Estimated reading time: 10 minutes;

Sometimes, the most dangerous number isn’t the one your doctor talks about. While LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) steals the spotlight in most lab reports, it’s not always the best predictor of cardiovascular risk. Hidden in plain sight is a more powerful marker: non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C)—a measure that captures all the cholesterol carried by atherogenic, plaque-building particles, not just LDL. And in many patients, it tells a different—and more alarming—story.

Update Notice:This article was originally published in 2021. It has been fully revised and updated in 2025 to reflect the latest clinical evidence and guidelines on non-HDL cholesterol and remnant lipoproteins.

What Is Non-HDL-Cholesterol?Non-HDL-C is calculated by subtracting HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) from total cholesterol:

Non-HDL-C = Total cholesterol – HDL-C

For example, if your total cholesterol is 220 mg/dL (5.7 mmol/L) and HDL-C is 50 mg/dL (1.3 mmol/L), your non-HDL cholesterol is 170 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L). What remains represents cholesterol in LDL, VLDL, IDL, lipoprotein(a), and remnants—key drivers of plaque buildup.

Lipoproteins and Atherogenic RiskThe word atherogenic refers to the potential of certain substances—like specific lipoproteins—to promote atherosclerosis, the slow buildup of fatty deposits in artery walls. When these deposits grow, they can narrow or block blood flow, setting the stage for heart attacks or strokes.

To understand why non-HDL-C matters, we need to revisit the biology of cholesterol transport. Cholesterol doesn’t float freely in the bloodstream. It’s packaged inside lipoproteins—spherical particles made of lipids and proteins—that shuttle fats to and from tissues. There are several types:

Chylomicrons transport dietary fats but are typically not involved in atherosclerosis.

VLDL (Very Low-Density Lipoprotein) carries triglycerides and cholesterol.

IDL (Intermediate-Density Lipoprotein) is a transitional form between VLDL and LDL.

LDL (Low-Density Lipoprotein) delivers cholesterol to tissues and is highly atherogenic.

Lipoprotein(a) is a genetically determined particle that resembles LDL but includes an additional protein called apolipoprotein(a); it is highly atherogenic and often elevated in people with premature heart disease.

HDL (High-Density Lipoprotein) helps clear cholesterol from the bloodstream, often dubbed “good cholesterol.”

While HDL plays a protective role, the rest—especially LDL, VLDL, IDL, lipoprotein(a), and remnants—can infiltrate artery walls, trigger inflammation, and promote plaque formation. Non-HDL-C captures the cholesterol carried by all these atherogenic lipoproteins.

Remnants are what’s left after VLDL and chylomicrons offload their triglycerides into tissues. These particles shrink in size but become denser and more cholesterol-rich. Because they’re small enough to penetrate arterial walls—yet large enough to carry a harmful cholesterol load—they’re especially dangerous and strongly linked to atherosclerosis.

Why Non-HDL-C Matters Today More Predictive Across PopulationsA 2023 meta-analysis demonstrated that cumulative non-HDL-C exposure over years was associated with significantly increased risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), with hazard ratios rising by 26–91% across durations of 2–6 years.

Another nationwide study of 3.8 million individuals found that high non-HDL-C consistently predicted myocardial infarction and stroke, with stronger associations than LDL-C and sustained across age, sex, diabetes, hypertension, and statin use.

Guides Treatment After Heart AttacksA 2024 study from the Swedish SWEDEHEART registry examined over 56,000 patients who had experienced a myocardial infarction and tracked their outcomes for a median of 5.4 years. Researchers focused on non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C) levels, analyzing how both early reduction (at 2 months) and sustained control (at 1 year) influenced long-term cardiovascular outcomes.

The findings were striking: patients who achieved and maintained low non-HDL-C levels (≤1.9 mmol/L, or ~73 mg/dL) had a 24% lower risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including recurrent MI, stroke, cardiovascular death, or need for revascularization, compared to those with higher levels. Importantly, the benefits remained significant even after adjusting for traditional risk factors, including LDL-C.

This real-world data supports the idea that non-HDL-C is not only a powerful predictor of residual risk but also a practical treatment target. The study reinforces the importance of monitoring and aggressively lowering non-HDL-C—especially in the early months following a heart attack—to improve long-term outcomes.

Outperforms LDL-C in Modern Meta-AnalysesA major analysis published in 2025 looked at results from multiple clinical trials involving different cholesterol-lowering treatments—such as statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors.

The study found that lowering non-HDL cholesterol and ApoB was more closely tied to reducing heart attack and stroke risk than simply lowering LDL cholesterol alone. This was especially true for people on combination therapy, where targeting multiple lipid markers provided greater protection.

The findings support the idea that doctors should look beyond LDL and pay closer attention to non-HDL-C and ApoB when managing cardiovascular risk.

When LDL-C MisleadsEven with optimal LDL-C, residual atherogenic particles may persist.

A 2024 study demonstrates that elevated remnant cholesterol and triglycerides are strongly linked to an increased risk of developing multiple cardiometabolic conditions over time.

In particular, individuals with coronary heart disease were more likely to progress to hing both heart disease and type 2 diabetes when remnant cholesterol and triglycerides were elevated. These findings highlight the importance of monitoring and managing these often-overlooked lipid markers—not just to prevent atherosclerosis, but also to reduce the burden of cardiometabolic multimorbidity, where heart disease and metabolic disorders converge.

A typical example is a patient with metabolic syndrome:

Total cholesterol: 210 mg/dL (5.4 mmol/L) LDL-C: 110 mg/dL (2.8 mmol/L) — appears acceptable. HDL-C: 38 mg/dL (1.0 mmol/L) — low. Triglycerides: 240 mg/dL (2.7 mmol/L) — elevated. Non-HDL-C: 172 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L) — clearly high.On paper, the LDL-C might not raise concern. But the elevated non-HDL-C reflects a blood full of remnant and triglyceride-rich particles that heighten cardiovascular risk.

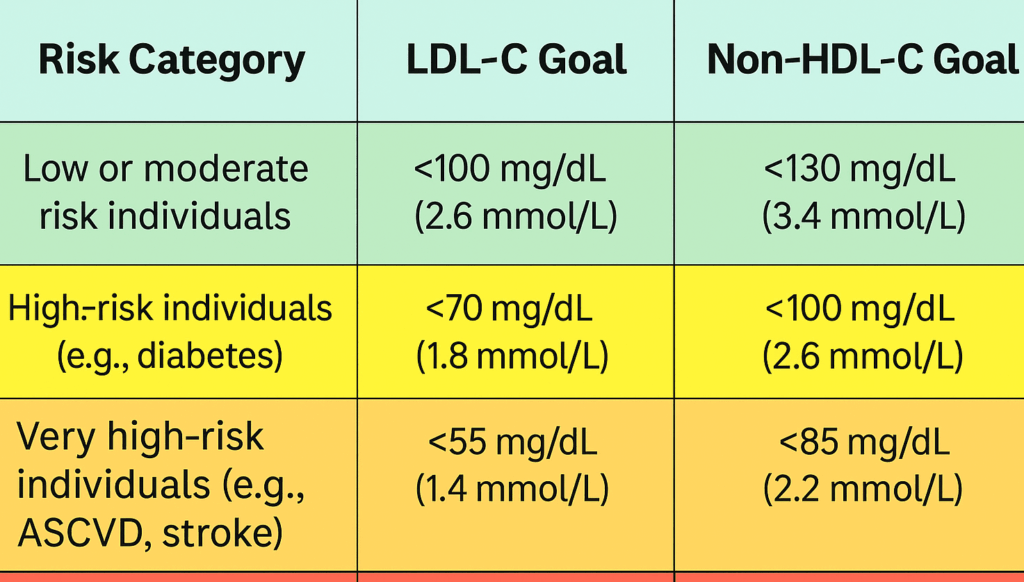

Treatment Targets: How Low Should We Go?Despite its growing clinical relevance, non-HDL-C is often left unflagged unless it exceeds a high threshold—typically around 160 mg/dL (4.1 mmol/L). Yet for many patients, especially those at elevated cardiovascular risk, that’s far too lenient.

Contemporary guidelines suggest that non-HDL-C goals should be set 30 mg/dL (0.8 mmol/L) higher than the corresponding LDL-C target. This adjustment accounts for the atherogenic particles beyond LDL—remnants, VLDL, IDL, and others—that contribute meaningfully to residual risk.

Here’s how current targets are defined by risk category:

Recommended LDL-C and Non-HDL-C Treatment Goals by Risk Category. Targets become progressively lower with increasing cardiovascular risk. Non-HDL-C goals are typically set 30 mg/dL (0.8 mmol/L) above corresponding LDL-C goals to account for all atherogenic particles beyond LDL.

Recommended LDL-C and Non-HDL-C Treatment Goals by Risk Category. Targets become progressively lower with increasing cardiovascular risk. Non-HDL-C goals are typically set 30 mg/dL (0.8 mmol/L) above corresponding LDL-C goals to account for all atherogenic particles beyond LDL.

Put simply: the lower the non-HDL-C, the better—especially for patients with prior events or persistent metabolic risk.

While non-HDL-C gives us a fuller picture than LDL-C, it still doesn’t tell the whole story. To truly understand atherogenic risk, we need to consider the number of lipoprotein particles — and that’s where ApoB comes in.”

Understanding the ApoB – Non-HDL-C RelationshipThere’s a simple but powerful distinction at the heart of lipoprotein science:

ApoB counts particles.

Non-HDL-C measures the cholesterol inside those particles.

Every atherogenic lipoprotein particle — whether it’s an LDL, VLDL, IDL, Lp(a), or chylomicron remnant — carries exactly one ApoB molecule. That makes ApoB a direct measure of particle number, a kind of headcount for the agents of atherosclerosis.

By contrast, non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C) tells us how much cholesterol mass is being carried within those particles. It’s a bulk measurement — useful, but sometimes misleading.

Here’s why the distinction matters:Imagine two people with the same non-HDL-C level. One has many small, cholesterol-poor particles. The other has fewer large, cholesterol-rich ones. Their non-HDL-C is identical — but their ApoB (and risk) is not. The person with more particles (higher ApoB) has greater exposure of the endothelium to atherogenic lipoproteins.

Clinical takeaway:

ApoB is a better marker of atherogenic burden than non-HDL-C, especially in cases of discordance — such as insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome, where particle number and cholesterol content diverge.

But when ApoB isn’t ailable, non-HDL-C is a strong second-best — far better than LDL-C alone.

Putting It Into PracticeNon-HDL-C is not a new test. It’s a reinterpretation of familiar numbers. You don’t need fasting. You don’t need special labs. And it applies whether you’re screening for risk, titrating statins, or chasing residual risk in complex patients.

Here are a few key takeaways for implementation:

Calculate it: Any lipid panel with total cholesterol and HDL-C gives you what you need.

Track trends over time: Persistent elevation of non-HDL-C, even with normal LDL-C, suggests ongoing atherogenic exposure.

Don’t overlook remnant cholesterol: Subtract LDL-C from non-HDL-C. If the remainder is >30 mg/dL (0.8 mmol/L), triglyceride-rich particles may be a problem.

Treat to target: Use statins as first-line agents. Add ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors if needed. Consider omega-3 fatty acids or fibrates when triglycerides are persistently elevated.

How Lifestyle and Exercise Influence Non-HDL-C and RemnantsUnlike LDL-C, which is often the focus of statin therapy, non-HDL cholesterol and remnant cholesterol are highly responsive to lifestyle, particularly diet, weight management, and physical activity. Because these markers include triglyceride-rich particles, such as VLDL and remnants, they’re tightly linked to metabolic health and insulin sensitivity.

Exercise plays a powerful role. Regular aerobic activity—such as brisk walking, cycling, or swimming—can significantly lower triglycerides and improve the clearance of remnant particles. Even moderate-intensity exercise done consistently (150–300 minutes per week) has been shown to reduce VLDL production and enhance lipoprotein lipase activity, which helps break down remnants more effectively.

Diet also matters. Reducing refined carbohydrates, added sugars, and alcohol intake can sharply lower triglyceride levels and remnant cholesterol. Diets rich in unsaturated fats (like olive oil, fatty fish, and nuts), fiber, and lean protein improve lipid metabolism. Weight loss, even as little as 5–10% of body weight, can significantly improve non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C) and triglyceride levels, especially in individuals with insulin resistance or metabolic syndrome.

In sum, non-HDL-C and remnants are modifiable through lifestyle and often respond more readily than LDL-C. That makes them not just powerful risk markers, but also promising treatment targets through everyday interventions.

ConclusionNon-HDL cholesterol is more than a calculation—it’s a lens that lets us see a fuller picture of atherogenic risk. In the statin era, where residual cardiovascular events remain stubbornly high, this marker has become increasingly relevant.

Recent studies from 2023 to 2025 confirm what forward-thinking lipidologists he long suspected: non-HDL-C consistently outperforms LDL-C in predicting cardiovascular events, especially in patients with mixed dyslipidemia or insulin resistance.

If your lipid panel includes total cholesterol and HDL-C, the data is already there. All that’s missing is attention.

It’s time for non-HDL-C to receive the clinical spotlight it deserves.

Related Reading on Doc’s Opinion Atherogenic Dyslipidemia (link) When High LDL Leads to Heart Disease — And When It Doesn’t (link) The 12-Step Biology of Atherosclerosis (link) The Triglyceride/HDL Cholesterol Ratio (link) LDL-C vs. LDL-P: What’s the Difference? (link) What’s the Best Lipid Marker to Predict Risk? (link) Apolipoprotein B and Heart Disease (link) High Triglycerides — And How to Lower Them (link) VLDL, Triglycerides & Remnant Cholesterol (link) HDL Cholesterol — The Good, the Misunderstood (link) 10 Pitfalls of Using LDL-C to Assess Risk (link) LDL Particle Number vs. Size — Made Easy (link) LDL-P (link) The Role of Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) in Atherosclerosis and Heart Disease (link) Metabolic Syndrome and Insulin Resistance (link)Lipoprotein(a): The Overlooked Particle That Most Cholesterol Tests Miss (link)

References Guan XM, Shi HP, Xu S, Chen Y, Zhang RF, Dong YX, Gao LJ, Wu SL, Xia YL. Cumulative non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol burden and risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a prospective community-based study. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 May 18;10:1105342. Link Tran-Duy A, Huynh QL, Phan HT, et al. Non-HDL-cholesterol vs. LDL-cholesterol as predictors of Hansen MK, Mortensen MB, Warnakula Olesen KK, Thrane PG, Maeng M. Non-HDL cholesterol and residual risk of cardiovascular events in patients with ischemic heart disease and well-controlled LDL cholesterol: a cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023 Nov 4;36:100774. Link Schubert J, Leosdottir M, Lindahl B, Westerbergh J, Melhus H, Modica A, Cater N, Brinck J, Ray KK, Hagström E. Intensive early and sustained lowering of non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol after myocardial infarction and prognosis: the SWEDEHEART registry. Eur Heart J. 2024 Oct 14;45(39):4204-4215. Link Katsi, V.; Argyriou, N.; Fragoulis, C.; Tsioufis, K. The Role of Non-HDL Cholesterol and Apolipoprotein B in Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Review. J. Cardiovasc. Dev. Dis. 2025, 12, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcdd12070256. Link Zhao Y, Zhuang Z, Li Y, Xiao W, Song Z, Huang N, Wang W, Dong X, Jia J, Clarke R, Huang T. Elevated blood remnant cholesterol and triglycerides are causally related to the risks of cardiometabolic multimorbidity. Nat Commun. 2024 Mar 19;15(1):2451. Link Share this post: Share on X (Twitter) Share on Facebook Share on LinkedIn Share on Email