Robin Douglas

“Does anyone still believe in the Roman gods?” asked my classmate in our school Latin lesson. It was an odd thing to ask. He was probably just bored of pluperfect verbs and thought that it was worth trying for a digression. Our teacher clearly didn’t know the answer, and ducked the question by asking one of his own: “Did the Romans believe in their gods?” (Answer: Probably, in most cases, although belief wasn’t as big a deal for them as it is for Christians.)

I didn’t know it at the time, but the right answer to the question that my classmate asked in that suburban British classroom 30 years ago was “Yes”. There are large numbers of people today in formerly Christian countries who practise paganism, defined broadly as beliefs and practices that seek to revive the deities, rituals, symbols and religious philosophies of ancient pre-Christian Europe. In England, for example, around 90,000 pagans showed up in the 2021 census, which is generally regarded as an undercount. The total number of modern pagans across the Western world must be in the hundreds of thousands, if not over a million. Most people would regard this as somewhat surprising. How we got to this point is a puzzle which scholars in the small but fascinating field of Pagan Studies he spent the past 20-30 years trying to solve.

Modern pagans from the Ύπατο Συμβούλιο των Ελλήνων Εθνικών (Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes) at a ceremony for the Spring Equinox of 2016 amid the ruins of a temple of Artemis in the Peloponnese, Greece.

Modern pagans from the Ύπατο Συμβούλιο των Ελλήνων Εθνικών (Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes) at a ceremony for the Spring Equinox of 2016 amid the ruins of a temple of Artemis in the Peloponnese, Greece.

The modern pagan revival has its origins in the 18th century. By that time, the Christian religious monopoly in European society had been broken, and alternative ways of seeing and engaging with the world were beginning to emerge. The main alternative to traditional Christianity was Enlightenment thought. The Enlightenment, broadly speaking, was a rationalist, sceptical project: it was essentially secular in nature. Enlightenment philosophers were not necessarily atheists, but they did tend to be uninterested in any religious commitments beyond stripped-down, minimalist forms of monotheism: yes, OK, maybe God exists, but he doesn’t matter very much.

In the 18th and 19th centuries, Christianity and Enlightenment freethinking formed a kind of two-party system. In simplified summary, throughout Europe and the European colonies the same basic choice was on offer: you could stick with the traditional faith of Christ, or you could adopt the semi-respectable alternative of rationalism. To a large extent, we are still offered the same choice today. Yet then, as now, some people were not satisfied with this binary menu of options; they wanted something else entirely. They found institutional Christianity to be authoritarian and repressive; but they were also repelled by the Enlightenment alternative, with its dry intellectualism and spiritual emptiness.

The famous, heily allegorical frontispiece to the final volume of the central publication of the Enlightenment, L’Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751-72), engred by Bonenture-Louis Prévost after an original 1764 drawing by Charles-Nicolas Cochin.

The famous, heily allegorical frontispiece to the final volume of the central publication of the Enlightenment, L’Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers (1751-72), engred by Bonenture-Louis Prévost after an original 1764 drawing by Charles-Nicolas Cochin.

The alternative that these dissidents alighted on was revived paganism. They looked into the Greek and Latin texts that had been hammered into them at school and found a conception of the divine that was pluralistic and non-exclusive, together with an ethics that seemed to be free from the strictures of Christian moralism. These pioneers of the pagan revival tended to be arty types, and some of them are very well known.

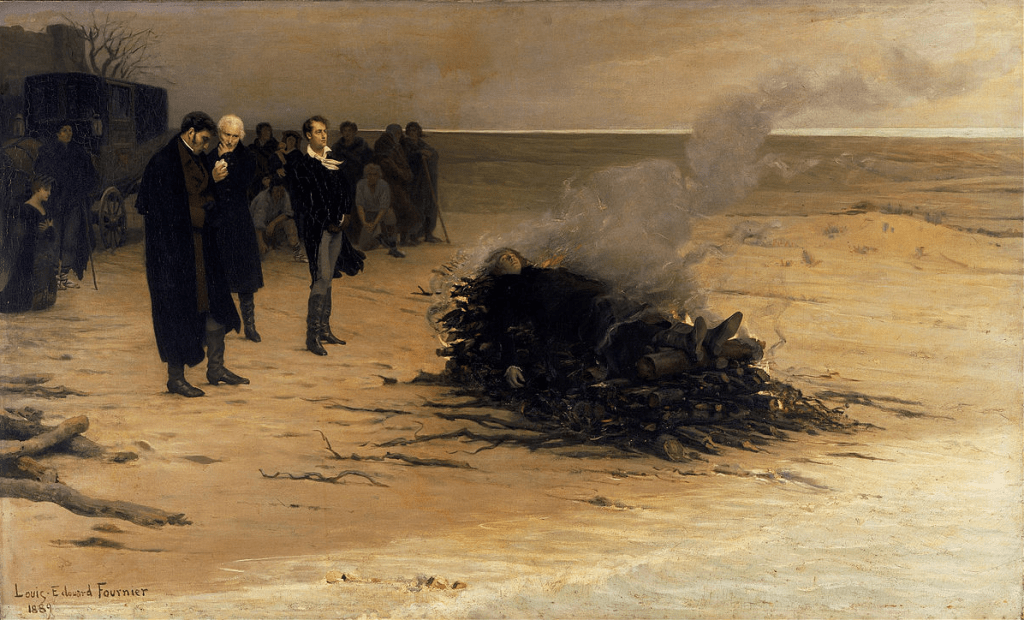

Among the most important early pagan revivalists were the A-list poets Percy Shelley and John Keats, together with other members of the literary circles around them, such as Leigh Hunt, Thomas Jefferson Hogg and Thomas Love Peacock. When Shelley suddenly died in 1822, in a shipwreck off the coast of Tuscany, his friends carried out the first pagan funeral rites that the Italian peninsula had seen since the conversion of the Roman Empire. The activities of Shelley and his friends were only the start.

The funeral of Shelley, Louis-Édouard Fournier, 1889 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK).

The funeral of Shelley, Louis-Édouard Fournier, 1889 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK).

The later Romantic poets George Meredith and Algernon Swinburne wrote luxuriant verse about Mother Earth, Persephone and Isis. The young Arthur Rimbaud wrote a piece entitled “Credo in Unam”, “I believe in one [Goddess]”, intending it to serve as a replacement non-Christian creed for poets. Even Oscar Wilde and the children’s author Kenneth Grahame got in on the act: Wilde wrote a poem summoning Pan to Victorian London, and the same Greek god made a surprise guest appearance in The Wind in the Willows.

These engagements with paganism did not necessarily involve a deep pagan religiosity. In many cases, they amounted to experiments – flirtations, even – with classical polytheism rather than a project of religious revival in the strong sense. But then Christians and rationalists often had uneven and fluctuating relationships with their own systems, and the pagan current grew stronger and more committed over time. By 1890, middle-class Londoners who had an interest in such things could join the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn and participate in rites in which they venerated Jesus Christ alongside Ancient Egyptian and Greek deities.

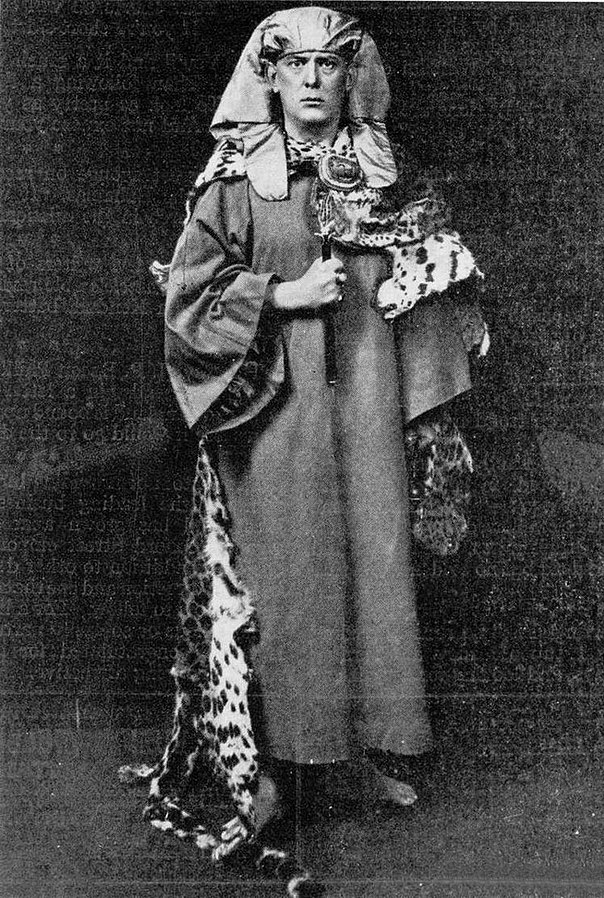

Aleister Crowley in ceremonial dress for a ritual of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, c.1910.

Aleister Crowley in ceremonial dress for a ritual of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, c.1910.

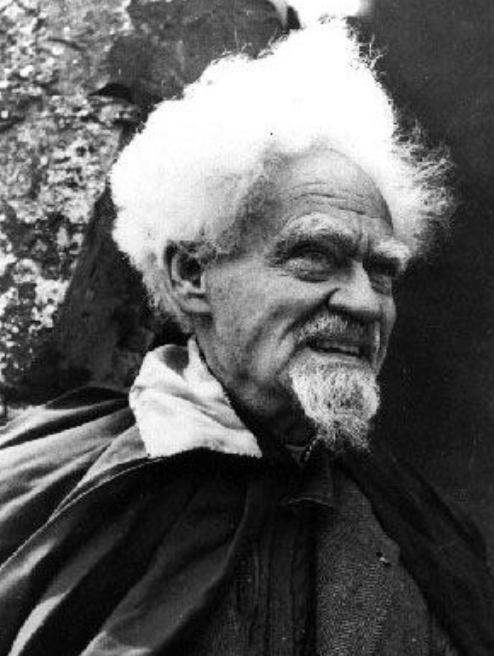

The 20th century saw a further unfolding of the pagan revival movement. Pagan ideas and practices attracted all kinds of people, from the notorious occultist Aleister Crowley – who claimed that he had a cosmic mission “to restore paganism in a purer form” – to the Christian mystic Dion Fortune – who celebrated rites for Isis and Pan in a former church in Belgria. By the time the Second World War ended, the conditions were in place for a full-scale revival of paganism as a mass movement. The best known and most influential manifestation of this was the witch religion known as Wicca, which was popularised in the 1950s by a former colonial official by the name of Gerald Gardner.

Other revival efforts also emerged, and by the 1990s there were multiple pagan persuasions of all kinds across the Western world. These ranged from groups influenced by Crowley and Gardner to more or less detailed attempts to reanimate the pre-Christian traditions of Ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, the Celtic countries and the Germanic tribes. These expressions of revived paganism continue to flourish today: the modern pagan scene is more vibrant than ever, with a large presence on social media and in other online venues.

Gerald Gardner, photographed in the 1950s.

Gerald Gardner, photographed in the 1950s.

So much for the modern pagan revival. Yet such revivalism did not appear for the first time in the modern age. On the contrary, it has been a consistent and recurring feature of European history since the rise of Christianity in Late Antiquity. People he been trying to revive paganism ever since it was replaced. This can be attributed to the enormous reservoir of ideas, stories, images and symbols that go to make up the Classical heritage in Western culture. The materials for reviving ancient pagan religion he always been there. So it is no surprise that people he repeatedly felt the urge to take them up and breathe new life into them. There was, indeed, a strand in conservative Christianity that felt that Classical pagan literature was dangerous precisely because it had this potential.

In the early 16th century, a bishop condemned the newly founded St Paul’s School in London as a “house of idolatry” because it taught the pagan poets. It was always possible to move on from reading about the gods to worshipping them; from making statues of them to performing rites to them; and from reading the ideas of pagan philosophers to believing in them. The surprising thing is not that so many people went on that journey, but that more did not.

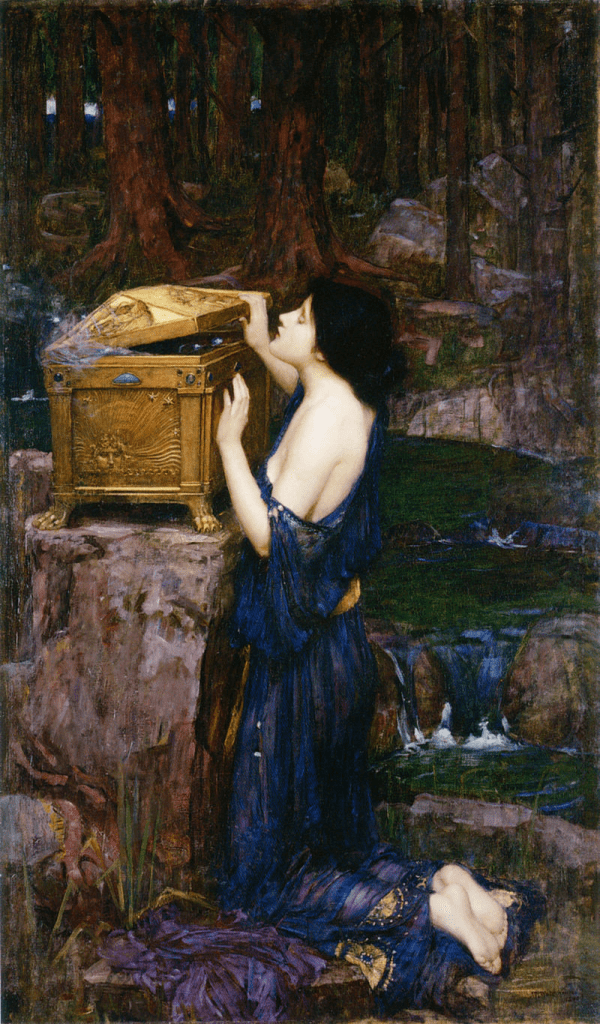

Pandora, John William Waterhouse, 1896 (priv. coll.).

Pandora, John William Waterhouse, 1896 (priv. coll.).

The first pagan revivalist – and still the best known – was the Emperor Julian, a strange young philosopher-general who ruled the Roman Empire from AD 361 to 363. By this time, Christianity had become established as the religion of the imperial house and of much of the Empire’s population – a process that famously started with the conversion of the Emperor Constantine in 312.

By the 360s, the old pagan cults were decidedly on the back foot, although they must still he had the allegiance of at least a significant minority of people, including prominent figures such as the orator Symmachus. The onward march of Christianity was repugnant to Julian. He sought to redirect the course of history and to replace the worship of “the Nazarene” with a form of paganism derived from the philosophy of Plato. More specifically, Julian was a follower of the Neo-Platonist tradition, a form of Platonist thought which had developed in the 3rd century.

Julian the Apostate presiding over a conference of sectarians, Edward Armitage, 1875 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK).

Julian the Apostate presiding over a conference of sectarians, Edward Armitage, 1875 (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool, UK).

Neo-Platonism taught that the cosmos, including the gods, emanated from a single ultimate divine source. (The original Neo-Platonists were pagans, but, interestingly, a Christian version of the school grew up in which the ultimate divinity was equated with the God of the Bible.) At any rate, Julian acted as a kind of pagan pope, sending out pontifical letters to his clerics, preaching a gospel of Neo-Platonism, and seeking to build up a new pagan priesthood to rival the Christian one. But it was too little, too late.

Julian’s project was cut short when he was killed in battle with the Persians; it is far from clear, however, whether he would he been more successful if he had lived any longer. Paganism took a long time to die – and some Christians, such as the scholar Macrobius, continued to harbour a nostalgia for the old pagan world – but by Julian’s time the tipping point had probably been reached.

Cameo of an emperor (possibly Julian) performing a sacrifice to a goddess (possibly Hope), 2nd to 4th cent. AD (National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy).

Cameo of an emperor (possibly Julian) performing a sacrifice to a goddess (possibly Hope), 2nd to 4th cent. AD (National Archaeological Museum, Florence, Italy).

Other pagan revivals inspired by the Platonist philosophical tradition followed, after the ancient world had passed away and the Roman Empire had evolved into the profoundly Christian Byzantine Empire. For example, there was Michael Psellus in the 11th century, a politician and former monk who had a sideline in pagan philosophy and magic. His pupil, John Italus, followed in his footsteps: John’s ideas are still publicly condemned in the liturgy of the Orthodox Church every Lent. A little later, there was an imperial official and diplomat by the name of Georgios Gemistos Plethon, who predicted in the 1430s that in a few years the entire world would become pagan. He attempted to help this development on its way by formulating a whole pagan religio-philosophical system, while also finding time to invent nationalism and socialism.

When the Byzantine Empire fell, these paganising ideas migrated to Western Europe. In Renaissance Italy, contemporary writers and thinkers were obsessed with the Classical heritage, and this inevitably led some towards pagan revivalism. The Platonist philosophers Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola sought to combine paganism with Catholicism, and with surprising success.

Gemistos Plethon is the bearded figure at the centre of this image in the dark-blue cap striped with gold; from the Procession of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli, 1459 (Magi Chapel, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence, Italy).

Gemistos Plethon is the bearded figure at the centre of this image in the dark-blue cap striped with gold; from the Procession of the Magi by Benozzo Gozzoli, 1459 (Magi Chapel, Palazzo Medici Riccardi, Florence, Italy).

It is worth noting in this connection how pagan revivalists from Julian onwards he often tended to be people with philosophical interests, and in particular how many of them he been followers of the Neo-Platonist tradition. The Platonist philosophical inheritance has provided a large part of the intellectual fuel for pagan revivals over the centuries. Notably, it helped to kick off the modern revival in the 18th century through the writings of the English pagan thinker Thomas Taylor, who influenced the network of writers around Shelley and Keats whom we mentioned earlier.

Nevertheless, even in the Renaissance, pagan activity was not confined to philosophical and intellectual circles. Sigismondo Malatesta, who was the warlord of Rimini and something of a practical man, had a local church restructured into a kind of quasi-pagan edifice. The pope took this badly, describing it as a “temple for demon-worshipping infidels”. Pagan sacrifices were also reported in Italy and France in the 1520s and 30s.

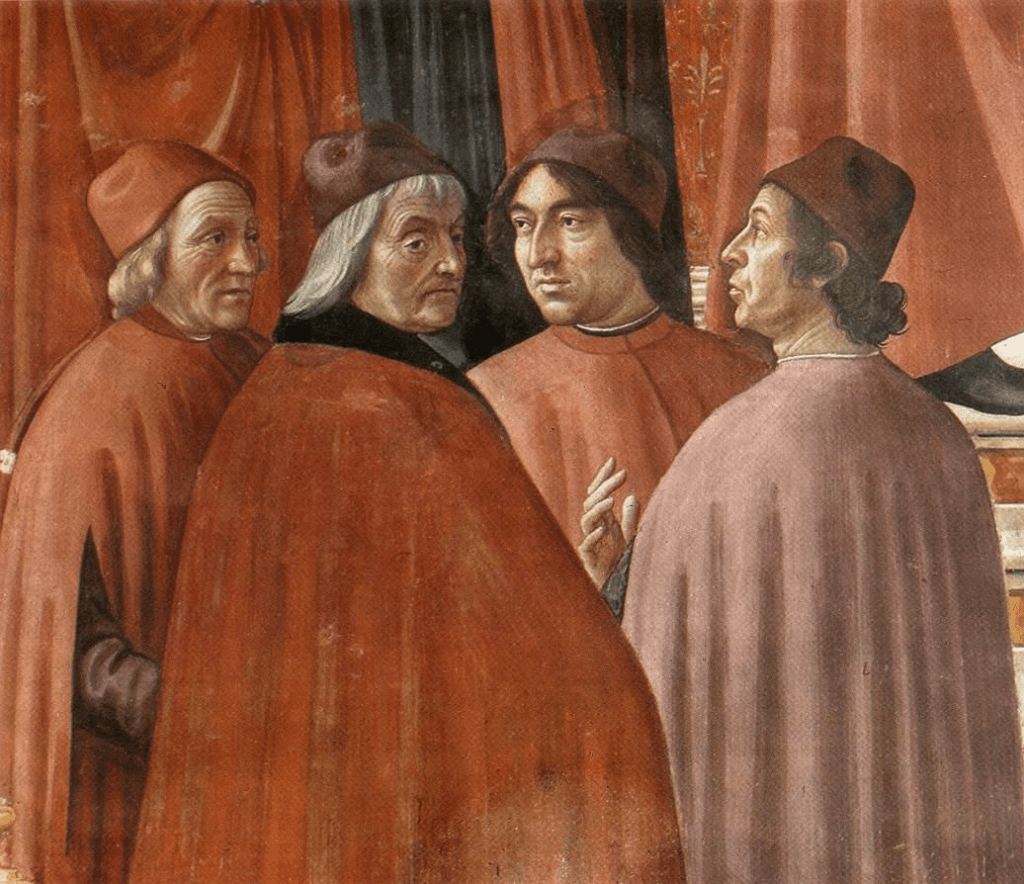

Intellectuals at Lorenzo the Magnificent’s court in 15th-century Florence flirting with paganism: (left to right) Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, Politian and Demetrios Chalcondyles. Detail from a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio of the angel appearing to Zacharias in the Tornabuoni Chapel, 1486/90 (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy).

Intellectuals at Lorenzo the Magnificent’s court in 15th-century Florence flirting with paganism: (left to right) Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino, Politian and Demetrios Chalcondyles. Detail from a fresco by Domenico Ghirlandaio of the angel appearing to Zacharias in the Tornabuoni Chapel, 1486/90 (Santa Maria Novella, Florence, Italy).

The enterprise of reviving paganism is – obviously – not without its critics. Some he said that the whole business is essentially inauthentic. This criticism began to be raised by conservative Christian writers back in the 19th century. It was popularised by the Catholic polemicist G.K. Chesterton, and it has become something of a cliché: modern pagans aren’t really pagan. They are identikit Western liberals, posting about Hekate and Aphrodite on their iPhones as they order incense and crystals from Amazon.

On this view, modern paganism is an individual lifestyle choice rather than the lived religion of an organic community. Even the more conservative practitioners can’t seriously claim to be leading the religious life of an Athenian sle-girl or a Roman peasant farmer – nor would they wish to do so. To take one notable example, very few modern pagan revivalists carry out animal sacrifice, an act that was central to classical religiosity.

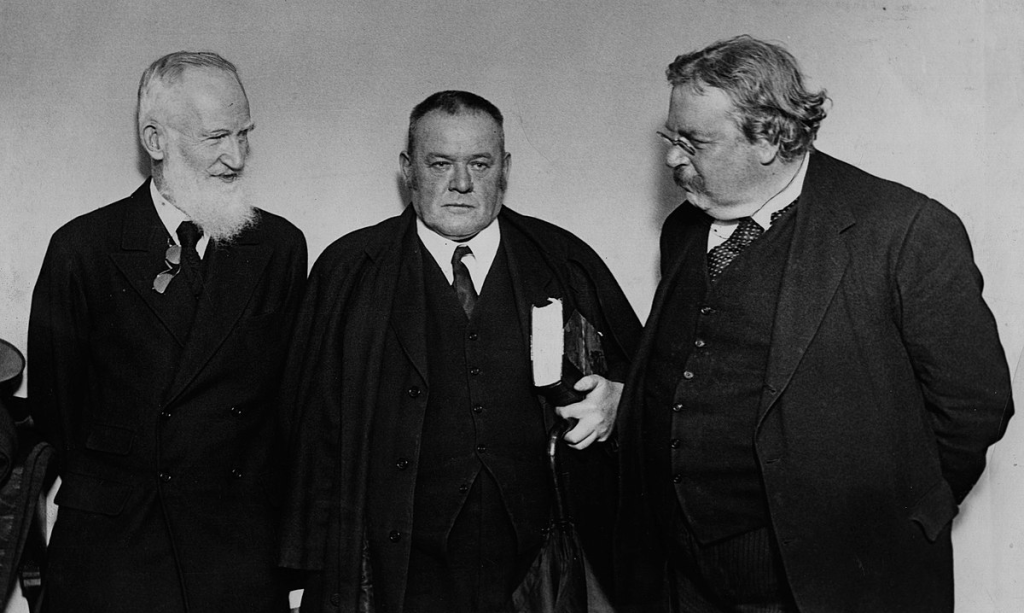

Three great polemicists, photographed in 1927: George Bernard Shaw, Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton.

Three great polemicists, photographed in 1927: George Bernard Shaw, Hilaire Belloc and G. K. Chesterton.

Yet this critique misses the mark. Authenticity is an essentially invalid notion here. Nobody’s religion is pure or unchanging. Christianity itself has historically borrowed from paganism, particularly in its older, pre-Reformation varieties. Indeed, the 16th-century Reformers looked at the galaxy of saints and angels in medieval Catholicism – not to mention the incense, holy water, miraculous images and sacramental rituals – and declared that the whole popish system was just rebranded Roman paganism. Some fundamentalist Protestants still say as much today.

Moreover, no religious movement is ever unchanging. Modern paganism is modern in the same sense that Christianity, Hinduism, Judaism, Buddhism and Islam are all being perpetually reinvented by their adherents in response to evolving modernity. Even fundamentalist anti-modern sects are a response to modernity; and attempts to return to an original ancient purity – for example, in radical Protestantism or Salafi Islam – are doomed to fail, often quite nastily. The erage pagan coven member in Birmingham today is likely to he more liberal views than people in the time of Augustus Caesar; but the same is probably true of the local Anglican vicar. What is more, we should take care not to exaggerate how dominant the modern element in modern paganism is. After all, modern pagans do venerate ancient gods under the inspiration of ancient mythological and philosophical texts, using rituals with ancient components.

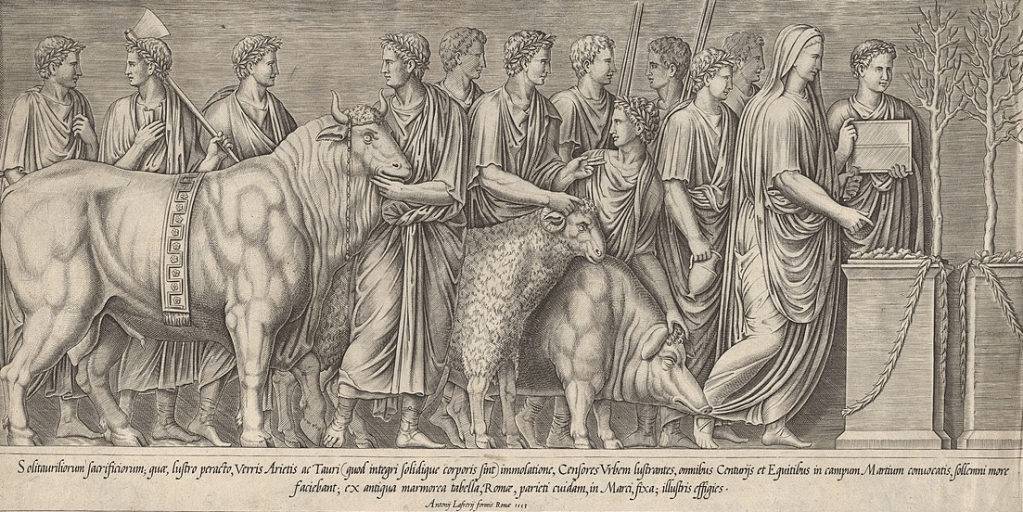

Engring of a pagan sacrifice copied from an ancient bas-relief in Rome; engred by Nicolas Béatrizet and published by Antonio Lafreri, 1553.

Engring of a pagan sacrifice copied from an ancient bas-relief in Rome; engred by Nicolas Béatrizet and published by Antonio Lafreri, 1553.

It is sometimes said that paganism springs eternal in the human breast. On this view, it is a kind of Ur-religion: a spontaneous engagement with plural manifestations of a divinity which is inherent in the natural world; a way of being religious that comes from a time before dogmas, scriptures and clerical hierarchies.

This claim may or may not be true. But paganism has certainly proved to be, if not an eternal element of Western culture, at least a highly durable one. For most people today, it is a dead part of the remote past, whether it is seen as a damnable error that was slain by the cross of Christ or a superstition that has been banished by the lights of science and reason. But yet it keeps on rematerialising. For something that is supposed to be dead, it is remarkably reluctant to lie down.

Robin Douglas is a writer based in London who specialises in the history of pagan, esoteric and other minority religious movements. His academic background is in Classics, and he has a PhD in History from the University of Cambridge. He has recently published a short book, Paganism Persisting, co-written with the historian Francis Young, to investigate the phenomenon of pagan revivals through European history.

Further Reading

Ronald Hutton, The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft (Oxford UP, 1999). A magisterial history of the modern pagan revival.

Joscelyn Godwin, The Pagan Dream of the Renaissance (Thames & Hudson, London, 2002). A treatment of pagan themes in Renaissance culture.

Niketas Siniossoglou, Radical Platonism in Byzantium: Illumination and Utopia in Gemistos Plethon (Cambridge UP, 2011).An academic investigation of revivals of Platonist paganism in the Byzantine empire.

Adrian Murdoch, The Last Pagan: Julian the Apostate and the Death of the Ancient World (Sutton, Stroud, 2003). A popular biography of the Emperor Julian.

Suzanne L. Barnett, Romantic Paganism: The Politics of Ecstasy in the Shelley Circle (Palgre Macmillan, London, 2017). An exploration of the philo-pagan sentiments of the writers around Shelley.

Share this article via: Click to share on X (Opens in new window) X Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window) Facebook