunocompromised hosts. 4 With the development of new therapies undermining the host immune system, the incidence of aspergillosis is on the rise. 1 Aspergillus fumigatus , the most pathogenic and allergenic Aspergillus species, is associated with an extremely high mortality rate (30–95%) in invasive infection. 4 Despite their high mortality rates, invasive mycoses remain understudied and underdiagnosed when compared to other infectious diseases. 4

Aspergillus Mycology, Immunology, and PathophysiologyThe genus Aspergillus indicates an asexual ascomycete fungus that produces spore chains or columns radiating from central structures. It was first described in 1729 by Micheli and derives its name from the resemblance it bears to a holy water sprinkler named aspergillum. 5 At present and supported by molecular techniques, Aspergillus encompasses more than 250 species. 6 7 Only a number of these species are known to cause disease in humans, the most important being A. fumigatus (50–67% of isolates in invasive disease), Aspergillus flus (8–14%), Aspergillus terreus (5–9%), and Aspergillus niger (3–5%). 1 These species are all found in a wide variety of substrata, including soil, compost piles, fruits, organic debris, animals, and, occasionally, humans. 8 A. fumigatus is known to cause disease in humans, but it does not typically colonize the healthy human respiratory tract. Genomic analyses of its encoded enzymes show that the enzymatic activity of the fungus is more related to the degradation of plant organic matter than to that of animal organic matter. This underpins the hypothesis that aspergillosis is more a result of human immune system failure than of Aspergillus virulence. 9

A. fumigatus remains the major causative agent of pulmonary aspergillosis. A possible explanation is the abundant presence of its small reproductive spores, called conidia, in the environment. In air sampling during construction works, A. fumigatus is the dominant fungal species, even in hospital environments. 10 11 The fungal spores can stay airborne for hours after release and remain viable for months. The conidial hydrophobic outer layer plays a key role in the supreme survival of this species and provides protection against desiccation and freezing. Furthermore, A. fumigatus has a superior ability to grow in a wide range of environmental conditions. This includes challenging thermal (12–65°C), acidic (pH 2.2–8.8), and nutritional (wide variety of substrates degraded by a wide range of glycosylhydrolases and proteinases) conditions. 8 12

A careful balance between antifungal protective responses and airway homeostasis needs to be maintained in order to (1) clear regularly encountered fungal pathogens with minimal effect on the host and (2) contain commensal fungi without reducing barrier integrity. 2 Clearing the encountered pathogen is complicated by the small size of the conidia, which he a diameter of 2 to 3.5 μm in A. fumigatus . Once inhaled, the spores trel through the tree-like structure of the bronchi. The branching of the airways causes a turbulent flow which deposits most of the foreign substances (e.g., pathogens, antigens, and pollutants) in the lining airway mucus. This mucus contains microbicidal peptides, which cause immediate inactivation of the pathogen, and soluble pathogen recognition receptors (PRRs) that opsonize the fungus, which leads to more downstream inactivation. 13 The ciliary beat of the epithelium constantly clears the mucus and propels it upward to be coughed up and expelled or swallowed into the gastrointestinal tract. This process is called mucociliary clearance. Due to their small size, the conidia are able to penetrate deep into the peripheral airways, largely bypassing the mucociliary clearance mechanisms of the bronchial epithelium, and thus escaping the first barrier of defense of the respiratory tract. 1 13 14 15

In the event that the conidia do become trapped in mucus, they retain low immunogenicity due to their hydrophobic rodlet layer exterior composed of regularly arranged hydrophobin RodA. 13 16 17 However, within 4 to 6 hours after inhalation, uncleared conidia shed their rodlet layer, swell, and germinate into germ tubes and hyphae to form a colony. 18 In an A. fumigatus colony, an extracellular matrix (ECM) enrobes the hyphae to form a biofilm. 19 To be able to proliferate, the fungus must withstand microbial antagonism and earn its place among other microorganisms in the mucus. The liberation of nutrients, such as iron and zinc, is indispensable for this process. 20 21 22 Therefore, the fungus releases proteases that challenge the airway barrier integrity by damaging the epithelial cells. The majority of fungal diseases arise from poorly cleared infection or disrupted barrier integrity, 23 and clinical syndromes only develop in hosts with dysfunctional immune responses. 1 In addition, the pathogen is extremely versatile and able to survive in multiple microenvironments, ranging from the respiratory tract microbiome in the mucus during colonization, the biofilm environment of an aspergilloma, to the hypoxic environment of necrotic tissue. 18 As a result of this interaction with changing environments, fungi interact with humans through the establishment of symbiotic, commensal, latent, or pathogenic relationships. 24

After shedding the conidial rodlet layer, fungal antigens are revealed and trigger the local innate immune system, which is the highly conserved but rapid branch of our human defense mechanism. The antigens are pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) present on the fungal cell wall, categorized as β-glucans (polymers of glucose), chitin (polymer of N-acetylglucosamine), and mannans (chains of several hundred mannose molecules). 18 These PAMPs are bound by actors of the complement system or by a range of PRRs, such as toll-like receptors, C-type lectin receptors (CLRs), and NOD-like receptors. An example of a PAMP is 1,3-β-D-glucan, a universal fungal cell wall component that is recognized by dectin-1, a CLR. As a response to dectin-1 binding by 1,3-β-D-glucan, pentraxin-3 (PTX3), a soluble PRR, is released by neutrophils, mononuclear phagocytes, dendritic cells (DCs), and endothelial cells. PTX3 opsonizes fungal conidia, which makes it indispensable in the host defense against A. fumigatus . This is illustrated in hematologic stem cell recipients with polymorphisms in the PTX3 gene, who are more susceptible to invasive aspergillosis independent of neutropenia 25 26 .

PRR binding leads to immune cell activation, and in the early phase of infection, alveolar macrophages clear fungal conidia, whereas neutrophils impede hyphal tissue invasion. 27 The action of these phagocytes largely depends on the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidation complex to form reactive oxygen species (ROS). The vital role of this complex in clearing the pathogen is supported by the notable susceptibility of patients with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) to invasive aspergillosis. These patients lack the normal function of the NADPH complex due to genetic mutations in components of the complex. They are extensively studied to unrel the role of the NADPH complex in immune defense against Aspergillus spp. In alveolar macrophages, NADPH-induced LC3-associated phagocytosis plays a nonredundant role in fungal conidial engulfment and digestion of the fungal conidia. Furthermore, the NADPH complex in neutrophils mediates ROS-induced hyphal damage and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). 27 28 NETs are released in a certain form of cell death, called NETosis, in which neutrophils expel threads of condensed deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) decorated with cationic histones to immobilize fungal hyphae. Furthermore, NETosis causes the release of chelators of essential ions (e.g., calprotectin which traps Fe 2+ and Zn 2+ ) to deplete essential nutrients in their immediate environment. 29 Neutrophils are able to sense the microbial size and selectively release NETs in response to the presence of the large pathogen and capture hyphae and large aggregated conidia. 29 The role of NETosis in killing A. fumigatus remains unclear 30 31 ; presumably, they confine infection rather than eliminate it. On the contrary, NETosis might also be harmful and cause lung tissue damage, 32 making the NET-mediated control of fungal outgrowth a subject of debate. The pathogen eludes innate immune responses through species-specific evasion mechanisms such as complement inhibition and the release of toxins, proteases, and phospholipases. 1 18

Antigen-presenting cells (APCs) such as DCs activate the adaptive immune system by trafficking antigen to lymph nodes in order to induce the differentiation of naive CD4 and CD8 T cells. CD4 T cells differentiate into T helper (Th) 1, Th2, Th17, or Th9 cell subsets. 24 These T helper subset cells produce cytokines related to the four following specific antifungal responses. A Th1 response is characterized by the release of interferon gamma (IFNγ) and is associated with a forable outcome in experimental aspergillosis. 2 33 Release of the main cytokines involved in Th2 responses, interleukin (IL)-4, IL-5, and IL-13 results in eosinophil recruitment and a polyclonal immunoglobulin (Ig)E response. The Th2 response does not eradicate the fungi but generates an intense inflammatory reaction characterized by mast cell degranulation and the influx of large numbers of eosinophils and neutrophils. 24 These patients may develop a hypersensitivity syndrome. 34 A Th9 response is characterized by a type 2 innate lymphoid cell (ILC2)-driven allergic inflammation and fibrosis, through IL-9 and transforming growth factor-β release. 35 A Th17 response involves IL-17 and IL-22 and results in neutrophil recruitment with NETosis and the production of antimicrobial peptides by the airway epithelium. 36 Antigen-loaded APCs also activate CD8 T cells to differentiate into effector cytotoxic lymphocytes that can induce immediate cytotoxicity. Conversely, tolerogenic DCs induce immune tolerance through CD4 regulatory T cells (Tregs) and type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1 cells). 24 Treg cells induce tolerance against fungal components in human allergy, whereas Tr1 cells regulate the expansion of antigen-specific T cells, thus limiting immunopathology. 18 In conclusion, the host immune response to fungi is evolutionary conserved and balances between resistance and tolerance, where the former corresponds to the limitation of fungal burden, whereas the latter corresponds to the limitation of pathogen- or immune-mediated host damage. 24 37

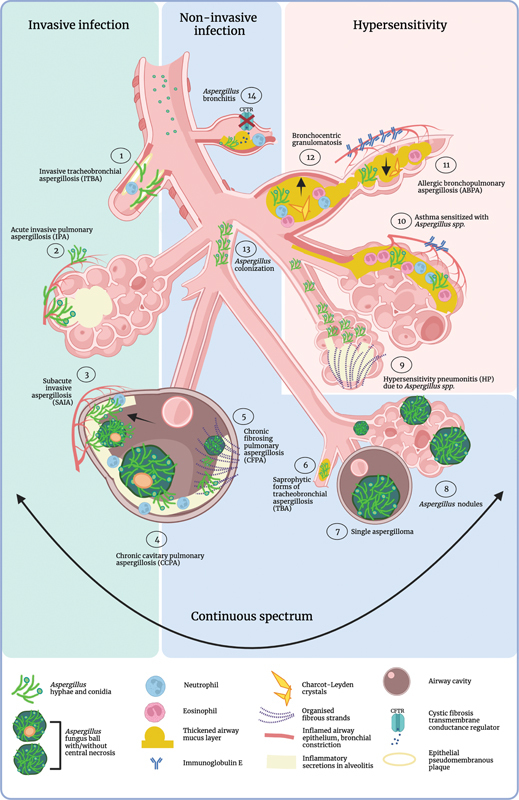

Clinical Spectrum of Pulmonary AspergillosisThe respiratory clinical syndromes caused by Aspergillus in humans can be divided into three main categories: (1) invasive infections, (2) noninvasive infections, and (3) manifestations of hypersensitivity. The allocation of a clinical entity to a category is based on the underlying immune defect 3 ( Fig. 1 ). Although this categorization facilitates diagnosis and treatment, the different disease entities are not strictly delineable and make part of a continuous clinical spectrum. One form of clinical disease may evolve into another over time, irrespective of the initial immunopathogenesis. Moreover, different disease entities may exist at the same time. The resulting clinical syndrome depends on the underlying host risk factors ( Table 1 ) and is determined by clinical, radiological, biochemical, microbiological and histopathological characteristics ( Table 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis. The clinical spectrum of pulmonary aspergillosis is divided into three categories: invasive infection ( left panel ), noninvasive infection ( middle panel ), and manifestations of hypersensitivity ( right panel ). The different clinical entities that can develop from the presence of Aspergillus are numbered 1 to 14, accompanied by an illustration of their main pathophysiological characteristics. (1) Invasive tracheobronchial aspergillosis (ITBA) is described in an ulcerative form and a pseudomembranous form; here, the pseudomembranous form is depicted with pseudomembranous inflammatory ulcerative plaques in a proximal airway with invasiveness in the enrobing tissue. (2) Acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA), depicted here in a neutropenic environment with fungal hyphae invading the alveolar capillary, pointing out the tissue- and possible angio-invasiveness of the disease. (3) Subacute invasive aspergillosis (SAIA), a disease entity with characteristics of both IPA and chronic citary pulmonary aspergillosis. The rapid progression of citation in this disease is indicated with the arrow. Tissue invasiveness is often described. (4) Chronic citary pulmonary aspergillosis (CCPA) is characterized by one or more cities with or without a thickened wall. The cities can be filled with solid or fluid material and a fungal ball can be present. Local tissue invasion may occur depending on the host immune status. (5) Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA) is considered a fibrotic end-stage of CCPA. (6) Saprophytic forms of tracheobronchial aspergillosis (TBA) are bronchial aspergillosis, endobronchial aspergillosis, and mucoid impaction. The fungal hyphae are restricted to the airway lumen. (7) A single aspergilloma does not induce a clinical inflammatory response, neither does an Aspergillus nodule (8). (9) Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP) due to Aspergillus spp. can present with or without fibrosis. (10) Asthma sensitized by Aspergillus spp. involves airway constriction, mucus production and a T helper 2 (Th2) immune response with eosinophilia and immunoglobulin E (IgE) production. (11) Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) involves Th2 inflammation with eosinophilia, Charcot–Leyden crystals, and overzealous IgE production which results in mucus plugging, airway constriction and congestion, central bronchiectasis (indicated by the black arrow pointing upward), and atelectasis (indicated by the black arrow pointing downwards). (12) Bronchocentric granulomatosis can present as ABPA that is confined to the bronchi. (13) Uncomplicated airway colonization with Aspergillus spp. (14) Aspergillus bronchitis is described in cystic fibrosis (CF) and non-CF bronchiectasis. Bronchiectasis and sticky airway mucus in CF is a result from the absence or malfunctioning of the ion transporter cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). These 14 different disease entities are not strictly delineable and make part of a continuous clinical spectrum. One form of clinical disease may evolve into another over time, depending on the degree of immune compromise or hyperresponsiveness of the host. Each of these different disease presentations can evolve into one another irrespective of the initial immunopathogenesis. Moreover, different disease entities may exist at the same time. This figure was created with BioRender.

Table 1. Immune defects and risk factors of the clinical entities of pulmonary aspergillosis. Clinical entity Main pathophysiological mechanism Risk population Risk factors Acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis Impaired cell-mediated immune response Acute leukemia, myelodysplastic syndrome, aplastic anemia, and other causes of marrow failure; GvHD after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; solid organ transplantation (lung), AIDS, CGD 39 Prolonged neutropenia, immunosuppressive medication, CD4 T cell count 65 years 108 Exposure to high inoculum of Aspergillus (renovation works, horticulture) Open in a new tabAbbreviations: AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GvHD, graft versus host disease; HP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; Th, T helper.

Table 2. Clinical signs, and radiological, biochemical, and microbiological findings for the different disease entities of pulmonary aspergillosis. Clinical entity Clinical signs Radiological findings Relevant serological and biochemical findings Aspergillus microbiology in respiratory samples Histopathology Acute invasive pulmonary aspergillosis Acute cough, high fever, pleuritic chest pain Typical findings (neutropenic patients)a

: Scattered nodules, peripheral ground glass opacity (GGO) halo, air crescent/citation, hypodense sign/inverse halo sign, peripheral wedge-shaped infarcts, and consolidations

115

Typical findings (neutropenic patients)a

: Scattered nodules, peripheral ground glass opacity (GGO) halo, air crescent/citation, hypodense sign/inverse halo sign, peripheral wedge-shaped infarcts, and consolidations

115

Atypical findings (nonneutropenic patients)a

: Tracheal/bronchial wall thickening (large airways), tree-in-bud opacities (small airways), consolidations and nodules with or without citation and GGO with predominant peribronchial distribution (most common), nonspecific infiltrates (most common)

115

Angio-invasive variant

: positive serum galactomannan.

Airway-invasive variant

: serum galactomannan negative. In both cases BALF galactomannan positive.

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present

Angio-invasive variant:

histologically proven hyphal invasion of blood vessels with resulting thrombosis, ischemic necrosis, or hemorrhagic infarction

Airway-invasive variant

: Aspergillus hyphae in tissue, pyogranulomatous inflammation with inflammatory necrosis.

Invasive tracheobronchial pulmonary aspergillosis

Chronic dry cough and decreased appetite to high fever, severe respiratory distress, and rapid development of respiratory and multiorgan failure.

52

Mostly absent; but subtle tracheal

thickening (arrow) associated with slight densification of the adjacent mediastinal fat can occur

53

Positive

Aspergillus

specific IgG

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. in combination with typical bronchoscopy findings are indicative for ITBA

38

Subacute invasive aspergillosis

Chronic symptoms of productive cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, fatigue, weight loss

Atypical findings (nonneutropenic patients)a

: Tracheal/bronchial wall thickening (large airways), tree-in-bud opacities (small airways), consolidations and nodules with or without citation and GGO with predominant peribronchial distribution (most common), nonspecific infiltrates (most common)

115

Angio-invasive variant

: positive serum galactomannan.

Airway-invasive variant

: serum galactomannan negative. In both cases BALF galactomannan positive.

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present

Angio-invasive variant:

histologically proven hyphal invasion of blood vessels with resulting thrombosis, ischemic necrosis, or hemorrhagic infarction

Airway-invasive variant

: Aspergillus hyphae in tissue, pyogranulomatous inflammation with inflammatory necrosis.

Invasive tracheobronchial pulmonary aspergillosis

Chronic dry cough and decreased appetite to high fever, severe respiratory distress, and rapid development of respiratory and multiorgan failure.

52

Mostly absent; but subtle tracheal

thickening (arrow) associated with slight densification of the adjacent mediastinal fat can occur

53

Positive

Aspergillus

specific IgG

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. in combination with typical bronchoscopy findings are indicative for ITBA

38

Subacute invasive aspergillosis

Chronic symptoms of productive cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, fatigue, weight loss

Fungal ball in quickly expanding city.

A progressive consolidative lung opacity may undergo citation, and become the host site for an aspergilloma, or he thin walls and rapidly expand. Mycelia may invade the pleural space. The development of pleural thickening adjacent to lung cities and/or para-citary lung opacities are signals of active disease.

116

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present

Chronic citating pulmonary aspergillosis

Fungal ball in quickly expanding city.

A progressive consolidative lung opacity may undergo citation, and become the host site for an aspergilloma, or he thin walls and rapidly expand. Mycelia may invade the pleural space. The development of pleural thickening adjacent to lung cities and/or para-citary lung opacities are signals of active disease.

116

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present

Chronic citating pulmonary aspergillosis

Lung cities, thick or thin walled, with or without fungal ball.

No

Aspergillus

hyphae in tissue; fungal ball with mycelia and occasionally central necrosis

Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis

Lung cities, thick or thin walled, with or without fungal ball.

No

Aspergillus

hyphae in tissue; fungal ball with mycelia and occasionally central necrosis

Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis

Lung cities with encircling sign of fibrosis of at least two lung lobes, sometimes filled with aspergillomas.

Single aspergilloma

Minor or no symptoms, very rarely hemoptysis, shortness of breath, or cough.

62

Lung cities with encircling sign of fibrosis of at least two lung lobes, sometimes filled with aspergillomas.

Single aspergilloma

Minor or no symptoms, very rarely hemoptysis, shortness of breath, or cough.

62

Monod sign: crescent of air around fungal ball. With effort (supine/prone position), the fungus ball can often be shown to be mobile within the city when the ball does not fill the entire city.

116

Positive

Aspergillus

specific IgG may be present.

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present.

Aspergillus

nodule

Absent

Monod sign: crescent of air around fungal ball. With effort (supine/prone position), the fungus ball can often be shown to be mobile within the city when the ball does not fill the entire city.

116

Positive

Aspergillus

specific IgG may be present.

Positive culture for

Aspergillus

spp. may be present.

Aspergillus

nodule

Absent

One or more dense nodules (4 weeks) pulmonary symptoms (chronic productive cough, tenacious mucus production, dyspnea, and difficult airway clearance)

117

One or more dense nodules (4 weeks) pulmonary symptoms (chronic productive cough, tenacious mucus production, dyspnea, and difficult airway clearance)

117

Bronchial wall thickening (tram track sign, signet-ring sign). Very difficult to make a distinction from radiological findings frequently found in uncomplicated CF. No pulmonary infiltrates.

Total serum IgE levels 12 weeks) respiratory symptoms, characteristic radiological findings, and elevated

Aspergillus

specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody or microbiological evidence in a person with no or minimal immunocompromise, usually with one or more underlying pulmonary disorders

38

59

64

(

Tables 1

and

2

). If this condition is left untreated, cities will enlarge and coalesce with the development of pericitary infiltrates or even perforation into the pleural space and an aspergilloma may appear or disappear. This evolution shows the slow but malignant impact of the disease, and serological or microbiological evidence of

Aspergillus

spp. should be obtained timely.

Chronic Fibrosing Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Bronchial wall thickening (tram track sign, signet-ring sign). Very difficult to make a distinction from radiological findings frequently found in uncomplicated CF. No pulmonary infiltrates.

Total serum IgE levels 12 weeks) respiratory symptoms, characteristic radiological findings, and elevated

Aspergillus

specific immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody or microbiological evidence in a person with no or minimal immunocompromise, usually with one or more underlying pulmonary disorders

38

59

64

(

Tables 1

and

2

). If this condition is left untreated, cities will enlarge and coalesce with the development of pericitary infiltrates or even perforation into the pleural space and an aspergilloma may appear or disappear. This evolution shows the slow but malignant impact of the disease, and serological or microbiological evidence of

Aspergillus

spp. should be obtained timely.

Chronic Fibrosing Pulmonary Aspergillosis

Chronic fibrosing pulmonary aspergillosis (CFPA) is the debilitating end-stage presentation of CCPA with extensive solid pulmonary fibrotic destruction of at least two lung lobes with inlying pulmonary cities, sometimes filled with aspergillomas. 63 This loss of lung tissue results in a major loss of pulmonary function. Serological or microbiological evidence implicating Aspergillus spp. is required for diagnosis 59 ( Table 2 ).

Single AspergillomaA single aspergilloma (SA) is a fungus ball in the lung city of an otherwise immunocompetent patient. It causes little or no symptoms. Serological or microbiological evidence of the presence of Aspergillus is possible but not obligatory. The city and the fungal ball remain unchanged over at least 3 months' time ( Table 2 ). The SA results from saprophytic growth in a lung city, that is, without infecting the epithelium and solely benefiting from the nutrients, humidity, and ideal environmental temperature of 37°C. The pathogenesis of SA is characterized by formation of a fungal biofilm, composed of hyphae embedded in an ECM. 19 This incites epithelial low-grade inflammation through mechanical stirring which can occasionally cause life-threatening hemoptysis. 59

Aspergillus NoduleAn Aspergillus nodule is often a post-hoc diagnosis, after resection of one or more nodules (